Placoderm

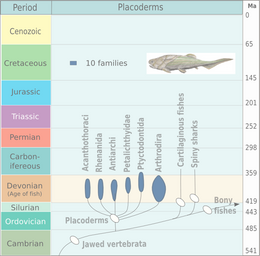

Placoderms (from Ancient Greek πλάξ (plax, plakos) 'plate' and δέρμα (derma) 'skin')[1] are vertebrate animals of the class Placodermi, an extinct group of prehistoric fish known from Paleozoic fossils during the Silurian and the Devonian periods.

While their endoskeletons are mainly cartilaginous, their head and thorax were covered by articulated armoured plates (hence the name), and the rest of the body was scaled or naked depending on the species.

[3] Placoderms are thought to be paraphyletic, consisting of several distinct outgroups or sister taxa to all living jawed vertebrates, which originated among their ranks.

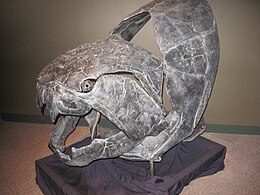

[6] They eventually outcompeted the previously dominant marine arthropods (e.g. eurypterids) and cephalopod molluscs (e.g. orthocones), producing some of the first and most infamous vertebrate apex predators such as Eastmanosteus, Dinichthys and the massive Dunkleosteus.

[2] One of the largest known arthrodires, Dunkleosteus terrelli, was 3.5–4.1 metres (11–13 ft) long,[9] and is presumed to have had a large distribution, as its remains have been found in Europe, North America and possibly Morocco.

Other, smaller arthrodires, such as Fallacosteus and Rolfosteus, both of the Gogo Formation of Western Australia, had streamlined, bullet-shaped head armor, and Amazichthys, with morphology like that of other fast-swimming pelagic organisms,[10] strongly supporting the idea that many, if not most, arthrodires were active swimmers, rather than passive ambush-hunters whose armor practically anchored them to the sea floor.

Extraordinary evidence of internal fertilization in a placoderm was afforded by the discovery in the Gogo Formation, near Fitzroy Crossing, Kimberley, Western Australia,[11] of a small female placoderm, about 25 cm (10 in) in length, which died in the process of giving birth to a 6 cm (2+1⁄2 in) offspring and was fossilized with the umbilical cord intact.

[12] The fossil, named Materpiscis attenboroughi (after scientist David Attenborough), had eggs which were fertilized internally, the mother providing nourishment to the embryo and giving birth to live young.

Specimens of the arthrodire Incisoscutum ritchei, also from the Gogo Formation, have been found with embryos inside them indicating this group also had live bearing ability.

While the claspers in cartilaginous fishes are specialized parts of their paired pelvic fins that have been modified for copulation due to changes in the hox genes hoxd13, the origin of the mating organs in placoderms most likely relied on different sets of hox genes and were structures that developed further down the body as an extra and independent pair of appendages, but which during development turned into body parts used for reproduction only.

With more accurate summaries of prehistoric organisms, it is now thought that they systematically died out as marine and freshwater ecologies suffered from the environmental catastrophes of the Late Devonian and end-Devonian extinctions.

In the late 1920s, Dr. Erik Stensiö, at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, established the details of placoderm anatomy and identified them as true jawed fishes related to sharks.

Once the specimens had been completely ground away (and so destroyed), he made enlarged, three-dimensional models of the skulls to examine the anatomical details more thoroughly.

These orders are considered to be basal or primitive groups within Placodermi, though their precise placement within the class remains unsure.

Arthrodira ("jointed neck") were the most diverse and numerically successful of the placoderm orders, occupying roles from giant apex predators to detritus-nibbling bottom dwellers.

The largest member of this group, Dunkleosteus, was a true "superpredator" of the latest Devonian period, reaching 3 to as much as 8 metres in length.

Fossils of Incisoscutum have been found containing unborn fetuses, indicating that arthrodires gave birth to live young.

Rhenanida ("Rhine fish") were flattened, ray-like, bottom-dwelling predators with large, upturned mouths that lived in marine environments.

From what can be inferred from the mouthplates of fossil specimens, acanthothoracids were shellfish hunters ecologically similar to modern-day chimaeras.

Petalichthyida ("thin-plated fish") were small, flattened placoderms, typified by their splayed fins and numerous tubercles that decorated all of the plates and scales of their armour.

There was an independent diversification event that occurred in what is now Southern China, producing a handful of unique genera that were once placed in their own order, "Quasipetalichthyida", named after the first discovered species there, Quasipetalichthys haikouensis.

As such, placoderm experts consider Pseudopetalichthyida to be the sister group of the Arthrodires + Phyllolepida + Antiarchi trichotomy and the Acanthothoraci + Rhenanida dichotomy.

Stensioellida ("[Heintz's] little Stensio") contains another problematic placoderm of uncertain affinity, known only from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück slates of Germany.

Critics of Janvier's position say that aside from a bodyplan superficially similar to primitive holocephalians, the two groups have little else in common anatomically.

The following cladogram shows the interrelationships of placoderms according to Carr et al. (2009):[27] Stensioella Pseudopetalichthys Brindabellaspis Acanthothoraci Rhenanida Yunnanolepis Euantiarcha Petalichthyida Ptyctodontida Wuttagoonaspis Actinolepidae Phyllolepida Phlyctaeniida Holonema Antineosteus Buchanosteidae Pholidosteus Tapinosteus Coccosteus Torosteus Plourdosteus Dunkleosteus Brachyosteus Erromenosteus Gorgonichthys Titanichthys However, the cladogram had changed significantly over the years, and the placoderms are now thought to be paraphyletic,[28] with some being more closer to the Eugnathostomata than others.

The updated cladogram (Zhu et al., 2016):[29] Cephalaspidomorphi Antiarchi Petalichthyida Arthrodira Ptyctodontida Qilinyu Entelognathus Janusiscus Chondrichthyes (total group, including Acanthodii as stem lineages) Osteichthyes