Phylogenetic tree

[1][2] In other words, it is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological species or other entities based upon similarities and differences in their physical or genetic characteristics.

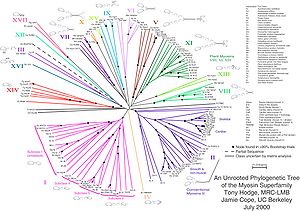

In evolutionary biology, all life on Earth is theoretically part of a single phylogenetic tree, indicating common ancestry.

The main challenge is to find a phylogenetic tree representing optimal evolutionary ancestry between a set of species or taxa.

Internal nodes are generally called hypothetical taxonomic units, as they cannot be directly observed.

Unrooted trees illustrate only the relatedness of the leaf nodes and do not require the ancestral root to be known or inferred.

[citation needed] The most common method for rooting trees is the use of an uncontroversial outgroup—close enough to allow inference from trait data or molecular sequencing, but far enough to be a clear outgroup.

[6] Unrooted trees illustrate the relatedness of the leaf nodes without making assumptions about ancestry.

Some sequence-based trees built from a small genomic locus, such as Phylotree,[10] feature internal nodes labeled with inferred ancestral haplotypes.

The last distinction is the most biologically relevant; it arises because there are many places on an unrooted tree to put the root.

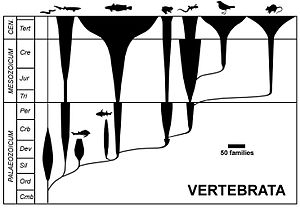

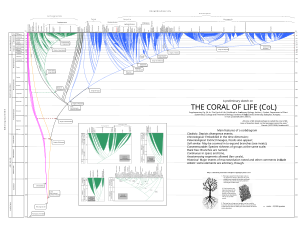

Indeed, phylogenetic corals are useful for portraying past and present life, and they have some advantages over trees (anastomoses allowed, etc.).

Distance-matrix methods such as neighbor-joining or UPGMA, which calculate genetic distance from multiple sequence alignments, are simplest to implement, but do not invoke an evolutionary model.

More advanced methods use the optimality criterion of maximum likelihood, often within a Bayesian framework, and apply an explicit model of evolution to phylogenetic tree estimation.

Standardized formats are critical for distributing and sharing trees without relying on graphics output that is hard to import into existing software.

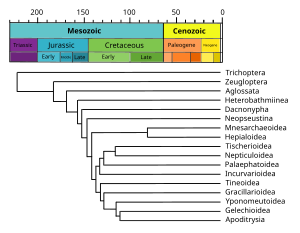

Commonly used formats are Although phylogenetic trees produced on the basis of sequenced genes or genomic data in different species can provide evolutionary insight, these analyses have important limitations.

Also, there are problems in basing an analysis on a single type of character, such as a single gene or protein or only on morphological analysis, because such trees constructed from another unrelated data source often differ from the first, and therefore great care is needed in inferring phylogenetic relationships among species.

For this reason, serious phylogenetic studies generally use a combination of genes that come from different genomic sources (e.g., from mitochondrial or plastid vs. nuclear genomes),[26] or genes that would be expected to evolve under different selective regimes, so that homoplasy (false homology) would be unlikely to result from natural selection.

Phylogenetic networks are used when bifurcating trees are not suitable, due to these complications which suggest a more reticulate evolutionary history of the organisms sampled.