Platecarpus

[3] Isotopic analysis on teeth specimens has suggested that this genus and Clidastes may have entered freshwater occasionally, just like modern sea snakes.

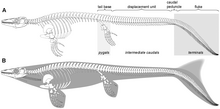

[4] Platecarpus had a long, down-turned tail with a large dorsal lobe on it, steering flippers, and jaws lined with conical teeth.

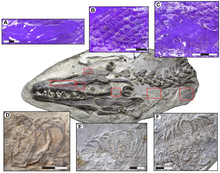

Small structures in the retina, each around 2 μm long and observed by scanning electron microspectroscopy, may represent retinal melanosomes preserved in their original positions.

The scales on the snout indicate that the nostrils were placed far in front of the skull at its tip and faced laterally as in most squamates and archosaurs.

The body scales are all rhomboidal in shape and form tightly connecting diagonal rows that overlap each other at their posterior edges.

The reddish areas were analysed with mass spectrometry and were shown to contain high levels of compounds made of iron and porphyrin.

Coprolites from the mosasaur Globidens are also suggestive of low digestion and absorption rates as they contain masses of crushed bivalve shells.

[5] Platecarpus fossils have been found in rocks that date back to the late Santonian through the early Campanian in the Smoky Hill Chalk.

[8] In 2011, a new generic name, Plesioplatecarpus, was erected by Takuya Konishi and Michael W. Caldwell to incorporate P. planifrons, which they found was distinct from Platecarpus in a phylogenetic analysis.

[9] Clidastes propython Kourisodon puntledgensis Yaguarasaurus columbianus Russellosaurus coheni Tethysaurus nopcsai Tylosaurus kansasensis Tylosaurus proriger Ectenosaurus clidastoides Angolasaurus bocagei Selmasaurus johnsoni Selmasaurus russelli Plesioplatecarpus planifrons Platecarpus tympaniticus Latoplatecarpus willistoni Latoplatecarpus nichollsae Platecarpus somenensis Plioplatecarpus primaevus Plioplatecarpus houzeaui Plioplatecarpus marshi Compared to the tylosaurs, plioplatecarpine mosasaurs had much less robust teeth, suggesting that they fed on smaller (or softer) prey such as small fish and squid.

[5] While mosasaurs are traditionally thought to have propelled themselves through the water by lateral undulation in a similar way to eels, the deep caudal fin of Platecarpus suggests that it swam more like a shark.

The neural spines of these vertebrae also have grooves for the insertion of interspinal ligaments and dorsal connective tissues which would have aided in lateral movement of the fluke.

The ligaments were probably made of collagenous fibers that acted as springs to move the tail back into a resting position after energy was stored in them.

The early mosasauroid Vallecillosaurus also preserves body scales, but they are larger and more varied in shape, suggesting that the animal relied on undulatory movement in its trunk rather than just its tail.

Plotosaurus, a more derived mosasaur than Platecarpus, has even smaller scales covering its body, indicating that it had even more efficient locomotion in the water.