Electronegativity

The loosely defined term electropositivity is the opposite of electronegativity: it characterizes an element's tendency to donate valence electrons.

The term "electronegativity" was introduced by Jöns Jacob Berzelius in 1811,[2] though the concept was known before that and was studied by many chemists including Avogadro.

[2] In spite of its long history, an accurate scale of electronegativity was not developed until 1932, when Linus Pauling proposed an electronegativity scale which depends on bond energies, as a development of valence bond theory.

When other methods of calculation are used, it is conventional (although not obligatory) to quote the results on a scale that covers the same range of numerical values: this is known as an electronegativity in Pauling units.

[6] It is to be expected that the electronegativity of an element will vary with its chemical environment,[7] but it is usually considered to be a transferable property, that is to say that similar values will be valid in a variety of situations.

where the dissociation energies, Ed, of the A–B, A–A and B–B bonds are expressed in electronvolts, the factor (eV)−1⁄2 being included to ensure a dimensionless result.

Hydrogen was chosen as the reference, as it forms covalent bonds with a large variety of elements: its electronegativity was fixed first[3] at 2.1, later revised[8] to 2.20.

However, in principle, since the same electronegativities should be obtained for any two bonding compounds, the data are in fact overdetermined, and the signs are unique once a reference point has been fixed (usually, for H or F).

The essential point of Pauling electronegativity is that there is an underlying, quite accurate, semi-empirical formula for dissociation energies, namely:

The square root of this excess energy, Pauling notes, is approximately additive, and hence one can introduce the electronegativity.

In more complex compounds, there is an additional error since electronegativity depends on the molecular environment of an atom.

Such a formula for estimating energy typically has a relative error on the order of 10% but can be used to get a rough qualitative idea and understanding of a molecule.

See also: Electronegativities of the elements (data page)There are no reliable sources for Pm, Eu and Yb other than the range of 1.1–1.2; see Pauling, Linus (1960).

As this definition is not dependent on an arbitrary relative scale, it has also been termed absolute electronegativity,[11] with the units of kilojoules per mole or electronvolts.

[14] By inserting the energetic definitions of the ionization potential and electron affinity into the Mulliken electronegativity, it is possible to show that the Mulliken chemical potential is a finite difference approximation of the electronic energy with respect to the number of electrons., i.e.,

The effective nuclear charge, Zeff, experienced by valence electrons can be estimated using Slater's rules, while the surface area of an atom in a molecule can be taken to be proportional to the square of the covalent radius, rcov.

[18] Sanderson's model has also been used to calculate molecular geometry, s-electron energy, NMR spin-spin coupling constants and other parameters for organic compounds.

[22] Perhaps the simplest definition of electronegativity is that of Leland C. Allen, who has proposed that it is related to the average energy of the valence electrons in a free atom,[23][24][25]

[26] However, it is not clear what should be considered to be valence electrons for the d- and f-block elements, which leads to an ambiguity for their electronegativities calculated by the Allen method.

The most obvious application of electronegativities is in the discussion of bond polarity, for which the concept was introduced by Pauling.

Pauling proposed an equation to relate the "ionic character" of a bond to the difference in electronegativity of the two atoms,[5] although this has fallen somewhat into disuse.

Several correlations have been shown between infrared stretching frequencies of certain bonds and the electronegativities of the atoms involved:[27] however, this is not surprising as such stretching frequencies depend in part on bond strength, which enters into the calculation of Pauling electronegativities.

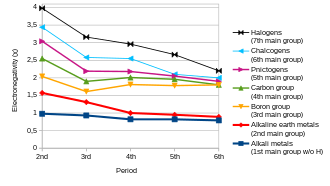

[1][5] In general, electronegativity increases on passing from left to right along a period and decreases on descending a group.

Gallium and germanium have higher electronegativities than aluminium and silicon, respectively, because of the d-block contraction.

In inorganic chemistry, it is common to consider a single value of electronegativity to be valid for most "normal" situations.

[30] Allred used the Pauling method to calculate separate electronegativities for different oxidation states of the handful of elements (including tin and lead) for which sufficient data were available.

[8] However, for most elements, there are not enough different covalent compounds for which bond dissociation energies are known to make this approach feasible.

At the same time, the positive partial charge on the hydrogen increases with a higher oxidation state.

Electropositivity is a measure of an element's ability to donate electrons, and therefore form positive ions; thus, it is antipode to electronegativity.

This is because they have a single electron in their outer shell and, as this is relatively far from the nucleus of the atom, it is easily lost; in other words, these metals have low ionization energies.