Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Told from a first-person point of view, the book details Dillard's explorations near her home, and various contemplations on nature and life.

The book records the narrator's thoughts on solitude, writing, and religion, as well as scientific observations on the flora and fauna she encounters.

Dillard considers the story a "single sustained nonfiction narrative", although several chapters have been anthologized separately in magazines and other publications.

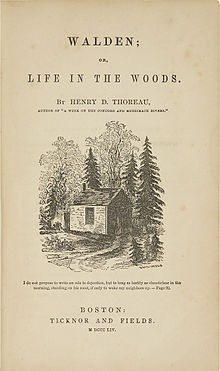

The book is analogous in design and genre to Henry David Thoreau's Walden (1854), the subject of Dillard's master's thesis at Hollins College.

Critics often compare Dillard to authors from the Transcendentalist movement; Edward Abbey in particular deemed her Thoreau's "true heir".

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek was published by Harper's Magazine Press shortly after Dillard's first book, a volume of poetry titled Tickets for a Prayer Wheel.

However, in a nod to his influence, Dillard mentions within the text that she named her goldfish Ellery Channing, after one of Thoreau's closest friends.

Moore specifically recommended that she expand the book's first chapter "to make clear, and to state boldly, what it was [she] was up to," a suggestion that Dillard at first dismissed, but would later admit was good advice.

[15]In the afterword of the 1999 Harper Perennial Modern Classics edition, Dillard states that the book's other, two-part structure mirrors the two routes to God according to neoplatonic christianity: the via positiva and the via negativa.

One of the most famous passages comes from the beginning of the book, when the narrator witnesses a frog being drained and devoured by a giant water bug.

[17] Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is a work of creative nonfiction that uses poetic devices such as metaphor, repetition, and inversion to convey the importance of recurrent themes.

[18] Although it is often described as a series of essays, Dillard has insisted it is a continuous work, as evidenced by references to events from previous chapters.

Critic Donna Mendelson notes that Thoreau's "presence is so potent in her book that Dillard can borrow from [him] both straightforwardly and also humorously.

Unlike Thoreau, Dillard does not make connections between the history of social and natural aspects,[23] nor does she believe in an ordered universe.

Whereas Thoreau refers to the machine-like universe, in which the creator is akin to a master watchmaker, Dillard recognizes the imperfection of creation, in which "something is everywhere and always amiss".

[24] In her review for The New York Times, Eudora Welty noted Pilgrim's narrator being "the only person in [Dillard's] book, substantially the only one in her world .

[26][27] Nancy C. Parrish, author of the 1998 book Lee Smith, Annie Dillard, and the Hollins Group: A Genesis of Writers, notes that despite its having been written in the first person, Pilgrim is not necessarily autobiographical.

"[28] Critic Suzanne Clark also points to the "peculiar evasiveness" of Dillard-the-author, noting that "when we read Annie Dillard, we don't know who is writing.

[35] Margaret Loewen Reimer, in one of the first critical studies based on the book, noted that Dillard's treatment of the metaphysical is similar to that of Herman Melville.

At one point, she sees a cedar tree near her house "charged and transfigured, each cell buzzing with flame" as the light hits it; this burning vision, reminiscent of creation's holy "fire", "comes and goes, mostly goes, but I live for it.

Although a long tradition of male nature writers—including James Fenimore Cooper, Jack London and Richard Nelson—have used this theme as "a symbolic ritual of violence", Dillard "ventures into the terrain of the hunt, employing its rhetoric while also challenging its conventions.

"[39] While some critics describe the book as being more devoted to speculation of the divine and natural world than to self-exploration, others approach it in terms of Dillard's attention to self-awareness.

[45] Dillard was unnerved by the crush of attention; shortly after the book was published, she wrote, "I'm starting to have dreams about Tinker Creek.

Reviewing both volumes for America, John Breslin noted the similarities between the two: "Even if her first book of poems had not been published simultaneously, the language she uses in Pilgrim would have given her away.

"[48] The Saturday Evening Post also praised Dillard's poetic ability in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, noting that "the poet in her is everywhere evident in this prose-poem of hers: the reader's attention is caught not only by the freshness of her insights, but by the beauty of her descriptions as well.

"[49] Melvin Maddocks, a reviewer for Time, noted Dillard's intention of subtle influence: "Reader, beware of this deceptive girl, mouthing her piety about 'the secret of seeing' being 'the pearl of great price,' modestly insisting, 'I am no scientist.

Early reviewers Charles Nicol[51] and J. C. Peirce linked Dillard with the transcendentalist movement, comparing her to Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

[36] Author and environmentalist Edward Abbey, known as the "Thoreau of the American West", stated that Dillard was the "true heir of the Master".