William Pitt the Younger

Pitt's prime ministerial tenure, which came during the reign of King George III, was dominated by major political events in Europe, including the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars.

According to Wilberforce, Pitt had an exceptional wit along with an endearingly gentle sense of humour: "no man ... ever indulged more freely or happily in that playful facetiousness which gratifies all without wounding any.

At the end of a long description of Britain's eminent leader he added: ‘Of all the places where you have been, where did you fare best?’ My answer was, ‘In Poland; for the nobility live there with uncommon taste and splendour; their cooks are French,- their confectioners Italian, - and their wine Tokey.’ He immediately observed, ‘I have heard before of The Polish diet.’[18] In 1776, Pitt, plagued by poor health, took advantage of a little-used privilege available only to the sons of noblemen, and chose to graduate without having to pass examinations.

Pitt's father was said to have insisted that his son spontaneously translate passages of classical literature orally into English, and declaim impromptu upon unfamiliar topics in an effort to develop his oratorical skills.

Sinclair noted that there was ‘utter astonishment … by an audience accustomed to the most splendid efforts of eloquence.’[28] Pitt originally aligned himself with prominent Whigs such as Charles James Fox.

The war revealed the limitations of Britain's fiscal-military state when it had powerful enemies and no allies, depended on extended and vulnerable transatlantic lines of communication, and was faced for the first time since the 17th century by both Protestant and Catholic foes.

[33] The Fox–North Coalition fell in December 1783, after Fox had introduced Edmund Burke's bill to reform the East India Company to gain the patronage he so greatly lacked while the king refused to support him.

Following the bill's failure in the Upper House, George III dismissed the coalition government and finally entrusted the premiership to William Pitt, after having offered the position to him three times previously.

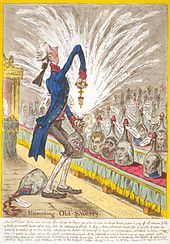

The contemporary satire The Rolliad ridiculed him for his youth:[37] Above the rest, majestically great, Behold the infant Atlas of the state, The matchless miracle of modern days, In whom Britannia to the world displays A sight to make surrounding nations stare; A kingdom trusted to a school-boy's care.

[40] Pitt gained great popularity with the public at large as "Honest Billy" who was seen as a refreshing change from the dishonesty, corruption and lack of principles widely associated with both Fox and North.

Despite a series of defeats in the House of Commons, Pitt defiantly remained in office, watching the Coalition's majority shrink as some Members of Parliament left the Opposition to abstain.

Early returns showed a massive swing to Pitt with the result that many Opposition Members who still had not faced election either defected, stood down, or made deals with their opponents to avoid expensive defeats.

In a contest estimated to have cost a quarter of the total spending in the entire country, Fox bitterly fought against two Pittite candidates to secure one of the two seats for the constituency.

Further augmentations and clarifications of the governor-general's authority were made in 1786, presumably by Lord Sydney, and presumably as a result of the company's setting up of Penang with their own superintendent (governor), Captain Francis Light, in 1786.

[55] During the Nootka Sound Controversy in 1790, Pitt took advantage of the alliance to force Spain to give up its claim to exclusive control over the western coast of North and South America.

In August 1792, coincident with the capture of Louis XVI by the French revolutionaries, George III appointed Pitt as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a position whose incumbent was responsible for the coastal defences of the realm.

In Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey, which was written in the 1790s, but not published until 1817, one of the characters remarks that it is not possible for a family to keep secrets in these modern times when spies for the government were lurking everywhere.

The heavy death toll caused by yellow fever, the much dreaded "black vomit", made conquering St. Domingue impossible, but an undeterred Pitt launched what he called the "great push" in 1795, sending out an even larger British expedition.

Thinking a less sectarian and more conciliatory approach would have avoided the uprising, Pitt sought an Act of Union that would make Ireland an official part of the United Kingdom and end the "Irish Question".

[86] As the Dublin parliament did not wish to disband, Pitt made generous use of what would now be called "pork barrel politics" to bribe Irish MPs to vote for the Act of Union.

[89] Realising that the Catholic church was an ally in the struggle against the French Revolution, Pitt had tried fruitlessly to persuade the Dublin parliament to loosen the anti-Catholic laws to "keep things quiet in Ireland".

[93] In much of rural Ireland, law and order had broken down as an economic crisis further impoverished the already poor Irish peasantry, and a sectarian war with many atrocities on both sides had begun in 1793 between Catholic "Defenders" versus Protestant "Peep o' Day Boys".

[88] A section of the Peep o'Day Boys who had renamed themselves the Loyal Orange Order in September 1795 were fanatically committed to upholding Protestant supremacy in Ireland at "almost any cost".

[88] In December 1796, a French invasion of Ireland led by General Lazare Hoche (scheduled to coordinate with a rising of the United Irishmen) was only thwarted by bad weather.

[88] To crush the United Irishmen, Pitt sent General Lake to Ulster in 1797 to call out Protestant Irish militiamen and organised an intelligence network of spies and informers.

Henry Dundas, who was President of the Board of Control, Treasurer of the Navy, Secretary at War and a close friend of Pitt, envied the First Minister for his ability to sleep well in all crcumstances.

The king was strongly opposed to Catholic emancipation; he argued that to grant additional liberty would violate his coronation oath, in which he had promised to protect the established Church of England.

[96] Shortly after leaving office, Pitt supported the new administration under Addington, but with little enthusiasm; he frequently absented himself from Parliament, preferring to remain in his Lord Warden's residence of Walmer Castle—before 1802 usually spending an annual late-summer holiday there, and later often present from the spring until the autumn.

Pitt's lack of interest in enlarging his social circle meant that it did not grow to encompass any women outside his own family, a fact that produced a good deal of rumour.

From late 1784, a series of satirical verses appeared in The Morning Herald drawing attention to Pitt's lack of knowledge of women: "Tis true, indeed, we oft abuse him,/Because he bends to no man;/But slander's self dares not accuse him/Of stiffness to a woman."