Cycloaddition

[2] As a class of addition reaction, cycloadditions permit carbon–carbon bond formation without the use of a nucleophile or electrophile.

[1] A more recent, IUPAC-preferred notation, first introduced by Woodward and Hoffmann, uses square brackets to indicate the number of electrons, rather than carbon atoms, involved in the formation of the product.

They usually have (4n + 2) π electrons participating in the starting material, for some integer n. These reactions occur for reasons of orbital symmetry in a suprafacial-suprafacial (syn/syn stereochemistry) in most cases.

Strained alkenes like trans-cycloheptene derivatives have also been reported to react in an antarafacial manner in [2 + 2]-cycloaddition reactions.

Doering (in a personal communication to Woodward) reported that heptafulvalene and tetracyanoethylene can react in a suprafacial-antarafacial [14 + 2]-cycloaddition.

However, this reaction was later found to be stepwise, as it also produced the Woodward-Hoffmann forbidden suprafacial-suprafacial product under kinetic conditions.

[3] Erden and Kaufmann had previously found that the cycloaddition of heptafulvalene and N-phenyltriazolinedione also gave both suprafacial-antarafacial and suprafacial-suprafacial products.

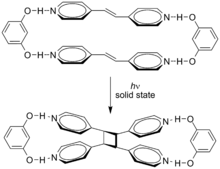

[5] The two trans alkenes react head-to-tail, and the isolated isomers are called truxillic acids.

The key distinguishing feature of cheletropic reactions is that on one of the reagents, both new bonds are being made to the same atom.

One example of a formal [3+3]cycloaddition between a cyclic enone and an enamine catalyzed by n-butyllithium is a Stork enamine / 1,2-addition cascade reaction:[7] Iron[pyridine(diimine)] catalysts contain a redox active ligand in which the central iron atom can coordinate with two simple, unfunctionalized olefin double bonds.

![An intermolecular formal [3+3] cycloaddition between an cyclic iminium chloride and cyclopentenone.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/3%2B3_cycloaddition_-_cyclic_iminium_to_cyclic_enone.svg/500px-3%2B3_cycloaddition_-_cyclic_iminium_to_cyclic_enone.svg.png)