Piri Reis map

When rediscovered in 1929, the remaining fragment garnered international attention as it includes a partial copy of an otherwise lost map by Christopher Columbus.

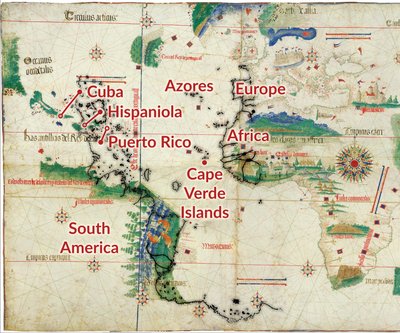

Scholars attribute the peculiar arrangement of the Caribbean to a now-lost map from Columbus that merged Cuba into the Asian mainland and Hispaniola with Marco Polo's description of Japan.

[3] Some authors have noted visual similarities to parts of the Americas not officially discovered by 1513, but there is no textual or historical evidence that the map represents land south of present-day Cananéia.

[5] Much of Piri Reis's biography is known only from his cartographic works, including his two world maps and the Kitab-ı Bahriye (Book of Maritime Matters)[6] completed in 1521.

[21] They showed the parchment to orientalist Paul E. Kahle, who identified it as a creation of Piri Reis citing a source map from Colombus's voyages to the Americas.

[21] Turkey's first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, took an interest in the map and initiated projects to publish facsimiles and conduct research.

[32] The large island oriented vertically is labeled Hispaniola, and the western coast includes elements of Cuba and Central America.

[46] Ptolemy's book was widely printed during the sixteenth century, accompanied by maps from Nicolaus Germanus and Maximus Planudes.

[52] The attitudes towards the Age of Discovery within the Ottoman Empire ranged from passive indifference to the outright rejection of foreign influence.

[56] In the 1526 version of Piri Reis' atlas, the Kitab-ı Bahriye, he explicitly credits European discoveries to lost works created during legendary voyages of Alexander.

[57] Compared to the planisphere and the earlier map of Juan de la Cosa (1500): the Atlantic Ocean is accurate, South America is highly detailed, and the Caribbean is strangely organized.

[k] Piri Reis adapted the elements of iconography from the traditional maps—which illustrated well-known routes, cities, and peoples—to the portolan portrayals of newly discovered coasts.

[66] Historian Karen Pinto has proposed that the egg etymology is better understood in the context of traditional attitudes towards the deep seas in Islamic culture.

[71][72] The caption states that despite the monsters' appearance, they "are harmless souls,"[73] which contrasts with previous depictions of both the headless men and the edge of the known world.

[64] Pinto characterized the map's monsters as, "a distinct break with earlier, and in fact, co-terminus manuscript traditions, which enforce and reinforce the notion that the Encircling Ocean is full of scary beasts and therefore should not be crossed.

[76] The multi-horned beast on the bottom edge of the map may represent the legendary shadhavar, said to emit music as wind blows through its hollow horns.

Columbus compelled his men to swear that Cuba was a part of Asia and agree to never contradict this interpretation "under a penalty of 10,000 maravedis and the cutting out of the tongue".

[80] Columbus traveled West with a chart from Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli that—west of the Canary Islands—showed open ocean, mythical Antilia, and Cipangu (Marco Polo's Japan) between Europe and Asia.

[80] The absence of the island's distinctive Gulf of Gonâve is more evidence of a Columbian origin because he did not explore Hispaniola's western shore.

[83] The peninsulas protruding from Puerto Rico are not present in reality but are also depicted on the map of Juan de la Cosa, who sailed with Columbus.

Some authors have claimed that it depicts areas of South America not officially discovered in 1513, and a popular but disproven hypothesis alleges it to be Antarctica.

[91] Discoveries, like Tierra del Fuego and New Holland,[92] were initially mapped as the northern edge of the unknown southern land.

As these areas were mapped, Terra Australis shrank, grew vague, and became a fantastical locale invoked in literature, notably Gulliver's Travels and Gabriel de Foigny's La Terre Australe Connue.

[93] Belief in the Southern Continent was abandoned after the second voyage of James Cook in the 1770s showed that if it existed, it was much smaller than imagined previously.

Some modern writers have interpreted this coastline as the coast of South America, either drawn along the map's edge or distorted to push it East of the line of demarcation.

[99] The Antarctic claim originates with Captain Arlington H. Mallery,[100] a civil engineer and amateur archaeologist who was a supporter of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact hypotheses.

For example, he designated an island to be one-half of Cuba—claiming it was "wrongly labeled Espaniola" or Hispaniola—and remarked that, "nothing could better illustrate how ignorant Piri Re'is was of his own map.

"[106] Hapgood, and his graduate students who aided with the research, were influential in spreading the idea that the Piri Reis map shows Antarctica as it looked during the Neolithic, without glacial ice.

[107] Two letters reproduced in Hapgood's book express optimism about this hypothesis based on the 1949 Norwegian-British-Swedish Seismic Survey of Queen Maud Land.

[110] Writers like Erich von Daniken,[111] Donald Keyhoe,[107] and Graham Hancock[112] have uncritically repeated Hapgood's claims as proof of ancient astronauts, flying saucers, and a lost civilization comparable to Atlantis, respectively.