Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

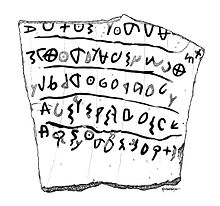

[8][9][10] Like the Phoenician alphabet, it is a slight regional variant and an immediate continuation of the Proto-Canaanite script, which was used throughout Canaan in the Late Bronze Age.

The so-called Ophel inscription is of a similar age, but difficult to interpret, and may be classified as either Proto-Canaanite or as Paleo-Hebrew.

[14] From the 8th century onward, Hebrew epigraphy becomes more common, showing the gradual spread of literacy among the people of the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah; the oldest portions of the Hebrew Bible, although transmitted via the recension of the Second Temple period, are also dated to the 8th century BCE.

The aversion of the lapidary script may indicate that the custom of erecting stelae by the kings and offering votive inscriptions to the deity was not widespread in Israel.

Even the engraved inscriptions from the 8th century exhibit elements of the cursive style, such as the shading, which is a natural feature of pen-and-ink writing.

A slightly earlier (circa 620 BCE) but similar script is found on an ostracon excavated at Mesad Hashavyahu, containing a petition for redress of grievances (an appeal by a field worker to the fortress's governor regarding the confiscation of his cloak, which the writer considers to have been unjust).

Beginning from the 5th century BCE onward, the Aramaic language and script became an official means of communication.

It is found in certain texts of the Torah among the Dead Sea Scrolls, dated to the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE: manuscripts 4Q12, 6Q1: Genesis.

[24] The vast majority of the Hasmonean coinage, as well as the coins of the First Jewish–Roman War and Bar Kokhba's revolt, bears Paleo-Hebrew legends.

[26][28][29] According to both opinions, Ezra the Scribe (c. 500 BCE) introduced, or reintroduced the Assyrian script to be used as the primary alphabet for the Hebrew language.

[26] This third opinion was accepted by some early Jewish scholars,[31] and rejected by others, partially because it was permitted to write the Torah in Greek.

[32] Use of Proto-Hebrew in modern Israel is negligible, but it is found occasionally in nostalgic or pseudo-archaic examples, e.g. on the ₪1 coin (𐤉𐤄𐤃 "Judea")[33] and in the logo of the Israeli town Nahariyah (Deuteronomy 33:24 𐤁𐤓𐤅𐤊 𐤌𐤁𐤍𐤉𐤌 𐤀𐤔𐤓 "Let Asher be blessed with children").

In 2019, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) unearthed a 2,600-year-old seal impression, while conducting excavations at the City of David, containing Paleo-Hebrew script, and which is thought to have belonged to a certain "Nathan-Melech," an official in King Josiah's court.

The names are applied depending on the language of the inscription, or if that cannot be determined, of the coastal (Phoenician) vs. highland (Hebrew) association (c.f.