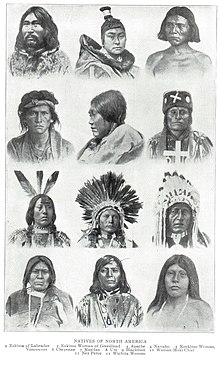

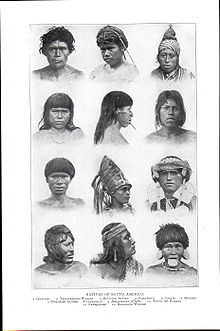

Population history of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

[1][2] The monarchs of the nascent Spanish Empire decided to fund Christopher Columbus' voyage in 1492, leading to the establishment of colonies and marking the beginning of the migration of millions of Europeans and Africans to the Americas.

There are numerous reasons for the population decline, including exposure to Eurasian diseases such as influenza, pneumonic plagues, and smallpox; direct violence by settlers and their allies through war and forced removal; and the general disruption of societies.

[27] Roland G Robertson suggests that during the late 1630s, smallpox killed over half of the Wyandot (Huron), who controlled most of the early North American fur trade in the area of New France.

Historian Francis Jennings argued, "Scholarly wisdom long held that Indians were so inferior in mind and works that they could not possibly have created or sustained large populations.

[120] The overall pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were recently colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70–250), and then they grew by a factor of 10 over 800–1,000 years.

[127] The most notable account was that of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whose writings vividly depict Spanish atrocities committed in particular against the Taínos.

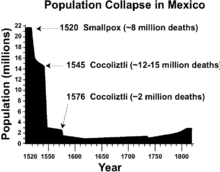

Scholars like Cook believe that widespread epidemic disease, to which the Indigenous peoples had no prior exposure or resistance, was the primary cause of the massive population decline of the Native Americans.

[131] However, recently scholars have studied the link between physical colonial violence such as warfare, displacement, and enslavement, and the proliferation of disease among Native populations.

[4][132][133] For example, according to Coquille scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker, "In recent decades, however, researchers challenge the idea that disease is solely responsible for the rapid Indigenous population decline.

[136] In this way, "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the Indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, as it set the conditions for diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and malaria to flourish.

[135] Similarly, historian Jeffrey Ostler at the University of Oregon has argued that population collapses in North America throughout colonization were not due mainly to lack of Native immunity to European disease.

Further, in relation to British colonization in the Northeast, Algonquian speaking tribes in Virginia and Maryland "suffered from a variety of diseases, including malaria, typhus, and possibly smallpox."

[137] He also wrote:[138] ...Despite frequent undocumented assertions that disease was responsible for the great majority of indigenous deaths in the Americas, there does not exist a single scholarly work that even pretends to demonstrate this claim on the basis of solid evidence.

The supposed truism that more native people died from disease than from direct face-to-face killing or from gross mistreatment or other concomitant derivatives of that brutality such as starvation, exposure, exhaustion, or despair is nothing more than a scholarly article of faith...In contrast, historian Russel Thornton has pointed out that there were disastrous epidemics and population losses during the first half of the sixteenth century "resulting from incidental contact, or even without direct contact, as disease spread from one American Indian tribe to another.

"[140] The European colonization of the Americas resulted in the deaths of so many people it contributed to climatic change and temporary global cooling, according to scientists from University College London.

[143] According to one of the researchers, UCL Geography Professor Mark Maslin, the large death toll also boosted the economies of Europe: "the depopulation of the Americas may have inadvertently allowed the Europeans to dominate the world.

"[144] When Old World diseases were first carried to the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, they spread throughout the southern and northern hemispheres, leaving the Indigenous populations in near ruins.

[131][145] No evidence has been discovered that the earliest Spanish colonists and missionaries deliberately attempted to infect the American Natives, and some efforts were made to limit the devastating effects of disease before it killed off what remained of their labor force (compelled to work under the encomienda system).

Well-documented accounts of incidents involving both threats and acts of deliberate infection are very rare, but may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged.

[150][151] Artist and writer George Catlin observed that Native Americans were also suspicious of vaccination, "They see white men urging the operation so earnestly they decide that it must be some new mode or trick of the pale face by which they hope to gain some new advantage over them.

"[152] So great was the distrust of the settlers that the Mandan chief Four Bears denounced the white man, whom he had previously treated as brothers, for deliberately bringing the disease to his people.

[148][156][157] In the following weeks, Sir Jeffrey Amherst conspired with Bouquet to "Extirpate this Execreble Race" of Native Americans, writing, "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians?

Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences.

"[154] However, some sources attribute the 1836–40 epidemic to the deliberate communication of smallpox to Native Americans, with historian Ann F. Ramenofsky writing, "Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets.

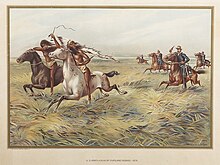

[162] Across the western hemisphere, war with various Native American civilizations constituted alliances based out of both necessity or economic prosperity and, resulted in mass-scale intertribal warfare.

[168] According to Adam Jones, genocidal methods included the following: Some Spaniards objected to the encomienda system of labor, notably Bartolomé de las Casas, who insisted that the Indigenous people were humans with souls and rights.

The infamous Bandeirantes from São Paulo, adventurers mostly of mixed Portuguese and Native ancestry, penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves.

[172] Historian Andrés Reséndez argues that even though the Spanish were aware of the spread of smallpox, they made no mention of it until 1519, a quarter century after Columbus arrived in Hispaniola.

According to Ostler, "by 1860, their numbers had been cut in half" because of low fertility, high infant mortality, and increased disease caused by conditions such as polluted drinking water, few resources, and social stress.

"[182] On 8 September 2000, the head of the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) formally apologized for the agency's participation in the ethnic cleansing of Western tribes.