Piracy in the Caribbean

Piracy flourished in the Caribbean because of the existence of pirate seaports such as Fort Saint Louis in Martinique, Port Royal in Jamaica,[1] Castillo de la Real Fuerza in Cuba, Tortuga in Haiti, and Nassau in the Bahamas.

The following quote by an 18th-century Welsh captain shows the motivations for piracy: In an honest Service, there is thin Commons, low Wages, and hard Labour; in this, Plenty and Satiety, Pleasure and Ease, Liberty and Power; and who would not balance Creditor on this Side, when all the Hazard that is run for it, at worst, is only a sower Look or two at choaking.

No, a merry Life and a short one shall be my Motto.—Pirate Captain Bartholomew Roberts[6] Piracy was sometimes given legal status by the colonial powers, especially France under King Francis I (r. 1515–1547), in the hope of weakening Spain and Portugal's mare clausum trade monopolies in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

A treasure fleet or flota would sail annually from Seville (and later from Cádiz) in Spain, carrying passengers, troops, and European manufactured goods to the Spanish colonies of the New World.

The classic route for the treasure fleet in the Caribbean was through the Lesser Antilles to the ports along the Spanish Main on the coast of Central America and New Spain, then northwards into the Yucatán Channel to catch the westerly winds back to Europe.

The Spanish, despite being the most powerful state in Christendom at the time, could not afford a sufficient military presence to control such a vast area of ocean or enforce their exclusionary, mercantilist trading laws.

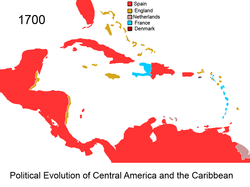

But the relative emptiness of the Caribbean also made it an inviting place for England, France and the Netherlands to set up colonies of their own, especially as gold and silver became less important as commodities to be seized and were replaced by tobacco and sugar as cash crops that could make men very rich.

In the early 17th century, expensive fortifications and the size of the colonial garrisons at the major Spanish ports increased to deal with the enlarged presence of Spain's competitors in the Caribbean, but the treasure fleet's silver shipments and the number of Spanish-owned merchant ships operating in the region declined.

At the same time, England and France were powers on the rise in 17th-century Europe as they mastered their own internal religious schisms between Catholics and Protestants and the resulting societal peace allowed their economies to rapidly expand.

English and French kings of the early 17th century—James I (r. 1603–1625) and Henry IV (r. 1598–1610), respectively, each sought more peaceful relations with Habsburg Spain in an attempt to decrease the financial costs of the ongoing wars.

The Spanish-ruled island of Trinidad was already a wide-open port open to the ships and seamen of every nation in the region at the start of the 17th century, and was a particular favorite for smugglers who dealt in tobacco and European manufactured goods.

Local Caribbean smugglers sold their tobacco or sugar for decent prices and then bought manufactured goods from the trans-Atlantic traders in large quantities to be dispersed among the colonists of the West Indies and the Spanish Main who were eager for a little touch of home.

The English had established an early colony known as Virginia in 1607 and one on the island of Barbados in the West Indies in 1625, although this small settlement's people faced considerable dangers from the local Carib Indians (believed to be cannibals) for some time after its founding.

They would work the colonies and fuel Europe's tobacco, rice and sugar supply; by 1698 England had the largest slave exports with the most efficiency in their labor in relation to any other European imperial power.

After the destruction of Fort Caroline by the Spanish, the French made no further colonization attempts in the Caribbean for several decades as France was convulsed by its own Catholic-Protestant religious divide during the late 16th century Wars of Religion.

The first third of the 17th century in the Caribbean was defined by the outbreak of the savage and destructive Thirty Years' War in Europe (1618–1648), which represented both the culmination of the Protestant-Catholic conflict of the Reformation and the final showdown between Habsburg Spain and Bourbon France.

For France, now ruled by the Bourbon King Louis XIII (r. 1610–1642) and his able minister Cardinal Richelieu, religious civil war had been reignited between French Catholics and Protestants (called Huguenots).

Meanwhile, the Dutch, at last independent of Spain when the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia ended their own Eighty Years War (1568–1648) with the Habsburgs, made a fortune carrying the European trade goods needed by these new colonies.

The English had also expanded their dominion in the Caribbean and settled several new islands, including Bermuda in 1612, Antigua and Montserrat in 1632, and Eleuthera in the Bahamas in 1648, though these settlements began like all the others as relatively tiny communities that were not economically self-sufficient.

The late 17th and early 18th centuries (particularly between the years 1706 to 1726) are often considered the "Golden Age of Piracy" in the Caribbean, and pirate ports experienced rapid growth in the areas in and surrounding the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Meanwhile, King Louis XIV of France (r. 1642–1715) had finally assumed his majority with the death of his regent mother Queen Anne of Austria's chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, in 1661.

But the depredations of the pirates and buccaneers in the Americas in the latter half of the 17th century and of similar mercenaries in Germany during the Thirty Years' War had taught the rulers and military leaders of Europe that those who fought for profit rather than for King and Country could often ruin the local economy of the region they plundered, in this case the entire Caribbean.

Although some piracy would always remain until the mid-18th century, the path to wealth in the Caribbean in the future lay through peaceful trade, the growing of tobacco, rice and sugar and smuggling to avoid the British Navigation Acts and Spanish mercantilist laws.

The sugar islands of Guadaloupe and Martinique remained the twin economic capitals of the French Lesser Antilles, and were now equal in population and prosperity to the largest of the English's Caribbean colonies.

Also contributing to the increase of Caribbean piracy at this time was Spain's breakup of the British logwood settlement at Campeche and the attractions of a freshly sunken Spanish treasure fleet carrying silver off the southern Bahamas in 1715.

These privateers were rarely scrupulous about adhering to the terms of their letters of marque even during the Wars of Independence, and continued to plague the Caribbean as outright pirates long after those conflicts ended.

[2] Furthermore, some of the ways for deciding disagreements among pirate crew members were fighting till first blood or in more serious cases abandoning an individual on an uninhabited island, whipping them 39 times, or even executing them by firearm.

Noted as much for his outlandish appearance as for his piratical success, in combat Blackbeard placed burning slow-match (a type of slow-burning fuse used to set off cannon) under his hat; with his face wreathed in fire and smoke, his victims claimed he resembled a fiendish apparition from Hell.

Morgan's most famous exploit came in late 1670 when he led 1700 buccaneers up the pestilential Chagres River and then through the Central American jungle to attack and capture the "impregnable" city of Panama.

[40] While on the average 12-week journey to the colonies, the new slaves endured ghastly living conditions that included cramped spaces too small to stand up in, hot temperatures, and poor diets.