Pink-collar worker

Baumol's focus was not only on the gendered nature of these jobs but also on their economic characteristics, particularly their relatively lower wages and limited opportunities for advancement compared to male-dominated professions.

These positions were seen as extensions of traditional domestic responsibilities and were characterized by lower pay, limited career advancement opportunities, and a lack of prestige compared to "blue-collar" or "white-collar" jobs.

Howe’s analysis went beyond simply identifying these roles; she explored how social expectations, gender norms, and structural inequalities confined women to these positions.

Her work aimed to raise awareness about the economic and social disparities faced by women in the workforce and to advocate for the recognition and improvement of conditions in these roles.

While Baumol's earlier usage of pink collar focused on economic categorizations, Howe expanded the term into a cultural and feminist critique, framing it as part of the broader struggle for gender equality in labour.

[7] Due to the low population of women outside of the childcare or social workforce, state governments are miscalculating economic budgets by not accounting for most female pink-collar workers.

As explained in Buzzanell et al.'s research article, maternity leave is the time off from work a mother takes after having a child, either through childbirth or adoption.

[8] In 2010, the International Labour Office explained that maternity leave is usually compensated by the employer's company, but several countries do not follow that mandate, including the United States.

In the mid 19th and early 20th century women aimed to be treated as equals to their male counterparts, notably in the Seneca Falls Convention.

The women who joined these societies worked with their members, some of whom were full-time teachers, nurses, missionaries, and social workers to accomplish their leadership tasks.

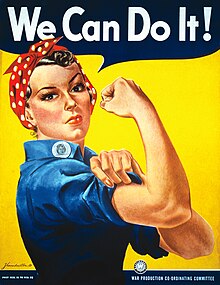

World War I sparked a demand for "pink-collar jobs" as the military needed personnel to type letters, answer phones, and perform other secretarial tasks.

[24] Notably, American women in World War II joined the armed services and were stationed domestically and abroad through participation in non-combat military roles and as medical personnel.

Despite the difficult work, many women wanted this job because it paid five dollars a week and provided a rest lounge for the employees to take a break.

[29] Social workers gave crucial expertise for the expansion of federal, state and local government, as well as services to meet the needs of the Depression.

[29] Teachers in primary and secondary schools remained female, although as the war progressed, women began to move on to better employment and higher salaries.

In the 1940s, clerical work expanded to occupy the largest number of women employees, this field diversified as it moved into commercial service.

[35] As mentioned in the research article by Patrice Buzzanell, Robyn Remke, Rebecca Meisenbach, Meina Liu, Venessa Bowers, and Cindy Conn, as of 2016, pink-collar jobs are quickly growing in demand by both men and women.

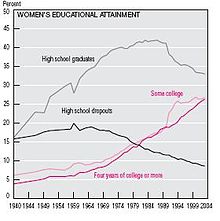

[45] However, opportunities for higher education expanded as women were admitted to all-male schools like the United States service academies and Ivy League strongholds.

Being educated was an expectation for women entering the paying workforce, despite the fact that their male equivalents did not need a high school diploma.

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) was formed after women shirtwaist makers went on strike in New York City in 1909.

It started as a small walkout, with a handful of members from one shop and grew to a force of ten of thousands, changing the course of the labor movement forever.

[51] "Pink ghetto" can also describe the placement of female managers into positions that will not lead them to the board room, thus perpetuating the "glass ceiling".

[57] As noted below in The Mythology of “Pink Collaring”, recent studies by data scientist Felix Busch and others have shown that the devaluation of occupations due to feminization has been declining since the mid-twentieth century, becoming statistically insignificant in 2015.

[60] As noted above, the authors who first described “pink collar” work, including William Jack Baumol, Louise Kapp Howe, Karin Stallard, Barbara Ehrenreich, and Holly Sklar, used the term to criticize the unfair systems trapping women in low-paying jobs.

[67] In “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops,” Miller summarized a 2009 longitudinal study by sociologists Asaf Levanon, Paula England, and Paul Allison demonstrating a consistent twentieth-century trend wherein US occupations with a higher percentage of women offered lower median hourly wages than comparable fields that retained male majorities.

[68] Miller overlooked both the historical nature of Levanon, England, and Allison’s findings and a problem that the authors themselves acknowledged, namely, that they did not investigate the mechanisms driving gender-based workplace devaluation or how resistant it might be to change.

[71] Favoring men in hiring decisions because of their gender is illegal in the United States under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

[74] Robotics and automation have not only eliminated many traditionally male-dominated roles but have also forced men into pink-collar jobs, which are often perceived as less prestigious due to associations with "women's work."

[7] Despite challenges, some men in pink-collar professions achieve advantages such as higher salaries, more opportunities, and faster promotions compared to their female counterparts.

For example, the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that less than 20% of elementary school teachers were men, highlighting the persistent gender imbalance in such fields.