Pike and shot

The chastened Spanish undertook a thorough reorganization of their army and tactics under the great captain Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba ("El Gran Capitán").

This was especially necessary because the firearms of the early 16th century were inaccurate, took a very long time to load and only had a short range, meaning the shooters were often only able to get off a few shots before the enemy was upon them.

For example, in the Wars of Religion of the 1560s and 1570s, 54% of wounds suffered by French soldiers were inflicted by swords, these being the most common weapons on the battlefield as pikemen, halberdiers, arquebusiers, musketeers, and cavalry all carried them as sidearms.

[5] In preparation for the Third Italian War of 1502 to 1504, Spanish general Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba set his companies at 50% pikes, 33% swords and shields, and 17% arquebuses.

[9] For landsknechts in general, the usual arrangement was that one Fähnlein, the standard unit, had 400 men, of whom 300 were pikemen (75%), 50 were arquebusiers (12.5%), and 50 were halberdiers or two-handed swordsmen (12.5%).

[15] A study of a selection of Dutch companies from 1587, standardized by William of Orange, showed 34% pikes, 9% halberds, 5% swords and bucklers, and 52% firearms.

[17] Lansdowne MS 56, attributed to Lord Burghley, states that ideally infantry formations should consist of 50% shot, 30% pikes, and 20% billhooks.

A cavalry brigade of 2,988 men was to be equipped with 1,152 bows, 432 arquebuses, and 60 "crouching tigers", miniature bombards loaded with one hundred pellets each, essentially 21.6 kg blunderbusses (20% firearms).

[21] Contemporary Japanese units, while heavily focused on firearms by East Asian standards, had higher ratios of other weapons to arquebuses compared to late 16th to early 17th century European formations.

[29] The rapidly rising percentage of firearms spurred by pike-and-shot battles, until reaching near-100% by the 18th century, was generally not mirrored in non-European countries that did not adopt such tactics.

Nor was the proliferation of the flintlock; matchlocks remained the most common firearms in India, China, and Southeast Asia until about the mid-19th century due to being far less complicated to manufacture.

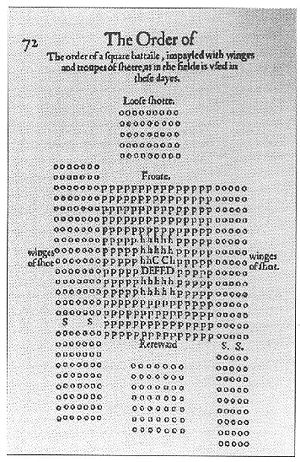

These companies were further subdivided into small units that could be deployed individually or brought together to form great battle formations that were sometimes called "Spanish squares".

Normal attrition of combat units (including sickness and desertion) and the sheer lack of men usually led to the tercios being far smaller in practice than the numbers above suggest but the roughly 1:1 ratio of pikemen to shooters was generally maintained.

To modern eyes the tercio square seems cumbersome and wasteful of men, many of the soldiers being positioned so that they could not bring their weapons to bear against the enemy.

It was very hard to isolate or outflank and destroy a tercio by maneuver due to its great depth and distribution of firepower to all sides (as opposed to the maximization of combat power in the frontal arc as adopted by later formations).

The individual units of pikemen and musketeers were not fixed and were re-ordered during battle to defend a wing or to bring greater fire power or pikes to bear in a certain direction.

Finally, its depth meant that it could run over shallower formations in a close assault – that is, should the slow-moving tercio manage to strike the enemy line.

Movement of such seemingly unwieldy groups of soldiers was difficult but well-trained and experienced tercios were able to move and manoeuvre with surprising facility and to great advantage over less-experienced opponents.

The French military establishment showed considerably less interest in shot as a native troop type than did the Spanish until the end of the sixteenth century, and continued to prefer close combat arms, particularly heavy cavalry, as the decisive force in their armies until the French Wars of Religion; this despite the desire of King Francis I to establish his own pike and shot contingents after the Battle of Pavia, in which he was defeated and captured.

Francis had declared the establishment of the French "Legions" in the 1530s, large infantry formations of 6,000 men which were roughly composed of 60% pikemen, 30% arquebusiers and 10% Halberdiers.

This was essentially the condition of the French Royal infantry throughout the French Wars of Religion that occupied most of the latter sixteenth century, and when their Huguenot foes had to improvise a native infantry force, it was largely made up of arquebusiers with few if any pikes (other than the large blocks of Landsknechts they sometimes hired), rendering formal pike and shot tactics impossible.

Although the battle was ultimately lost by the Spanish and Imperial forces, it demonstrated the self-sufficiency of the mixed pike and shot formations, something sorely lacking in the French armies of the day.

In addition to standardizing drill, weapon caliber, pike length, and so on, Maurice turned to his readings in classical military doctrine to establish smaller, more flexible combat formations than the ponderous regiments and tercios which then presided over open battle.

In the end, Maurice's armies depended primarily on defensive siege warfare to wear down the Spanish attempting to wrest control of the heavily fortified towns of the Seven Provinces, rather than risking the loss of all through open battle.

Finally, he embedded four small "infantry guns" into each battalion, allowing them to move about independently and not suffer from a lack of cannon fire if they became detached.

The Japanese army in the Imjin War supported their gunmen (25–30% of their initial force) with spear and bow levies, but the pike was not as emphasized as it was in contemporary Europe due to the lack of a large cavalry threat in either Japan or Korea.

At the 1619 Battle of Sarhū, the Koreans (drawing on lessons from 1592 to 1598) deployed an all-shot formation (10,000 arquebusiers and 3,000 archers) using volley fire against the cavalry-heavy Manchus.

The first emperor of the newly declared Qing dynasty later wrote: "The Koreans are incapable on horseback but do not transgress the principles of the military arts.

Even later, the obsolete pike would still find a use in such countries as Ireland, Russia, and China, generally in the hands of desperate peasant rebels who did not have access to firearms.

One attempt to resurrect the pike as a primary infantry weapon occurred during the American Civil War when the Confederate States of America[citation needed] planned to recruit twenty regiments of pikemen in 1862.