Pauli exclusion principle

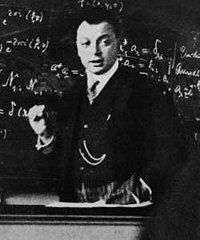

This principle was formulated by Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli in 1925 for electrons, and later extended to all fermions with his spin–statistics theorem of 1940.

Any number of identical bosons can occupy the same quantum state, such as photons produced by a laser, or atoms found in a Bose–Einstein condensate.

A more rigorous statement is: under the exchange of two identical particles, the total (many-particle) wave function is antisymmetric for fermions and symmetric for bosons.

So, if hypothetically two fermions were in the same state—for example, in the same atom in the same orbital with the same spin—then interchanging them would change nothing and the total wave function would be unchanged.

Additionally, baryons such as protons and neutrons (subatomic particles composed from three quarks) and some atoms (such as helium-3) are fermions, and are therefore described by the Pauli exclusion principle as well.

[2]: 123–125 The Pauli exclusion principle underpins many properties of everyday matter, from its large-scale stability to the chemical behavior of atoms.

In contrast, particles with integer spin (bosons) have symmetric wave functions and may share the same quantum states.

[3] In 1919 chemist Irving Langmuir suggested that the periodic table could be explained if the electrons in an atom were connected or clustered in some manner.

[4] In 1922, Niels Bohr updated his model of the atom by assuming that certain numbers of electrons (for example 2, 8 and 18) corresponded to stable "closed shells".

For this purpose he introduced a new two-valued quantum number, identified by Samuel Goudsmit and George Uhlenbeck as electron spin.

[6][7] In his Nobel lecture, Pauli clarified the importance of quantum state symmetry to the exclusion principle:[8] Among the different classes of symmetry, the most important ones (which moreover for two particles are the only ones) are the symmetrical class, in which the wave function does not change its value when the space and spin coordinates of two particles are permuted, and the antisymmetrical class, in which for such a permutation the wave function changes its sign...[The antisymmetrical class is] the correct and general wave mechanical formulation of the exclusion principle.The Pauli exclusion principle with a single-valued many-particle wavefunction is equivalent to requiring the wavefunction to be antisymmetric with respect to exchange.

Any two-particle state can be represented as a superposition (i.e. sum) of these basis vectors: where each A(x, y) is a (complex) scalar coefficient.

In relativistic quantum field theory, the Pauli principle follows from applying a rotation operator in imaginary time to particles of half-integer spin.

The reason for this is that, in one dimension, the exchange of particles requires that they pass through each other; for infinitely strong repulsion this cannot happen.

Later, K. Deilamian et al.[12] used an atomic beam spectrometer to search for the paronic state 1s2s 1S0 calculated by Drake.

In conductors and semiconductors, there are very large numbers of molecular orbitals which effectively form a continuous band structure of energy levels.

[13]: 133–147 Many mechanical, electrical, magnetic, optical and chemical properties of solids are the direct consequence of Pauli exclusion.

[14] However, stability of large systems with many electrons and many nucleons is a different question, and requires the Pauli exclusion principle.

[15] It has been shown that the Pauli exclusion principle is responsible for the fact that ordinary bulk matter is stable and occupies volume.

This suggestion was first made in 1931 by Paul Ehrenfest, who pointed out that the electrons of each atom cannot all fall into the lowest-energy orbital and must occupy successively larger shells.

[16] The first rigorous proof was provided in 1967 by Freeman Dyson and Andrew Lenard (de), who considered the balance of attractive (electron–nuclear) and repulsive (electron–electron and nuclear–nuclear) forces and showed that ordinary matter would collapse and occupy a much smaller volume without the Pauli principle.

They provided a lower bound on the quantum energy in terms of the Thomas-Fermi model, which is stable due to a theorem of Teller.

The consequence of the Pauli principle here is that electrons of the same spin are kept apart by a repulsive exchange interaction, which is a short-range effect, acting simultaneously with the long-range electrostatic or Coulombic force.

This effect is partly responsible for the everyday observation in the macroscopic world that two solid objects cannot be in the same place at the same time.

Dyson and Lenard did not consider the extreme magnetic or gravitational forces that occur in some astronomical objects.

In 1995 Elliott Lieb and coworkers showed that the Pauli principle still leads to stability in intense magnetic fields such as in neutron stars, although at a much higher density than in ordinary matter.

[19] It is a consequence of general relativity that, in sufficiently intense gravitational fields, matter collapses to form a black hole.

Astronomy provides a spectacular demonstration of the effect of the Pauli principle, in the form of white dwarf and neutron stars.

In white dwarfs, which do not undergo nuclear fusion, an opposing force to gravity is provided by electron degeneracy pressure.

However, even this enormous rigidity can be overcome by the gravitational field of a neutron star mass exceeding the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit, leading to the formation of a black hole.