Physical organic chemistry

Physical organic chemists use theoretical and experimental approaches work to understand these foundational problems in organic chemistry, including classical and statistical thermodynamic calculations, quantum mechanical theory and computational chemistry, as well as experimental spectroscopy (e.g., NMR), spectrometry (e.g., MS), and crystallography approaches.

[1][page needed] The term physical organic chemistry was itself coined by Louis Hammett in 1940 when he used the phrase as a title for his textbook.

This includes experiments to measure or determine the enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and Gibbs' free energy (ΔG) of a reaction, transformation, or isomerization.

Physical organic chemists use conformational analysis to evaluate the various types of strain present in a molecule to predict reaction products.

[7][8][9] A number of recent articles have investigated the predominance of the steric, electrostatic, and hyperconjugative contributions to rotational barriers in ethane, butane, and more substituted molecules.

Chemists use a series of factors developed from physical chemistry -- electronegativity/Induction, bond strengths, resonance, hybridization, aromaticity, and solvation—to predict relative acidities and basicities.

Unlike thermodynamics, which is concerned with the relative stabilities of the products and reactants (ΔG°) and their equilibrium concentrations, the study of kinetics focuses on the free energy of activation (ΔG‡) -- the difference in free energy between the reactant structure and the transition state structure—of a reaction, and therefore allows a chemist to study the process of equilibration.

[1][page needed] Mathematically derived formalisms such as the Hammond Postulate, the Curtin-Hammett principle, and the theory of microscopic reversibility are often applied to organic chemistry.

[12][page needed] Rate laws must be determined by experimental measurement and generally cannot be elucidated from the chemical equation.

Determination of the rate law was historically accomplished by monitoring the concentration of a reactant during a reaction through gravimetric analysis, but today it is almost exclusively done through fast and unambiguous spectroscopic techniques.

[12][page needed] A catalyst lowers the activation energy barrier (ΔG‡), increasing the rate of a reaction by either stabilizing the transition state structure or destabilizing a key reaction intermediate, and as only a small amount of catalyst is required it can provide economic access to otherwise expensive or difficult to synthesize organic molecules.

[1][page needed] This analysis compares the effect of various substituents on the ionization of benzoic acid with their impact on diverse chemical systems.

This is a case where understanding the effect of solvent on the stability of the molecular configuration of a reagent is important with regard to the selectivity observed in an asymmetric synthesis.

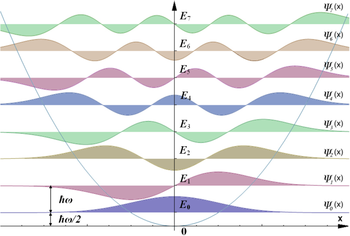

[citation needed] The power of quantum chemistry is built on the wave model of the atom, in which the nucleus is a very small, positively charged sphere surrounded by a diffuse electron cloud.

For this reason, nuclei are of negligible size in relation to much lighter electrons and are treated as point charges in practical applications of quantum chemistry.

Due to complex interactions which arise from electron-electron repulsion, algebraic solutions of the Schrödinger equation are only possible for systems with one electron such as the hydrogen atom, H2+, H32+, etc.

Importantly, the solutions for atoms with multiple electrons give properties such as diameter and electronegativity which closely mirror experimental data and the patterns found in the periodic table.

The solutions for molecules, such as methane, provide exact representations of their electronic structure which are unobtainable by experimental methods.

[citation needed] Instead of four discrete σ-bonds from carbon to each hydrogen atom, theory predicts a set of four bonding molecular orbitals which are delocalized across the entire molecule.

Solving a complete energy surface for a given reaction is therefore possible, and such calculations have been applied to many problems in organic chemistry where kinetic data is unavailable or difficult to acquire.

[1][page needed] Physical organic chemistry often entails the identification of molecular structure, dynamics, and the concentration of reactants in the course of a reaction.

An external magnetic field applied to a paramagnetic nucleus generates two discrete states, with positive and negative spin values diverging in energy; the difference in energy can then be probed by determining the frequency of light needed to excite a change in spin state for a given magnetic field.

[22] It is possible to quantify the relative concentration of different organic molecules simply by integration peaks in the spectrum, and many kinetic experiments can be easily and quickly performed by following the progress of a reaction within one NMR sample.

[1][page needed] Vibrational spectroscopy, or infrared (IR) spectroscopy, allows for the identification of functional groups and, due to its low expense and robustness, is often used in teaching labs and the real-time monitoring of reaction progress in difficult to reach environments (high pressure, high temperature, gas phase, phase boundaries).

Molecular vibrations are quantized in an analogous manner to electronic wavefunctions, with integer increases in frequency leading to higher energy states.

Further complicating matters is that some vibrations do not induce a change in the molecular dipole moment and will not be observable with standard IR absorption spectroscopy.

However, as Raman spectroscopy relies on light scattering it can be performed on microscopic samples such as the surface of a heterogeneous catalyst, a phase boundary, or on a one microliter (μL) subsample within a larger liquid volume.

[25] Combined gas chromatography and mass spectrometry is used to qualitatively identify molecules and quantitatively measure concentration with great precision and accuracy, and is widely used to test for small quantities of biomolecules and illicit narcotics in blood samples.

Unlike spectroscopic methods, X-ray crystallography always allows for unambiguous structure determination and provides precise bond angles and lengths totally unavailable through spectroscopy.

It is often used in physical organic chemistry to provide an absolute molecular configuration and is an important tool in improving the synthesis of a pure enantiomeric substance.