Pernambucan revolt

Other important reasons for the revolt include: the ongoing struggle for the independence of Spanish colonies all over in South America; the independence of the United States; the generally liberal ideas that came through all of Brazil the century before, including many French Philosophers, such as Charles Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau; the actions of secret societies, which insisted on the liberation of the colony; the development of a distinct culture in Pernambuco.

[4] The revolt can be traced from the presence of the Portuguese royal family in Brazil, which mostly benefited the plantation owners, merchants and bureaucrats of the Central and Southern regions of the country.

[5] The historical analyst, Maria Odila Silva Dias, remarked that "in order to cover the costs of installing public works and civil servants, taxes on the export of sugar, tobacco and leather were increased, creating a series of troubles that directly affected the capitanias of the North, which the Court did not hesitate to burden with the violence of recruitment and with contributions to cover the expenses of war in the kingdom, in Guiana and in the Prata region.

"[5] In the peak of the revolt, one finds that the strongest Pernambucan patriots marked their identity in several methods – including drinking aguardente instead of wine and host made of wheat.

Argentine historian Emilio Ocampo investigated the life of Carlos María de Alvear, and found British documents about a Bonapartist plot in Pernambuco to free Napoleón Bonaparte, and take him to some strategic location in South America, in order to create a new Napoleonic Empire.

When Napoleon's four veterans, Count Pontelécoulant, Colonel Latapie, orderly Artong and soldier Roulet, arrived in Brazil long after the revolution had ended, they were arrested before disembarking.

These revolutionaries anticipated the danger to the movement, which began after the Pernambucan capitan, José de Barros Lima (nicknamed the Crowned Lion), killed the Portuguese officer assigned to arrest him.

The revolt extended to Ceará, Paraíba and to Rio Grande do Norte, but was only able to survive two months before Recife was surrounded by sea and land by troops of the Portuguese monarch.

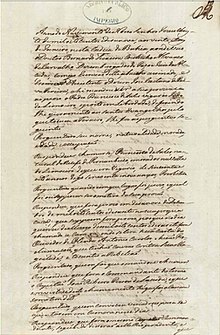

The design was copied in watercolor by the Rio de Janeiro artist Antônio Álvares—a painting that still existed when Ribeiro was writing in the 1930s—essentially the same as the modern state flag with the field dark blue over white, a single star above the rainbow.