Spin quantum number

[5] The (total) spin quantum number has only one value for every elementary particle.

Some introductory chemistry textbooks describe ms as the spin quantum number,[6][7] and s is not mentioned since its value 1/2 is a fixed property of the electron; some even use the variable s in place of ms.[5] The two spin quantum numbers

However, this simplistic picture was quickly realized to be physically unrealistic, because it would require the electrons to rotate faster than the speed of light.

[10] Irving Langmuir had explained in his 1919 paper regarding electrons in their shells, "Rydberg has pointed out that these numbers are obtained from the series

configuration was adopted by Edmund Stoner, in October 1924 in his paper 'The Distribution of Electrons Among Atomic Levels' published in the Philosophical Magazine.

The qualitative success of the Sommerfeld quantum number scheme failed to explain the Zeeman effect in weak magnetic field strengths, the anomalous Zeeman effect.

In December 1924, Wolfgang Pauli showed that the core electron angular momentum was not related to the effect as had previously been assumed.

[12]: 563 Rather he proposed that only the outer "light" electrons determined the angular momentum and he hypothesized that this required a fourth quantum number with a two-valuedness.

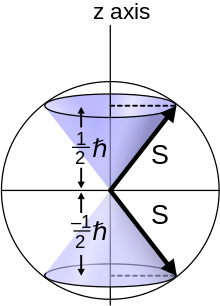

A spin- 1 /2 particle is characterized by an angular momentum quantum number for spin s = 1 /2.

The hydrogen spectrum fine structure is observed as a doublet corresponding to two possibilities for the z-component of the angular momentum, where for any given direction z:

The spin property of an electron would give rise to magnetic moment, which was a requisite for the fourth quantum number.

The nuclear spin I is a fixed property of each nucleus and may be either an integer or a half-integer.

Odd mass number nuclei have half-integer spins, such as 3/ 2 for 7Li, 1 /2 for 13C and 5/ 2 for 17O, usually corresponding to the angular momentum of the last nucleon added.

Odd-odd nuclei with odd numbers of both protons and neutrons have integer spins, such as 3 for 10B, and 1 for 14N.

When lines of the hydrogen spectrum are examined at very high resolution, they are found to be closely spaced doublets.

This splitting is called fine structure, and was one of the first experimental evidences for electron spin.

The direct observation of the electron's intrinsic angular momentum was achieved in the Stern–Gerlach experiment.

The theory of spatial quantization of the spin moment of the momentum of electrons of atoms situated in the magnetic field needed to be proved experimentally.

In 1922 (two years before the theoretical description of the spin was created) Otto Stern and Walter Gerlach observed it in the experiment they conducted.

The laws of classical physics predict that the collection of condensed silver atoms on the plate should form a thin solid line in the same shape as the original beam.

However, the in-homogeneous magnetic field caused the beam to split in two separate directions, creating two lines on the metallic plate.

But in the valence shell of silver atoms, there is a single electron whose spin remains unbalanced.

The atom would then be pulled toward or away from the stronger magnetic field a specific amount, depending on the value of the valence electron's spin.

Later scientists conducted experiments using other atoms that have only one electron in their valence shell: (copper, gold, sodium, potassium).

The atomic nucleus also may have spin, but protons and neutrons are much heavier than electrons (about 1836 times), and the magnetic dipole moment is inversely proportional to the mass.

For atoms or molecules with an unpaired electron, transitions in a magnetic field can also be observed in which only the spin quantum number changes, without change in the electron orbital or the other quantum numbers.

This means that it is impossible to know two coordinates of the spin at the same time because of the restriction of the uncertainty principle.

In 1928, Paul Dirac developed a relativistic wave equation, now termed the Dirac equation, which predicted the spin magnetic moment correctly, and at the same time treated the electron as a point-like particle.

Solving the Dirac equation for the energy levels of an electron in the hydrogen atom, all four quantum numbers including s occurred naturally and agreed well with experiment.

This is equal to the number of different possible values of the total (orbital plus spin) angular momentum J for a given (L, S) combination, provided that S ≤ L (the typical case).