Phylogenetic nomenclature

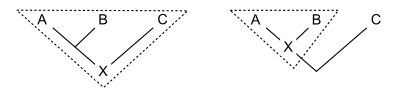

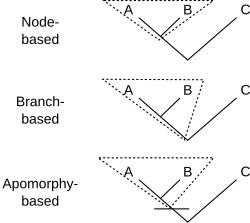

However, it is also possible to create definitions for the names of other groups that are phylogenetic in the sense that they use only ancestral relations based on species or specimens.

Names of polyphyletic groups, characterized by a trait that evolved convergently in two or more subgroups, can be defined similarly as the sum of multiple clades.

[citation needed] The current codes have rules stating that names must have certain endings depending on the rank of the taxa to which they are applied.

He noted that Simpson in 1963 and Wiley in 1981 agreed that the same group of genera, which included the genus Homo, should be placed together in a taxon.

For botany, the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, responsible for the currently most widely used classification of flowering plants, chose a different method.

[citation needed] The conflict between phylogenetic and traditional nomenclature represents differing opinions of the metaphysics and epistemology of taxa.

[17] Given the metaphysical claims regarding unobservable entities made by advocates of phylogenetic nomenclature, critics have referred to their method as origin essentialism.

As "Pelycosauria" refers to a paraphyletic group that includes some Permian tetrapods but not their extant descendants, it cannot be admitted as a valid taxon name.

Monophyletic groups are worthy of attention and naming because they share properties of interest -- synapomorphies -- that are the evidence that allows inference of common ancestry.

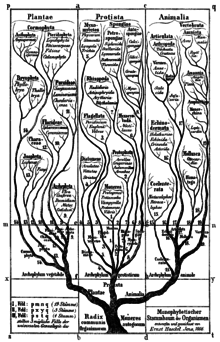

[22] Phylogenetic nomenclature is a semantic extension of the general acceptance of the idea of branching during the course of evolution, represented in the diagrams of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and later writers like Charles Darwin and Ernst Haeckel.

In it, Haeckel introduced the rank of phylum which carries a connotation of monophyly in its name (literally meaning "stem").

From the 1960s onwards, rankless classifications were occasionally proposed, but in general the principles and common language of traditional nomenclature have been used by all three schools of thought.

[citation needed] Most of the basic tenets of phylogenetic nomenclature (lack of obligatory ranks, and something close to phylogenetic definitions) can, however, be traced to 1916, when Edwin Goodrich[26] interpreted the name Sauropsida, defined 40 years earlier by Thomas Henry Huxley, to include the birds (Aves) as well as part of Reptilia, and invented the new name Theropsida to include the mammals as well as another part of Reptilia.

As these taxa were separate from traditional zoological nomenclature, Goodrich did not emphasize ranks, but he clearly discussed the diagnostic features necessary to recognize and classify fossils belonging to the various groups.

It is clear, then, that we have here a valuable corroborative character to help us to decide whether a given species belongs to the Theropsidan or the Sauropsidan line of evolution."

Goodrich concluded his paper: "The possession of these characters shows that all living Reptilia belong to the Sauropsidan group, while the structure of the foot enables us to determine the affinities of many incompletely known fossil genera, and to conclude that only certain extinct orders can belong to the Theropsidan branch."

In an attempt to avoid a schism among the systematics community, "Gauthier suggested to two members of the ICZN to apply formal taxonomic names ruled by the zoological code only to clades (at least for supraspecific taxa) and to abandon Linnean ranks, but these two members promptly rejected these ideas".

Nonetheless, most taxonomists presently avoid paraphyletic groups whenever they think it is possible within Linnaean taxonomy; polyphyletic taxa have long been unfashionable.

Many cladists claim that the traditional Codes of Zoological and Botanical Nomenclature are fully compatible with cladistic methods, and that there is no need to reinvent a system of names that has functioned well for 250 years,[38][39][40] but others argue that this system is not as effective as it should be and that it is time to adopt nomenclatural principles that represent divergent evolution as a mechanism that explains much of the known biodiversity.