Poetic diary

Traditionally, composed of a series of poems held together by prose sections, the poetic diary has often taken the form of a pillow book or a travel journal.

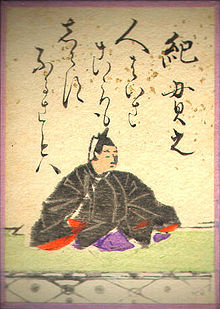

Departing from the tradition of diaries written in Chinese, Tsurayuki used vernacular Japanese characters, waka poetry, and a female narrator to convey the emotional aspects of the journey.

[1] However, three major characteristics of Japanese diary literature, though exceptions abound, are "the frequent use of poems, breaking away from the daily entry as a formal device, and a stylistic heightening.

5 For example, in writing her Kagero Nikki, Mother of Michitsuna claims a motive “to answer, should anyone ask, what is it like, the life of a woman married to a highly placed man?”4 Heian nikki in particular, according to scholar Haruo Shirane, are united in “the fact that they all depict the personal life of a historical personage.”[4] Thematically, many diaries lay heavy emphasis on time and poetry.

[5] More than just developing from a poetic tradition, "it seems clear that poetry is conceived of as the most basic or purest literary form and that its presence, almost alone, is enough to change a journal of one’s life into an art diary.

[3] Starting a tradition of psychological exploration and self-expression through Japanese vernacular, nikki bungaku not only gives modern readers an idea of historical events but also a view into the lives and minds of their authors.

Literary diaries are also believed to have influenced Murasaki Shikibu's classic Genji Monogatari, arguably the first and one of the greatest court novels of all time.

Lastly, though the definition is disputable, one can argue that the Japanese literary diary tradition continues to the present and remains an important element of culture and personal expression.