Atmospheric escape

The relative importance of each loss process depends on the planet's escape velocity, its atmosphere composition, and its distance from its star.

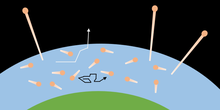

Individual molecules in the high tail of the distribution (where a few particles have much higher speeds than the average) may reach escape velocity and leave the atmosphere, provided they can escape before undergoing another collision; this happens predominantly in the exosphere, where the mean free path is comparable in length to the pressure scale height.

The number of particles able to escape depends on the molecular concentration at the exobase, which is limited by diffusion through the thermosphere.

This is why the gas giant planets still retain significant amounts of hydrogen, which escape more readily from Earth's atmosphere.

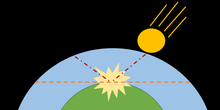

In this case, a large amount of thermal energy, usually through extreme ultraviolet radiation, is absorbed by the atmosphere.

[3] Hydrodynamic escape has been observed for exoplanets close to their host star, including the hot Jupiter HD 209458b.

This type of interaction is more pronounced in the absence of a planetary magnetosphere, as the electrically charged solar wind is deflected by magnetic fields, which mitigates the loss of atmosphere.

Near the poles of a magnetosphere, the magnetic field lines are open, allowing a pathway for ions in the atmosphere to exhaust into space.

If a collision is sufficiently energetic, it is possible for ejecta, including atmospheric molecules, to reach escape velocity.

[10] In order to have a significant effect on atmospheric escape, the radius of the impacting body must be larger than the scale height.

[1] A Japanese research team in 2017 found evidence of a small number of oxygen ions on the moon that came from the Earth.

[11] In 1 billion years, the Sun will be 10% brighter than it is now, making it hot enough on Earth to dramatically increase the water vapor in the atmosphere where solar ultraviolet light will dissociate H2O, allowing it to gradually escape into space until the oceans dry up[12]: 159 Recent models indicate that hydrogen escape on Venus is almost entirely due to suprathermal mechanisms, primarily photochemical reactions and charge exchange with the solar wind.

[13] Venus Express measured the effect of coronal mass ejections on the rate of atmospheric escape of Venus, and researchers found a factor of 1.9 increase in escape rate during periods of increased coronal mass ejections compared with calmer space weather.

[14] Primordial Mars also suffered from the cumulative effects of multiple small impact erosion events,[15] and recent observations with MAVEN suggest that 66% of the 36Ar in the Martian atmosphere has been lost over the last 4 billion years due to suprathermal escape, and the amount of CO2 lost over the same time period is around 0.5 bar or more.

[17] Jeans escape of hydrogen can be significantly modulated by lower atmospheric processes, such as gravity waves, convection, and dust storms.

Other heavy atoms, such as carbon and nitrogen, are primarily lost due to photochemical reactions and interactions with the solar wind.

However Titan spends roughly half of its orbital period outside of the bow-shock, subjected to unimpeded solar winds.

In 2018 it was discovered with the Hubble Space Telescope that atmospheric escape can also be measured with the 1083 nm Helium triplet.

Helium has on the other hand the disadvantage that it requires knowledge about the hydrogen-helium ratio to model the mass-loss of the atmosphere.