Philistines

During the Late Bronze Age collapse, an apparent confederation of seafarers known as the Sea Peoples are recorded as attacking ancient Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean civilizations.

Following the Sea Peoples' defeat, Ramesses III allegedly relocated a number of the pwrꜣsꜣtj to southern Canaan, as recorded in an inscription from his funerary temple in Medinet Habu,[20] and the Great Harris Papyrus.

[21][22] Though archaeological investigation has been unable to correlate any such settlement existing during this time period,[23][24][25] this, coupled with the name Peleset/Pulasti and the peoples' supposed Aegean origins, has led many scholars to identify the pwrꜣsꜣtj with the Philistines.

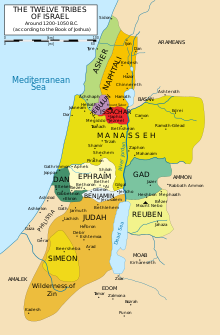

[27] There is little evidence that the Sea Peoples forcefully injected themselves into the southern Levant; and the cities which would become the core of Philistine territory, such as Ashdod,[28] Ashkelon,[29] Gath,[30] and Ekron,[31] show nearly no signs of an intervening event marked by destruction.

[39] Ten years later, Egypt once again incited its neighbors to rebel against Assyria, resulting in Ashkelon, Ekron, Judah, and Sidon revolting against Sargon's son and successor, Sennacherib.

Sennacherib crushed the revolt, defeated the Egyptians, and destroyed much of the cities in southern Aramea, Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah, and entered the northern Sinai, though he was unable to capture the Judahite capital, Jerusalem, instead forcing it to pay tribute.

[40] In 604/603 BC, following a Philistine revolt, Nebuchadnezzar II, the king of Babylon, took over and destroyed Askhelon, Gaza, Aphek, and Ekron, which is proven by archaeological evidence and contemporary sources.

[12] Babylonian ration lists dating back to the early 6th century BC, which mention the offspring of Aga, the ultimate ruler of Ashkelon, provide clues to the eventual fate of the Philistines.

This differentiation was also held by the authors of the Septuagint (LXX), who translated (rather than transliterated) its base text as "foreigners" (Koinē Greek: ἀλλόφυλοι, romanized: allóphylloi, lit.

[49][59] Based on the LXX's regular translation as "foreigners", Robert Drews states that the term "Philistines" means simply "non-Israelites of the Promised Land" when used in the context of Samson, Saul and David.

[88] This view is based largely upon the fact that archaeologists, when digging up strata dated to the Philistine time-period in the coastal plains and in adjacent areas, have found similarities in material culture (figurines, pottery, fire-stands, etc.)

[89][90][91] A minority, dissenting, claims that the similarities in material culture are only the result of acculturation, during their entire 575 years of existence among Canaanite (Phoenician), Israelite, and perhaps other seafaring peoples.

[105] In 2003, a statue of a king named Taita bearing inscriptions in Luwian was discovered during excavations conducted by German archaeologist Kay Kohlmeyer in the Citadel of Aleppo.

[106] The new readings of Anatolian hieroglyphs proposed by the Hittitologists Elisabeth Rieken and Ilya Yakubovich were conducive to the conclusion that the country ruled by Taita was called Palistin.

[100] Based on the Peleset inscriptions, it has been suggested that the Casluhite[citation needed] Philistines formed part of the conjectured "Sea Peoples" who repeatedly attacked Egypt during the later Nineteenth Dynasty.

[124] The inscriptions at Medinet Habu consist of images depicting a coalition of Sea Peoples, among them the Peleset, who are said in the accompanying text to have been defeated by Ramesses III during his Year 8 campaign.

They were comprehensively defeated by Ramesses III, who fought them in "Djahy" (the eastern Mediterranean coast) and at "the mouths of the rivers" (the Nile Delta), recording his victories in a series of inscriptions in his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu.

A separate relief on one of the bases of the Osiris pillars with an accompanying hieroglyphic text clearly identifying the person depicted as a captive Peleset chief is of a bearded man without headdress.

[127] The Harris Papyrus, which was found in a tomb at Medinet Habu, also recalls Ramesses III's battles with the Sea Peoples, declaring that the Peleset were "reduced to ashes."

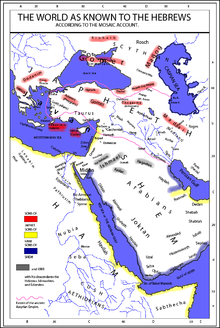

The sequence in question has been translated as: "Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gaza, Assyria, Shubaru [...] Sherden, Tjekker, Peleset, Khurma [...]" Scholars have advanced the possibility that the other Sea Peoples mentioned were connected to these cities in some way as well.

[127] Many scholars have interpreted the ceramic and technological evidence attested to by archaeology as being associated with the Philistine advent in the area as strongly suggestive that they formed part of a large scale immigration to southern Canaan,[1][3][130] probably from Anatolia and Cyprus, in the 12th century BC.

However, for many years scholars such as Gloria London, John Brug, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Helga Weippert, and Edward Noort, among others, have noted the "difficulty of associating pots with people", proposing alternative suggestions such as potters following their markets or technology transfer, and emphasize the continuities with the local world in the material remains of the coastal area identified with "Philistines", rather than the differences emerging from the presence of Cypriote and/or Aegean/ Mycenaean influences.

[142] In the Middle Bronze Age, coastal plains in the southern Levant economically prospered due to long-distance exchange with the Aegean, Cypriot and Egyptian civilizations.

[146] The Leon Levy Expedition, which has been going on since 1985, helped break down some of the previous assumptions that the Philistines were uncultured people by having evidence of perfume near the bodies in order for the deceased to smell it in the afterlife.

[149] The finding fits with an understanding of the Philistines as an "entangled" or "transcultural" group consisting of peoples of various origins, said Aren Maeir, an archaeologist at Bar-Ilan University in Israel.

[42] There is some limited evidence in favour of the assumption that the Philistines were originally Indo-European-speakers, either from Greece or Luwian speakers from the coast of Asia Minor, on the basis of some Philistine-related words found in the Bible not appearing to be related to other Semitic languages.

[155][156][157] The deities worshipped in the area were Baal, Ashteroth (that is, Astarte), Asherah, and Dagon, whose names or variations thereof had already appeared in the earlier attested Canaanite pantheon.

[158] Beelzebub, a supposed hypostasis of Baal, is described in the Hebrew Bible as the patron deity of Ekron, though no explicit attestation of such a god or his worship has thus far been discovered, and the name Baal-zebub itself may be the result of an intentional distortion by the Israelites.

[159][160][161] Another name, attested on the Ekron Royal Dedicatory Inscription, is PT[-]YH, unique to the Philistine sphere and possibly representing a goddess in their pantheon,[7] though an exact identity has been subject to scholarly debate.

[162] Still, Dagon-worship probably wasn't completely unheard of amongst the Philistines, as multiple mentions of a city known as Beth Dagon in Assyrian, Phoenician, and Egyptian sources may imply the god was venerated in at least some parts of Philistia.