Persian miniature

Normally all the pigments used are mineral-based ones which keep their bright colours very well if kept in proper conditions, the main exception being silver, mostly used to depict water, which will oxidize to a rough-edged black over time.

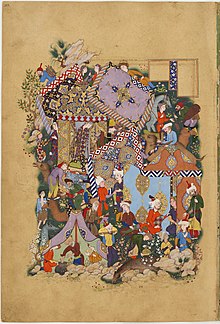

Animals, especially the horses that very often appear, are mostly shown sideways on; even the love-stories that constitute much of the classic material illustrated are conducted largely in the saddle, as far as the prince-protagonist is concerned.

[7] The earliest miniatures appeared unframed horizontally across the page in the middle of text, following Byzantine and Arabic precedents, but in the 14th century the vertical format was introduced, perhaps influenced by Chinese scroll-paintings.

There are often panels of text or captions inside the picture area, which is enclosed in a frame, eventually of several ruled lines with a broader band of gold or colour.

Album miniatures usually showed a few figures on a larger scale, with less attention to the background, and tended to become drawings with some tints of coloured wash, rather than fully painted.

In the example at right the clothes are fully painted, and the background uses the gold grisaille style earlier reserved for marginal decoration, as in the miniature at the head of the article.

After a brief and high-flown introduction, "Petition from the most humble servants of the royal library, whose eyes are as expectant of the dust from the hooves of the regal steed as the ears of those who fast are for the cry of Allahu akbar ..." it continues with very businesslike and detailed notes on what each of some twenty-five named artists, scribes and craftsmen has been up to over a period of perhaps a week: "Amir Khalil has finished the waves in two sea-scenes of the Gulistan and will begin to apply colour.

[20] The ancient Persian religion of Manichaeism made considerable use of images; not only was the founding prophet Mani (c.216–276) a professional artist, at least according to later Islamic tradition, but one of the sacred books of the religion, the Arzhang, was illustrated by the prophet himself, whose illustrations (probably essentially cosmological diagrams rather than images with figures) were regarded as part of the sacred material and always copied with the text.

[29] The Ilkhanids continued to migrate between summer and winter quarters, which together with other travels for war, hunting and administration, made the portable form of the illustrated book the most suitable vehicle for painting, as it also was for mobile European medieval rulers.

[32] It was only in the 14th century that the practice began of commissioning illustrated copies of classic works of Persian poetry, above all the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi (940-1020) and the Khamsa of Nizami, which were to contain many of the finest miniatures.

[34] Many of the best miniatures from early manuscripts were removed from their books in later centuries and transferred to albums, several of which are now in Istanbul; this complicates tracing the art history of the period.

[39] But a famous unfinished miniature showing Rustam asleep, while his horse Rakhsh fights off a lion, was probably made for this manuscript, but was never finished and bound in, perhaps because its vigorous Tabriz style did not please Tahmasp.

[40] Before Chinese influence was introduced, figures were tied to the ground line and included "backgrounds of solid color", or in "clear accordance with indigenous artistic traditions".

[46] Sultan Mohammed, Mir Sayyid Ali, and Aqa Mirak, were leading painters of the next generation, the Safavid culmination of the classic style, whose attributed works are found together in several manuscripts.

[48] In the 19th century, the miniatures of Abu'l-Hasan Khan Gaffari (Sani ol molk), active in Qajar Persia, showed originality, naturalism, and technical perfection.

The first was the transfer of elements and techniques of Chinese art to Iran, and the second was the establishment of a form of collective artistic education in workshops and royal libraries.

One of the notable events of this period was the creation of a cultural complex near Tabriz, known as Rab'-e Rashidi, by the order of Rashid al-Din Fazlullah Hamadani, the vizier of Ghazan Khan.

The illustrations of Shirazi books were simple and reminiscent of Seljuk-era manuscripts, characterized by flat and vibrant colors, large figures, and shallow spaces, evoking the ancient traditions of Iranian art.

During Baysonqor Mirza's reign, the workshop of the royal court in Herat became a melting pot of artistic influences from Shiraz, Tabriz, and even Chinese painting traditions.

Despite the upheavals in Herat after Shah Rukh's death until the reign of Hussain Bayqara, independent artworks from artists such as Maulana Vali Allah and Mansur were produced.

The establishment of Sultan Husayn Bayqara's rule and the presence of his minister, Mir Ali-Shir Nava'i, marked a splendid era for art in Iran.

During this period, alongside the traditional masters who continued the Baysonqori style, a new generation of talented and innovative artists emerged, introducing new experiences to Persian painting.

Calligraphic elements gained particular importance in the composition, and fixed rules for arranging and formatting texts were established, which became inseparable from the Shiraz style until the late 10th century AH.

The general rule was to place two or four inscriptions at the top and bottom of the image, creating a symmetrical and geometric structure within the artwork, with significant subjects often appearing in the central section and beneath the horizon line.

One notable work produced in Safavid Herat is the "Zafarnama" (Book of Victory), characterized by intricate compositions, diverse colors, and strong design, displaying elements of Behzad's style.

Overall, in Mashhad, we encounter new characteristics, including emphasis on color through white spots, dominance of soft and curvilinear lines, presence of ancient trees, fragmented rocks, and slender figures with long necks and round faces.

Architecture, textiles, carpets, and ceramics of this era had numerous enthusiastic admirers, yet, with a fair critique, one can find a decline in vitality and creativity in almost all the arts of this period.

The first trend continued until the end of Moin Mosavar's life, while the inclination towards naturalism grew and became more formalized, marking a new beginning in the Iranian painting style.

[50] In their rationale for inscription on the list, the nominators highlighted that "The patterns of the miniature represent beliefs, worldviews and lifestyles in a pictorial fashion and also gained a new character through the Islamic influence.

In all cases, it is a traditional craft typically transmitted through mentor-apprentice relationships (non-formal education) and considered as an integral part of each society's social and cultural identity".