Photography

It is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing (e.g., photolithography), and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a camera during a timed exposure.

[19] He also first understood the relationship between the focal point and the pinhole,[20] and performed early experiments with afterimages, laying the foundations for the invention of photography in the 19th century.

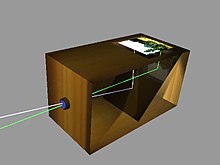

A hole in the cave wall will act as a pinhole camera and project a laterally reversed, upside down image on a piece of paper.

It is a box with a small hole in one side, which allows specific light rays to enter, projecting an inverted image onto a viewing screen or paper.

[23] In June 1802, British inventor Thomas Wedgwood made the first known attempt to capture the image in a camera obscura by means of a light-sensitive substance.

In 1826 he made the View from the Window at Le Gras, the earliest surviving photograph from nature (i.e., of the image of a real-world scene, as formed in a camera obscura by a lens).

[31] Because Niépce's camera photographs required an extremely long exposure (at least eight hours and probably several days), he sought to greatly improve his bitumen process or replace it with one that was more practical.

In partnership with Louis Daguerre, he worked out post-exposure processing methods that produced visually superior results and replaced the bitumen with a more light-sensitive resin, but hours of exposure in the camera were still required.

Daguerre took the earliest confirmed photograph of a person in 1838 while capturing a view of a Paris street: unlike the other pedestrian and horse-drawn traffic on the busy boulevard, which appears deserted, one man having his boots polished stood sufficiently still throughout the several-minutes-long exposure to be visible.

Meanwhile, a British inventor, William Fox Talbot, had succeeded in making crude but reasonably light-fast silver images on paper as early as 1834[32] but had kept his work secret.

After reading about Daguerre's invention in January 1839, Talbot published his hitherto secret method in a paper to the Royal Society[32] and set about improving on it.

In both its original and calotype forms, Talbot's process, unlike Daguerre's, created a translucent negative which could be used to print multiple positive copies; this is the basis of most modern chemical photography up to the present day, as daguerreotypes could only be replicated by rephotographing them with a camera.

He had discovered in 1819 that sodium thiosulphate was a solvent of silver halides, and in 1839 he informed Talbot (and, indirectly, Daguerre) that it could be used to "fix" silver-halide-based photographs and make them completely light-fast.

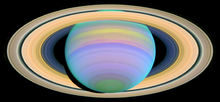

Because of the superior dimensional stability of glass, the use of plates for some scientific applications, such as astrophotography, continued into the 1990s, and in the niche field of laser holography, it has persisted into the 21st century.

Even after color film was readily available, black-and-white photography continued to dominate for decades, due to its lower cost, chemical stability, and its "classic" photographic look.

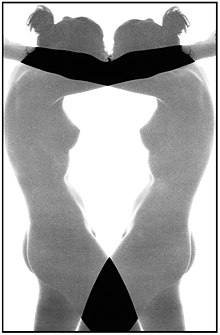

Monochrome printing or electronic display can be used to salvage certain photographs taken in color which are unsatisfactory in their original form; sometimes when presented as black-and-white or single-color-toned images they are found to be more effective.

[43][44] The foundation of virtually all practical color processes, Maxwell's idea was to take three separate black-and-white photographs through red, green and blue filters.

Russian photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii made extensive use of this color separation technique, employing a special camera which successively exposed the three color-filtered images on different parts of an oblong plate.

The dualphoto apparatus can be used to simultaneously capture both the subject and the photographer, or both sides of a geographical place at once, thus adding a supplementary narrative layer to that of a single image.

For instance, a photocopy or xerography machine forms permanent images but uses the transfer of static electrical charges rather than photographic medium, hence the term electrophotography.

[56] Twenty-first century social media and near-ubiquitous camera phones have made photographic and video recording pervasive in everyday life.

Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto's frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne?

[58]On 7 February 2007, Sotheby's London sold the 2001 photograph 99 Cent II Diptychon for an unprecedented $3,346,456 to an anonymous bidder, making it the most expensive at the time.

In parallel to this development, the then largely separate interface between painting and photography was closed in the second half of the 20th century with the chemigram of Pierre Cordier and the chemogram of Josef H.

These works of art were almost simultaneous with the invention of photography by various important artists who characterized Hippolyte Bayard, Thomas Wedgwood, William Henry Fox Talbot in their early stages, and later Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy in the twenties and by the painter in the thirties Edmund Kesting and Christian Schad by draping objects directly onto appropriately sensitized photo paper and using a light source without a camera.

[62] In 1845 Francis Ronalds, the Honorary Director of the Kew Observatory, invented the first successful camera to make continuous recordings of meteorological and geomagnetic parameters.

[71] The camera doesn't rape or even possess, though it may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, at the farthest reach of metaphor, assassinate – all activities that, unlike the sexual push and shove, can be conducted from a distance, and with some detachment.

Many photojournalists have declared they will not crop their pictures or are forbidden from combining elements of multiple photos to make "photomontages", passing them as "real" photographs.

[75] In the UK, a recent law (Counter-Terrorism Act 2008) increases the power of the police to prevent people, even press photographers, from taking pictures in public places.