Portuguese phonology

The phonology of Portuguese varies among dialects, in extreme cases leading to some difficulties in mutual intelligibility.

[citation needed] The medieval Galician-Portuguese system of seven sibilants (/ts dz/, /ʃ ʒ/, /tʃ/, and apicoalveolar /s̺ z̺/) is still distinguished in spelling (intervocalic c/ç z, x g/j, ch, ss -s- respectively), but is reduced to the four fricatives /s z ʃ ʒ/ by the merger of /tʃ/ into /ʃ/ and apicoalveolar /s̺ z̺/ into either /s z/ or /ʃ ʒ/ (depending on dialect and syllable position), except in parts of northern Portugal (most notably in the Trás-os-Montes region).

Phonetic notes There is a variation in the pronunciation of the first consonant of certain clusters, most commonly C or P in cç, ct, pç and pt.

[16] In most cases, Brazilians variably conserve the consonant while speakers elsewhere have invariably ceased to pronounce it (for example, detector in Brazil versus detetor in Portugal).

Câmara (1953) and Mateus & d'Andrade (2000) see the soft as the unmarked realization and that instances of intervocalic [ʁ] result from gemination and a subsequent deletion rule (i.e., carro /ˈkaro/ > [ˈkaɾʁu] > [ˈkaʁu]).

For example, an alveolar trill [r] is found in certain conservative dialects down São Paulo, of Italian-speaking, Spanish-speaking, Arabic-speaking, or Slavic-speaking influence.

A uvular trill [ʀ] is found in areas of German-speaking, French-speaking, and Portuguese-descended influence throughout coastal Brazil down Espírito Santo, most prominently Rio de Janeiro.

[26] Evidence of this allophone is often encountered in writing that attempts to approximate the speech of communities with this pronunciation, e.g., the rhymes in the popular poetry (cordel literature) of the Northeast and phonetic spellings (e.g., amá, sofrê in place of amar, sofrer) in Jorge Amado's novels (set in the Northeast) and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri's play Eles não usam black tie (about favela dwellers in Rio de Janeiro).

[27][28] The soft realization is often maintained across word boundaries in close syntactic contexts (e.g., mar azul [ˈmaɾ aˈzuw] 'blue sea').

[32] In central European Portuguese this contrast occurs in a limited morphological context, namely in verb conjugation between the first person plural present and past perfect indicative forms of verbs such as pensamos ('we think') and pensámos ('we thought'; spelled ⟨pensamos⟩ in Brazil).

In Brazilian Portuguese, they are raised to close /i, u/ after a stressed syllable,[34] or in some accents and in general casual speech, also before it.

[40] European Portuguese possesses a near-close near-back unrounded vowel, transcribed /ɨ/ in this article.

[46][47] In these and other cases, other diphthongs, diphthong-hiatus or hiatus-diphthong combinations might exist depending on speaker, such as [uw] or even [uw.wu] for suo ('I sweat'), and in BP [ij] or even [ij.ji] for fatie ('slice it').

At least in European Portuguese, the diphthongs [ɛj, aj, ɐj, ɔj, oj, uj, iw, ew, ɛw, aw] tend to have more central second elements [ɛɪ̯, aɪ̯, ʌɪ̯, ɔɪ̯, oɪ̯, uɪ̯, iʊ̯, eʊ̯, ɛʊ̯, aʊ̯] (as stated above, the starting point of /ɐi/ is typically back) – note that [ʊ̯] is also more weakly rounded than the [u] monophthong.

Cruz-Ferreira (1995) analyzes European Portuguese with five monophthongs and five diphthongs, all phonemic: /ĩ ẽ ɐ̃ õ ũ ɐ̃j̃ õj̃ ũj̃ ɐ̃w̃ õw̃/.

consider them to be a result of external influences, including the common language spoken at Brazil's coast at time of the European arrival, Tupi.

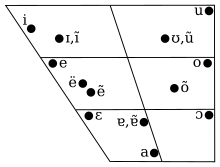

[14] The stressed relatively open vowels /a, ɛ, ɔ/ contrast with the stressed relatively close vowels /ɐ, e, o/ in several kinds of grammatically meaningful alternation: There are also pairs of unrelated words that differ in the height of these vowels, such as besta /e/ ('beast') and besta /ɛ/ ('crossbow'); mexo /e/ ('I move') and mecho /ɛ/ ('I highlight [hair]'); molho /o/ ('sauce') and molho /ɔ/ ('bunch'); corte /ɔ/ ('cut') and corte /o/ ('court'); meta /e/ ('I put' subjunctive) and meta /ɛ/ ('goal'); and (especially in Portugal) para /ɐ/ ('for') and para /a/ ('he stops'); forma /o/ ('mold') and forma /ɔ/ ('shape').

There are several minimal pairs in which a clitic containing the vowel /ɐ/ contrasts with a monosyllabic stressed word containing /a/: da vs. dá, mas vs. más, a vs. à /a/, etc.

Some isolated vowels (meaning those that are neither nasal nor part of a diphthong) tend to change quality in a fairly predictable way when they become unstressed.

In Brazilian Portuguese, the general pattern in the southern and western accents is that the stressed vowels /a, ɐ/, /e, ɛ/, /o, ɔ/ neutralize to /a/, /e/, /o/, respectively, in unstressed syllables, as is common in Romance languages.

For example, /i/ occurs instead of unstressed /e/ or /ɨ/, word-initially or before another vowel in hiatus (teatro, reúne, peão).

[58] Some examples: flagrante /flɐˈɡɾɐ̃tɨ/, complexo /kõˈplɛksu/, fixo /ˈfiksu/ (but not ficção /fikˈsɐ̃w/), latex /ˈlatɛks/, quatro /ˈkʷatɾu/, guaxinim /ɡʷɐʃiˈnĩ/, /ɡʷaʃiˈnĩ/ When two words belonging to the same phrase are pronounced together, or two morphemes are joined in a word, the last sound in the first may be affected by the first sound of the next (sandhi), either coalescing with it, or becoming shorter (a semivowel), or being deleted.

As was mentioned above, the dialects of Portuguese can be divided into two groups, according to whether syllable-final sibilants are pronounced as postalveolar consonants /ʃ/, /ʒ/ or as alveolar /s/, /z/.

This applies also to words that are pronounced together in connected speech: Normally, only the three vowels /ɐ/, /i/ (in BP) or /ɨ/ (in EP), and /u/ occur in unstressed final position.

Thus, If the next word begins with a dissimilar vowel, then /i/ and /u/ become approximants in Brazilian Portuguese (synaeresis): In careful speech and in with certain function words, or in some phrase stress conditions (see Mateus and d'Andrade, for details), European Portuguese has a similar process: But in other prosodic conditions, and in relaxed pronunciation, EP simply drops final unstressed /ɨ/ and /u/ (elision), though this is subject to significant dialectal variation: Aside from historical set contractions formed by prepositions plus determiners or pronouns, like à/dà, ao/do, nesse, dele, etc., on one hand and combined clitic pronouns such as mo/ma/mos/mas (it/him/her/them to/for me), and so on, on the other, Portuguese spelling does not reflect vowel sandhi.

The orthography of Portuguese takes advantage of this correlation to minimize the number of diacritics, but orthographic rules vary in different regions (e.g., Brazil and Portugal), and should not be used as a reliable guide to stress, despite the existing correlations found in the grapheme-phoneme conversion of Portuguese data.

For example, regardless of which verb one considers, stress is always final for the first person singular in the future simple tense (indicative): (eu) falarei 'I will speak'.

All other patterns are considered to be irregular in most approaches in the literature, even though subregularities have been determined and discussed in recent studies.

As in most Romance languages, interrogation on yes–no questions is expressed mainly by sharply raising the tone at the end of the sentence.

As for prosodic domains, the presence of metrical feet in Portuguese has been called into question in a recent study, which argues that no strong evidence exists in the language that supports this particular domain (at least Brazilian Portuguese)—despite the presence of stress and secondary stress, both of which are typically (albeit not always) associated with feet.