Palaeography

First, since the style of an alphabet, grapheme or sign system set within a register in each given dialect and language has evolved constantly, it is necessary to know how to decipher its individual substantive, occurrence make-up and constituency.

Most likely as a consequence of phonetic changes in North Semitic languages, the Aramaeans reused certain letters in the alphabet to represent long vowels.

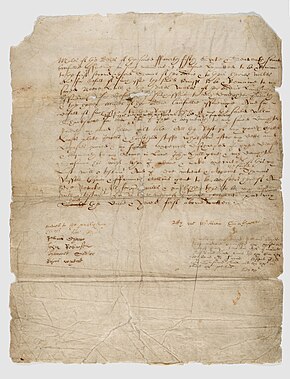

Aramaic papyri have been found in large numbers in Egypt, especially at Elephantine—among them are official and private documents of the Jewish military settlement in 5 BC.

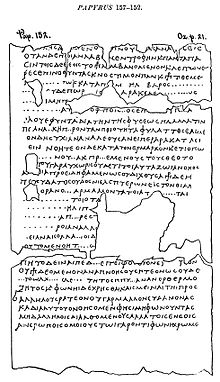

Written with more ease and elegance, it shows little trace of any development towards a truly cursive style; the letters are not linked, and though the uncial ⟨c⟩ is used throughout, ⟨E⟩ and ⟨Ω⟩ have the capital forms.

Some literary papyri, like the roll containing Aristotle's Constitution of Athens, were written in cursive hands, and, conversely, the book-hand was occasionally used for documents.

In the more formal types the letters stand rather stiffly upright, often without the linking strokes, and are more uniform in size; in the more cursive they are apt to be packed closely together.

This, which can be traced back at least the late 2nd century, has a square, rather heavy appearance; the letters, of uniform size, stand upright, and thick and thin strokes are well distinguished.

A general progress towards a florid and sprawling hand is easily recognisable, but a consistent and deliberate style was hardly evolved before the 5th century, from which unfortunately few dated documents have survived.

By the 6th century, alike in vellum and in papyrus manuscripts, the heaviness had become very marked, though the hand still retained, in its best examples, a handsome appearance; but after this it steadily deteriorated, becoming ever more mechanical and artificial.

The hand, which is often singularly ugly[citation needed], passed through various modifications, now sloping, now upright, though it is not certain that these variations were really successive rather than concurrent.

[24] In its earliest examples it is upright and exact but lacks flexibility; accents are small, breathings square in formation, and in general only such ligatures are used as involve no change in the shape of letters.

Their use was established by the beginning of the Roman period, but was sporadic in papyri, where they were used as an aid to understanding, and therefore more frequently in poetry than prose, and in lyrical oftener than in other verse.

Punctuation was effected in early papyri, literary and documentary, by spaces, reinforced in the book-hand by the paragraphos, a horizontal stroke under the beginning of the line.

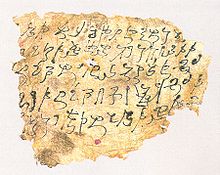

[25] In the new paradigm, Indian alphabetic writing, called Brahmi, was discontinuous with earlier, undeciphered, glyphs, and was invented specifically by King Ashoka for application in his royal edicts 250 BC.

From the 8th century, Siddhamatrika developed into the Śāradā script in Kashmir and Punjab, into Proto-Bengali or Gaudi in Bengal and Orissa, and into Nagari in other parts of north India.

[29] The earliest attested form of writing in South India is represented by inscriptions found in caves, associated with the Chalukya and Chera dynasties.

The difference in this case is determined by the subject matter of the text; the writing used for books (scriptura libraria) is in all periods quite distinct from that used for letters and documents (epistolaris, diplomatica).

[32] In the 19th century such scholars as Wilhelm Wattenbach, Leopold Delisle and Ludwig Traube contributed greatly to making palaeography independent from diplomatic.

[34] Later, the characters of the cursive type were progressively eliminated from formal inscriptions, and capital writing reached its perfection in the Augustan Age.

In the earliest specimens of writing on wax, plaster or papyrus, there appears a tendency to represent several straight strokes by a single curve.

Nevertheless, in spite of a close resemblance which betrays their common origin, these hands are specifically different, perhaps because the Roman cursive was developed by each nation in accordance with its artistic tradition.

[49] In Italy, after the close of the Roman and Byzantine periods, the writing is known as Lombardic, a generic term which comprises several local varieties.

In the 9th century, it was introduced in Dalmatia by the Benedictine monks and developed there, as in Apulia, on the basis of the archetype, culminating in a rounded Beneventana known as the Bari type.

Copyists of books used a cursive similar to that found in documents, except that the strokes are thicker, the forms more regular, and the heads and tails shorter.

Although Italy's dominance as a centre of manuscript production began to decline, especially after the Gothic War (535–554) and the invasions by the Lombards, its manuscripts—and more important, the scripts in which they were written—were distributed across Europe.

This is due to the confusion which prevailed before the Carolingian period in the libraria in France, Italy and Germany as a result of the competition between the cursive and the set hands.

Its place of origin is also uncertain: Rome, the Palatine school, Tours, Reims, Metz, Saint-Denis and Corbie have been suggested, but no agreement has been reached.

This style remained predominant, with some regional variants, until the 15th century, when the Renaissance humanistic scripts revived a version of Carolingian minuscule.

In Petrarch's compact book hand, the wider leading and reduced compression and round curves are early manifestations of the reaction against the crabbed Gothic secretarial minuscule we know today as "blackletter".

The Florentine bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci recalled later in the century that Poggio had been a very fine calligrapher of lettera antica and had transcribed texts to support himself—presumably, as Martin Davies points out—[80] before he went to Rome in 1403 to begin his career in the papal curia.