Prostitution in ancient Greece

[note 1] In the more important cities, and particularly the many ports, it employed a significant number of people and represented a notable part of economic activity.

This owner could be a citizen, for this activity was considered as a source of income just like any other: one 4th-century BC orator cites two; Theophrastus in Characters (6:5) lists pimp next to cook, innkeeper, and tax collector as an ordinary profession, though disreputable.

The poet Philemon praised him for this measure in the following terms: [Solon], seeing Athens full of young men, with both an instinctual compulsion, and a habit of straying in an inappropriate direction, bought women and established them in various places, equipped and common to all.

Besides directly displaying their charms to potential clients they had recourse to publicity; sandals with marked soles have been found which left an imprint that stated ΑΚΟΛΟΥΘΕΙ AKOLOUTHEI ("Follow me") on the ground.

Eubulus, a comic author, offers these courtesans derision: "plastered over with layers of white lead, … jowls smeared with mulberry juice.

And if you go out on a summer's day, two rills of inky water flow from your eyes, and the sweat rolling from your cheeks upon your throat makes a vermilion furrow, while the hairs blown about on your faces look grey, they are so full of white lead".

[6] These prostitutes had various origins: Metic women who could not find other work, poor widows, and older pornai who had succeeded in buying back their freedom (often on credit).

[10] In the 1st century BC, the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, cited in the Palatine anthology, V 126, mentions a system of subscription of up to five drachma for a dozen visits.

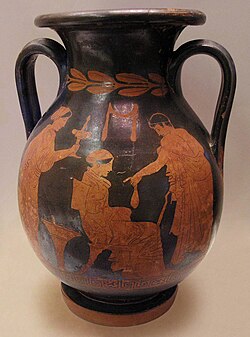

A young and pretty prostitute could charge a higher price than her in-decline colleague; even if, as iconography on ceramics demonstrates, a specific market existed for older women.

(The story goes of a hetaira being reproached by a woman for not loving her job and not touching wool,[note 4] and answering her: 'However you may behold me, yet in this short time I have already taken down three pieces'.

Remarks elsewhere of Strabo (XII,3,36: "women earning money with their bodies") as well as Athenaeus (XIII,574: "in the lovely beds picking the fruits of the mildest bloom") concerning this temple describe this character even more graphically.

In 464 BC, a man named Xenophon, a citizen of Corinth who was an acclaimed runner and winner of pentathlon at the Olympic Games, dedicated one hundred young girls to the temple of the goddess as a sign of thanksgiving.

[19] The work of gender researchers like Daniel Arnaud,[20] Julia Assante[21] and Stephanie Budin[22] has cast the whole tradition of scholarship that defined the concept of sacred prostitution into doubt.

Budin regards the concept of sacred prostitution as a myth, arguing taxatively that the practices described in the sources were misunderstandings of either non-remunerated ritual sex or non-sexual religious ceremonies, possibly even mere cultural slander.

[25] In archaic and classical Sparta, Plutarch claims that there were no prostitutes due to the lack of precious metals and money, and the strict moral regime introduced by Lycurgus.

One of the many slang terms for prostitutes was khamaitypếs (χαμαιτυπής) 'one who hits the ground', suggesting to some literal-minded commentators that their activities took place in the dirt or possibly on all fours from behind.

Given the Ancient Greeks' propensity for poetic thinking, it seems just as likely that this term also suggested that there is 'nothing lower', rather than that a significant proportion of prostitutes were reduced to plying their trade in the mud.

[citation needed] Certain authors have prostitutes talking about themselves: Lucian in his Dialogue of courtesans or Alciphron in his collection of letters; but these are works of fiction.

Nevertheless, in a treatise attributed to Hippocrates (Of the Seed, 13), he describes in detail the case of a dancer "who had the habit of going with the men"; he recommends that she "jump up and down, touching her buttocks with her heels at each leap"[30] to dislodge the sperm, and thus avoid risk.

[32] Finally, a number of vases represent scenes of abuse, where the prostitute is threatened with a stick or sandal, and forced to perform acts considered by the Greeks to be degrading: fellatio, sodomy or sex with multiple partners.

[citation needed] Naeara, whose career is described in a legal discourse, manages to raise three children before her past as a hetaera catches up to her.

Ovid, in his Amores, states "Whil'st Slaves be false, Fathers hard, and Bauds be whorish, Whilst Harlots flatter, shall Menander flourish.

Menander also created, contrary to the traditional image of the greedy prostitute, the part of the "whore with a heart of gold" in Dyskolos, where this permits a happy conclusion to the play.

In a different genre, Plato, in the Republic, proscribed Corinthian prostitutes in the same way as Attican pastries, both being accused of introducing luxury and discord into the ideal city.

The cynic Crates of Thebes, (cited by Diodorus Siculus, II, 55–60) during the Hellenistic period describes a utopian city where, following the example of Plato, prostitution is also banished.

[35]" The period during which adolescents were judged as desirable extended from puberty until the appearance of a beard, the hairlessness of youth being an object of marked taste among the Greeks.

If some portions of society did not have the time or means to practice the interconnected aristocratic rituals (spectating at the gymnasium, courtship, gifting),[note 7] they could all satisfy their desires with prostitutes.

Conversely, prostituting an adolescent, or offering him money for favours, was strictly forbidden as it could lead to the youth's future loss of legal status.

The Greek reasoning is explained by Aeschines (stanza 29), as he cites the dokimasia (δοκιμασία): the citizen who prostituted himself (πεπορνευμένος peporneuménos) or causes himself to be so maintained (ἡταιρηκώς hētairēkós) is deprived of making public statements because "he who has sold his own body for the pleasure of others (ἐφ’ ὕβρει eph’ hybrei) would not hesitate to sell the interests of the community as a whole".

In the forensic speech Against Simon, the prosecutor claimed to have hired a boy's sexual services for the price of 300 drachma, much more than what "middle range" hetaira typically charged.