Panic of 1907

The primary causes of the run included a retraction of market liquidity by a number of New York City banks and a loss of confidence among depositors, exacerbated by unregulated side bets at bucket shops.

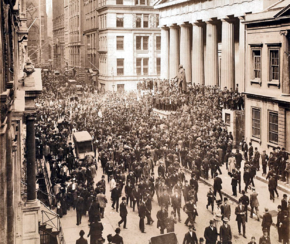

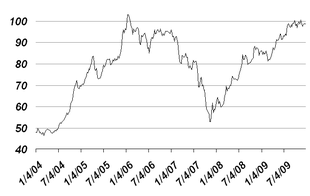

The panic then extended across the nation as vast numbers of people withdrew deposits from their regional banks, causing the 8th-largest decline in U.S. stock market history.

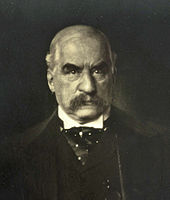

[3] The panic might have deepened if not for the intervention of financier J. P. Morgan,[4] who pledged large sums of his own money and convinced other New York bankers to do the same to shore up the banking system.

That highlighted the limitations of the US Independent Treasury system, which managed the nation's money supply but was unable to inject sufficient liquidity back into the market.

Collapse of TC&I's stock price was averted by an emergency takeover by Morgan's U.S. Steel Corporation, a move approved by the trust-busting President Theodore Roosevelt.

The following year, Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, a leading Republican, established and chaired a commission to investigate the crisis and propose future solutions, which led to the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

[8][9] A further stress on the money supply occurred in late 1906, when the Bank of England raised its interest rates, partly in response to UK insurance companies paying out so much to US policyholders, and more funds remained in London than expected.

The Hepburn Act, which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates, became law in July 1906.

[16] On July 27, The Commercial & Financial Chronicle noted that "the market keeps unstable ... no sooner are these signs of new life in evidence than something like a suggestion of a new outflow of gold to Paris sends a tremble all through the list, and the gain in values and hope is gone".

[19] Augustus' brother, Otto, devised the scheme to corner United Copper, believing that the Heinze family already controlled a majority of the company.

As a result of United Copper's collapse, the State Savings Bank of Butte Montana (owned by F. Augustus Heinze) announced its insolvency.

The Mercantile had enough capital to withstand a few days of withdrawals, but depositors began to pull cash from the banks of the Heinzes' associate Charles W. Morse.

The following morning, the library of Morgan's brownstone at Madison Avenue and 36th St. had become a revolving door of New York City bank and trust company presidents arriving to share information about (and seek help surviving) the impending crisis.

After an overnight audit of the Trust Company of America showed the institution to be sound, on Wednesday afternoon Morgan declared, "This is the place to stop the trouble, then.

To instill public confidence, Rockefeller phoned Melville Stone, the manager of the Associated Press, and told him that he would pledge half of his wealth to maintain U.S.

[39] Despite the infusion of cash, the banks of New York were reluctant to make the short-term loans they typically provided to facilitate daily stock trades.

Public confidence needed to be restored, and on Friday evening the bankers formed two committees—one to persuade the clergy to calm their congregations on Sunday, and a second to explain to the press the various aspects of the financial rescue package.

[44] In an attempt to gather confidence, the Treasury Secretary Cortelyou agreed that if he returned to Washington it would send a signal to Wall Street that the worst had passed.

[45][46] To ensure a free flow of funds on Monday, the New York Clearing House issued $100 million in loan certificates to be traded between banks to settle balances, allowing them to retain cash reserves for depositors.

[47] Reassured both by the clergy and the newspapers, and with bank balance sheets flush with cash, a sense of order returned to New York that Monday.

There Morgan told his counselors that he would agree to help shore up Moore & Schley only if the trust companies would work together to bail out their weakest brethren.

As discussion ensued, the bankers realized that Morgan had locked them in the library and pocketed the key to force a solution,[53] the sort of strong-arm tactic he had been known to use in the past.

With less than an hour before the Stock Exchange opened, Roosevelt and Secretary of State Elihu Root began to review the proposed takeover and appreciate the crash likely to ensue if the merger was not approved.

[57][58] Roosevelt relented; he later recalled of the meeting, "It was necessary for me to decide on the instant before the Stock Exchange opened, for the situation in New York was such that any hour might be vital.

[62] The frequency of crises and the severity of the 1907 panic added to concern about the outsized role of J.P. Morgan and renewed impetus toward a national debate on reform.

Early in 1907, banker Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. warned in a speech to the New York Chamber of Commerce that "unless we have a central bank with adequate control of credit resources, this country is going to undergo the most severe and far reaching money panic in its history".

[66] In 1908: Frank A. Vanderlip led a U.S. business delegation to Japan to meet with Japanese financial leaders including Taka Kawada, Shibusawa Eiichi and his son Shibusawa Masao, also founding members of Mitsui & Co., Takuma Dan & Takamine Mitsui with the goal allying with Japan to resolve the Panic of 1907 and the unstable U.S. stock market.

[67] Aldrich convened a secret conference with a number of the nation's leading financiers at the Jekyll Island Club, off the coast of Georgia, to discuss monetary policy and the banking system in November 1910.

[72] Although Morgan lost $21 million in the panic, and the significance of the role he played in staving off worse disaster is undisputed, he also became the focus of intense scrutiny and criticism.

He became ill in February and died on March 31, 1913, nine months before the Federal Reserve officially replaced the "money trust" as lender of last resort.