Paris in the Middle Ages

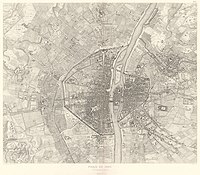

In the 10th century Paris was a provincial cathedral city of little political or economic significance, but under the kings of the Capetian dynasty who ruled France between 987 and 1328, it developed into an important commercial and religious center and the seat of the royal administration of the country.

Due to its position at the confluence of the Seine and the rivers Oise, Marne and Yerres, the city was abundantly supplied with food from the surrounding region, which was rich in grain fields and vineyards.

During the Merovingian era of Frankish rule (481–751 AD), the Île de la Cité had ramparts, and some of the monasteries and churches were protected by wooden stockades walls, but the residents of the Left and Right Banks were largely undefended.

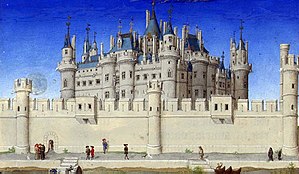

[13] The palace complex included the residence of the king, with a private chapel, or oratory; a building for the law courts; a large hall for ceremonies; and a donjon, or tower, which was still standing in the mid-19th century.

The presence of the nobles in Paris created a large market for luxury goods, such as furs, silks, armor and weapons, causing the merchants of the Right Bank to thrive.

[14] Between 1361 and 1364, Charles V, distrustful of the turbulent Parisians and offended by the foul air and smells of the medieval city, decided to move his residence permanently from the Île de la Cité to a safer and healthier location.

The Catholic Church played a prominent role in the city throughout the Middle Ages; it owned a large part of the land and wealth, was the creator of the University of Paris and was closely linked to the king and the government.

Clerics also made up a significant part of the population; in 1300, the Bishop of Paris was assisted by 51 chanoines (canons), and each of the thirty-three parish churches had its own curé (curate), vicar, and chaplains.

[19] The first monasteries appeared in Paris during the Merovingian Dynasty (481–731 AD) and were mostly located around the Mountain of Sainte-Geneviève on the Left Bank, where the old Roman city of Lutetia was situated.

[20] In the later Middle Ages, important positions in the church were given more and more often to members of the aristocracy of wealthy families who had provided services to the Court; abbots were assured of a large income.

One of the greatest benefits was to receive one of the twenty-seven houses that surrounded the cloister of Notre Dame, located northeast of the cathedral at the end of the Île de la Cité.

The Franciscan Order came in 1217–1219 and established chapters at Saint Denis, on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, and, with the support of King Louis IX, at Saint-Germain des Prés.

[21] Another important religious order arrived in Paris in the mid-12th century: the Knights Templar, who established their headquarters at the Old Temple on the Right Bank next to the Seine near the churches of Saint-Gervais and Saint-Jean-en-Grève.

As the century advanced, the intellectual center moved from Notre Dame to the Left Bank, where the monasteries, which were independent of the Bishop of Paris, began to establish their own schools.

Dissection of corpses was forbidden in the medical school long after it became common practice at other universities, and unorthodox ideas were regularly condemned by the faculty; individuals viewed as heretics were punished.

In 1121, during the reign of Louis VI, the king accorded to the league of boatmen of Paris a fee of sixty centimes for each boatload of wine that arrived in the city during the harvest.

After the Grève, the second-largest port was by the church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerois, where ships unloaded fish from the coast, wood from the forests along the Aisne and Oise Rivers, hay from the Valley of the Seine, and cider from Normandy.

In January 1357, Étienne Marcel led a merchants' revolt in a bid to curb the power of the monarchy and obtain privileges for the city and the Estates General, which had met for the first time in Paris in 1347.

This night watch was insufficient to maintain security in such a large city, so a second force of guardians was formed whose members were permanently stationed at key points around Paris.

It was largely the result of the strict code of honor in effect in the Middle Ages; an insult, such as throwing a person's hat in the mud, required a response, which often led to a death.

Beginning in about 1314, a large gibet was built on a hill outside of Paris, near the modern Parc des Buttes Chaumont, where the bodies of executed criminals were displayed.

[47] Royal justice was administered by the Provost of Paris, who had his office and his own prison in the Grand Châtelet fortress on the Right Bank at the end of the Pont de la Cité.

The diets of the rich Parisians in the late Middle Ages were exotic and varied; they were supplied with olive oil and citrus fruits from the Mediterranean Basin, cinnamon from Egypt, and saffron and sugar from Italy and Spain.

[53] Official news and announcements were made to the Parisians by the guild of town criers, who were first chartered by the king, and then put under the authority of the League of River Merchants.

A special event in the royal family – a coronation, birth, baptism, marriage, or simply the entry of the king or queen into the city – was usually the occasion for a public celebration.

This style, later designated Gothic, was copied by other Paris churches: the Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs, Saint-Pierre de Montmartre, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and quickly spread to England and Germany.

[57] Beginning in the reign of Charles VI (1380–1422), French noblemen and wealthy merchants began building large townhouses, mostly in the Le Marais neighborhood that were usually surrounded by walls and often had gardens.

Among the most celebrated artists were the Limbourg Brothers, who produced the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, and Jean Fouquet, who illustrated the history of France for his royal patrons.

The king and royal government returned to the city, and the powers of the provost of the Paris merchants were drastically reduced; until the French Revolution, it became only a symbolic office.

The corporations of artisans also took sides; the butchers, one of the largest and most powerful guilds, gave their support to the Burgundians, and were rewarded with patronage, influence and large casks of Burgundy wine.