Photoredox catalysis

Rigid systems, whose geometry is not greatly dependent on oxidation state, therefore experience less vibrational excitation during electron transfer, and have a lower intrinsic barrier.

Since the electron transfer step of the catalytic cycle takes place from the triplet excited state, it competes with phosphorescence as a relaxation pathway.

If the potential applied to the cell is strong enough for electron transfer to occur, the change in concentration of the redox-competent excited state can be measured as an alternating current (AC).

Furthermore, the phase shift of the AC current relative to the intensity of the incident light corresponds to the average lifetime of an excited-state species before it engages in electron transfer.

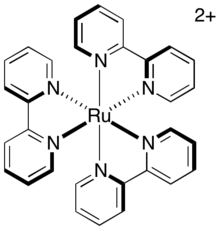

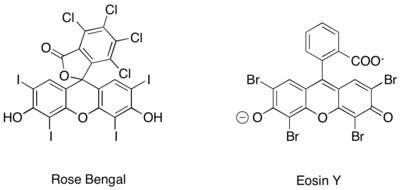

[3] The relative reducing and oxidizing natures of these photocatalysts can be understood by considering the ligands' electronegativity and the catalyst complex's metal center.

If this was the sole factor relevant to redox potentials, then complexes of ruthenium and iridium with the same ligands should be equally powerful photoredox catalysts.

This makes iridium preferred for the development of general organic transformations because the stronger redox potentials of the excited catalyst allows the use of weaker stoichiometric reductants and oxidants or the use of less reactive substrates.

Although photophysical properties such as redox potential, excitation energy, and ligand electronegative have often been considered key parameters for the use and reactivity of these complexes, counter-ion identity has been shown to play a significant role in low-polarity solvents.

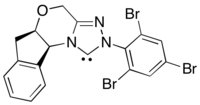

[19] This reaction method sidesteps the problem of poor enantioinduction from chiral photoredox catalysts by moving the source of enantioselectivity to the N-heterocyclic carbene.

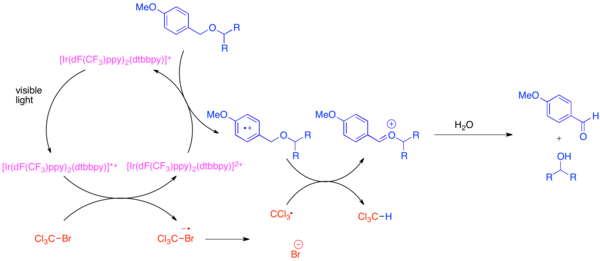

The selective deprotection of PMB ethers can be achieved through the use of bis-(2-(2',4'-difluorophenyl)-5-trifluoromethylpyridine)-(4,4'-ditertbutylbipyridine)iridium(III) hexafluorophosphate (Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6) and a mild stoichiometric oxidant such as bromotrichloromethane, BrCCl3.

[20] The photoexcited iridium catalyst is reducing enough to fragment the bromotrichloromethane to form a trichloromethyl radical, bromide anion, and the Ir(IV) complex.

The electron-poor fluorinated ligands makes the iridium complex oxidising enough to accept an electron from an electron-rich arene such as a PMB ether.

Cycloadditions and other pericyclic reactions are powerful transforms in organic synthesis because of their potential to rapidly generate complex molecular architectures and particularly because of their capacity to set multiple adjacent stereocenters in a highly controlled manner.

Under uncatalyzed conditions, this activation requires the use of high energy ultraviolet light capable of altering the orbital populations of the reactive compounds.

The required change in orbital populations can be achieved by electron transfer with a photocatalyst sensitive to lower energy visible light.

Enones, or electron-poor olefins, were discovered to react via a radical-anion pathway, utilizing diisopropylethylamine as a transient source of electrons.

The anionic nature of the cyclization proved to be crucial: performing the reaction in acid rather than with a lithium counterion favored a non-cycloaddition pathway.

[27] Conversely, electron-rich styrenes were found to react via a radical-cation mechanism, utilizing methyl viologen or molecular oxygen as a transient electron sink.

For intermolecular cyclizations, Yoon et al. discovered that the more strongly oxidizing photocatalyst [Ru(bpm)3]2+ and molecular oxygen provided a catalytic system better suited to access the radical cation necessary for the cycloaddition to occur.

Bis-enones, similar to the substrates used for the photoredox [2+2] cyclization, but with a longer linker joining the two enone functional groups, undergo intramolecular radical-anion hetero-Diels–Alder reactions more rapidly than [2+2] cycloaddition.

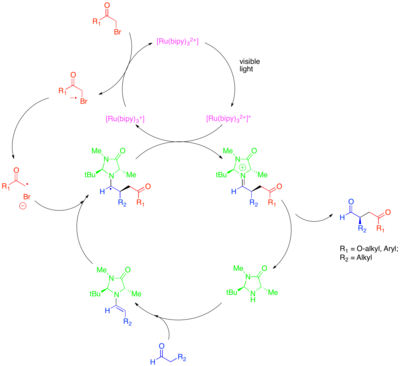

[32] In this approach for the α-alkylation of aldehydes, [Ru(bipy)3]2+ reductively fragments an activated alkyl halide, such as bromomalonate or phenacyl bromide, which can then add to catalytically-generated enamine in an enantioselective manner.

This photoredox transformation was shown to be mechanistically distinct from another organocatalytic radical process termed singly-occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) catalysis.

SOMO catalysis employs superstoichiometric ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) to oxidize the catalytically-generated enamine to the corresponding radical cation, which can then add to a suitable coupling partner such as allyl silane.

[37] This transformation, which like other photoredox processes takes place by a radical mechanism, is limited to the addition of highly electrophilic arenes to the beta position.

The photocatalyst then oxidizes an enamine species, transiently generated by the condensation of an aldehyde with a secondary amine cocatalyst, such as the optimal isopropyl benzylamine.

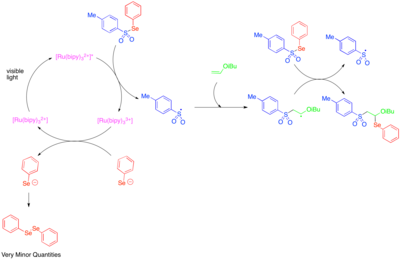

[40][41] These reactions use Umemoto's reagent, a sulfonium salt that serves as an electrophilic source of the trifluoromethyl group and that is precedented to react via a single-electron transfer pathway.

Subsequently, single-electron oxidation of the alkyl radical generated by this addition produces a cation which can be trapped by water, an alcohol, or a nitrile.

In order to achieve high levels of regioselectivity, this reactivity has been explored mainly for styrenes, which are biased towards formation of the benzylic radical intermediate.

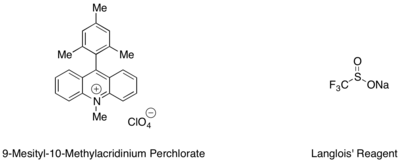

Hydrotrifluoromethylation of styrenes and aliphatic alkenes can be effected with a mesityl acridinium organic photoredox catalyst and Langlois' reagent as the source of CF3 radical.

[42] In this reaction, it was found that trifluoroethanol and substoichiometric amounts of an aromatic thiol, such as methyl thiosalicylate, employed in tandem served as the best source of hydrogen radical to complete the catalytic cycle.