Plant evolutionary developmental biology

[2] Most of the synthesis in evo-devo has been in the field of animal evolution, one reason being the presence of model systems like Drosophila melanogaster, C. elegans, zebrafish and Xenopus laevis.

Nehemiah Grew, Marcello Malpighi, Robert Hooke, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Wilhelm von Nageli were just some of the people who helped build knowledge on plant morphology at various levels of organisation.

Availability of complete physical and genetic maps,[16] RNAi vectors, and rapid transformation protocols are some of the technologies that have significantly altered the scope of the field.

[15] Recently, there has also been a massive increase in the genome and EST sequences[17] of various non-model species, which, coupled with the bioinformatics tools existing today, generate opportunities in the field of plant evo-devo research.

[29] The Cycad Genomics Project,[30] for example, aims to understand the differences in structure and function of genes between gymnosperms and angiosperms through sampling in the order Cycadales.

Apart from EST and genome sequences, several other tools like PCR, yeast two-hybrid system, microarrays, RNA Interference, SAGE, QTL mapping etc.

Recently, cross-species hybridization has begun to be employed on microarray chips, to study the conservation and divergence in mRNA expression patterns between closely related species.

These began to diversify in the late Silurian period, around 420 million years ago, and the fruits of their diversification are displayed in remarkable detail in an early Devonian fossil assemblage known as the Rhynie chert.

The grasses, as well as many other groups, evolved new mechanisms of metabolism to survive the low CO2 and warm, dry conditions of the tropics over the last 10 million years.

[39] Megaphylls, according to the telome theory, have evolved from plants that showed a three-dimensional branching architecture, through three transformations: planation, which involved formation of a planar architecture, webbing, or formation of the outgrowths between the planar branches and fusion, where these webbed outgrowths fused to form a proper leaf lamina.

Today's megaphyll leaves probably became commonplace some 360 mya, about 40 my after the simple leafless plants had colonized the land in the early Devonian period.

This spread has been linked to the fall in the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations in the late Paleozoic era associated with a rise in density of stomata on leaf surface.

Large leaves with less stomata would have heated up in the sun's rays, but an increased stomatal density allowed for a better-cooled leaf, thus making its spread feasible.

Similarly, trees that grow in temperate or taiga regions have pointed leaves, presumably to prevent nucleation of ice onto the leaf surface and reduce water loss due to transpiration.

Herbivory, not only by large mammals, but also small insects has been implicated as a driving force in leaf evolution, an example being plants of the genus Aciphylla, that are commonly found in New Zealand.

[57] The flowering plants have long been assumed to have evolved from within the gymnosperms; according to the traditional morphological view, they are closely allied to the gnetales.

A flower can be considered a powerful evolutionary innovation, because its presence allowed the plant world to access new means and mechanisms for reproduction.

[57][65] Arabidopsis thaliana has a gene called AGAMOUS that plays an important role in defining how many petals and sepals and other organs are generated.

Researchers have found that the morphology of these flowers is because of strong mutations in the AGAMOUS homolog in these plants, which leads to them making a large number of petals and sepals.

For example, Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes that grow in the cold temperate regions require prolonged vernalization before they flower, while the tropical varieties and common lab strains, do not.

Molecular clock analysis has shown that the other LFY paralog was lost in angiosperms around the same time as flower fossils become abundant, suggesting that this event might have led to floral evolution.

In 1878 Charles Darwin published a book “The Effects of Cross and Self-Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom”[72] and in the initial paragraph of chapter XII noted "The first and most important of the conclusions which may be drawn from the observations given in this volume, is that generally cross-fertilisation is beneficial and self-fertilisation often injurious, at least with the plants on which I experimented."

Flowers likely emerged in plant evolution as an adaptation to facilitate cross-fertilisation (outcrossing), a process that allows the masking of recessive deleterious mutations in the genome of progeny.

Also, meiosis, the process in flowering plants by which seed progeny are produced, provides a direct mechanism for repairing germ-line DNA through genetic recombination.

[74] Thus, in flowering plants, the two fundamental aspects of sexual reproduction are cross-fertilization (outcrossing) and meiosis and these appear to be maintained respectively by the advantages of genetic complementation and recombinational repair of germline DNA.

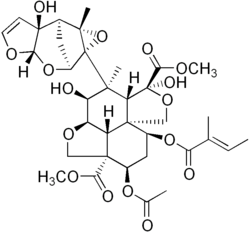

[73] Plant secondary metabolites are low molecular weight compounds, sometimes with complex structures that have no essential role in primary metabolism.

They function in processes such as anti-herbivory, pollinator attraction, communication between plants, allelopathy, maintenance of symbiotic associations with soil flora and enhancing the rate of fertilization[how?].

[75] Many plant secondary metabolites such as the colour and flavor components of saffron and the chemotherapeutic drug taxol are of culinary and medical significance to humans and are therefore of commercial importance.

[citation needed] Cyanogenic glycosides may have been proposed to have evolved multiple times in different plant lineages, and there are several other instances of convergent evolution.

Teosinte belongs to the genus Zea, just as maize, but bears very small inflorescence, 5–10 hard cobs, and a highly branched and spread-out stem.