Pickett's Charge

It was ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee as part of his plan to break through Union lines and achieve a decisive victory in the North.

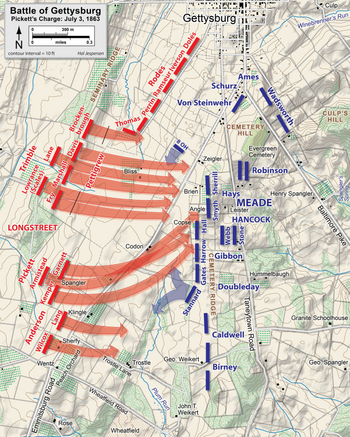

As the Confederate troops marched across nearly a mile of open ground, they came under heavy artillery and rifle fire from entrenched Union forces.

Although a small number of the Confederate soldiers managed to reach the Union lines and engage in hand-to-hand combat, they were ultimately overwhelmed.

The failure of the charge crushed the Confederate Army's hopes of winning a decisive victory in the North and forced General Lee to retreat back to Virginia.

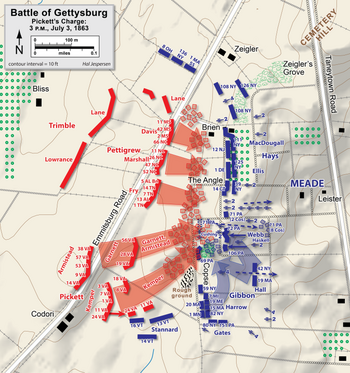

However, recent scholarship, including published works by some Gettysburg National Military Park historians, has suggested that Lee's goal was actually Ziegler's Grove on Cemetery Hill, a more prominent and highly visible grouping of trees about 300 yards (274 m) north of the copse.

The copse of trees, currently a prominent landmark, was under ten feet (3 m) high in 1863, visible to a portion of the attacking columns only from certain parts of the battlefield.

Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart led his cavalry division to the east, prepared to exploit Lee's hoped-for breakthrough by attacking the Union rear and disrupting its line of communications (and retreat) along the Baltimore Pike.

Historian Jeffrey D. Wert blames this oversight on Longstreet, describing it either as a misunderstanding of Lee's oral order or a mistake.

Lee's intent was to synchronize his offensive across the battlefield, keeping Meade from concentrating his numerically superior force, but the assaults were poorly coordinated and Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's attacks against Culp's Hill petered out just as Longstreet's cannonade began.

Looking up the valley towards Gettysburg, the hills on either side were capped with crowns of flame and smoke, as 300 guns, about equally divided between the two ridges, vomited their iron hail upon each other.

Hunt had to resist the strong arguments of Hancock, who demanded Union fire to lift the spirits of the infantrymen pinned down by Alexander's bombardment.

For the rest of his life, Hunt always maintained that had he been allowed to do what he'd intended—saved his long range shells for the attack he knew was coming, then bombarded the Confederate forces with every gun available once they lined up for their advance—the charge would never have happened and many northern lives would have been saved.

When Union cannoneers overshot their targets, they often hit the massed infantry waiting in the woods of Seminary Ridge or in the shallow depressions just behind Alexander's guns, causing significant casualties before the charge began.

[33]Longstreet wanted to avoid personally ordering the charge by attempting to pass the mantle onto young Colonel Alexander, telling him that he should inform Pickett at the optimum time to begin the advance, based on his assessment that the Union artillery had been effectively silenced.

Longstreet ordered Alexander to stop Pickett, but the young colonel explained that replenishing his ammunition from the trains in the rear would take over an hour, and this delay would nullify any advantage the previous barrage had given them.

[note 7] Over two-thirds of the initial force may have failed to make the final charge; at contact the mile-long front had shrunk to less than half a mile, as the men filled in gaps that appeared throughout the line and followed the natural tendency to move away from the flanking fire.

The 160 Ohioans, firing from a single line, so surprised Brockenbrough's Virginians—already demoralized by their losses to artillery fire—that they panicked and fled back to Seminary Ridge, crashing through Trimble's division and causing many of his men to bolt as well.

Scales's North Carolina brigade, led by Col. William L. J. Lowrance, started with a heavier disadvantage—they had lost almost two-thirds of their men on July 1.

At about this time, Hancock, who had been prominent in displaying himself on horseback to his men during the Confederate artillery bombardment, was wounded by a bullet striking the pommel of his saddle, entering his inner right thigh along with wood fragments and a large bent nail.

[49] As Pickett's men advanced, they withstood the defensive fire of first Stannard's brigade, then Harrow's, and then Hall's, before approaching a minor salient in the Union center, a low stone wall taking an 80-yard right-angle turn known afterward as "The Angle".

In the latter case, this left Captain Andrew Cowan and his 1st New York Independent Artillery Battery to face the oncoming infantry.

Assisted personally by artillery chief Henry Hunt, Cowan ordered five guns to fire double canister simultaneously.

In particular North Carolinians have long taken exception to the characterizations and point to the poor performance of Brockenbrough's Virginians in the advance as a major causative factor of failure.

The fact that fifteen of his officers and all three of his brigadier generals were casualties while Pickett managed to escape unharmed led many to question his proximity to the fighting and, by implication, his personal courage.

[65] Proponents extol the bravery of Confederate soldiers attacking headlong into Union lines, the capable leadership of southern generals inspiring overwhelming confidence in their men, especially that of Virginians such as Lee and Pickett, and the tantalizing closeness of ultimate victory.

William Faulkner, the quintessential Southern novelist, summed up the picture in Southern myth of this gallant but futile episode:[66] For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it's still not yet two o'clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it's all in the balance, it hasn't happened yet, it hasn't even begun yet, it not only hasn't begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances which made more men than Garnett and Kemper and Armistead and Wilcox look grave yet it's going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn't need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think This time.

[note 11] Northern veterans in particular opposed the decreasing emphasis on their hard-fought defense of Cemetery Ridge in favor of extolling the bravery and sacrifice of the attacking Confederate army.

[73] Examination of casualty records, capture reports, and first hand accounts has revealed that substantial numbers of Confederate troops involved in the attack refused to make the final charge, instead choosing to shelter in the sunken depression of the Emmitsburg Road and surrender to Union soldiers after the battle.

[44] And later research has shown that it is unlikely Pickett's charge could ever have provided the decisive victory imagined by Lee; a study using the Lanchester model to examine several alternative scenarios suggested that Lee could have captured a foothold on Cemetery Ridge if he had committed several more infantry brigades to the charge; but this likely would have left him with insufficient reserves to hold or exploit the position afterwards.

The National Park Service maintains a neat, mowed path alongside a fence that leads from the Virginia Monument on West Confederate Avenue (Seminary Ridge) due east to the Emmitsburg Road in the direction of the Copse of Trees.