A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

[3] To carry out an order received in his youth from his spiritual teacher to spread "Krishna consciousness" in English, in his old age, at 69, he journeyed in 1965 from Kolkata to New York City on a cargo ship, taking with him little more than a few trunks of books.

As part of these practices, Prabhupada required that his initiated students strictly refrain from non-vegetarian food (such as meat, fish, or eggs), gambling, intoxicants (including coffee, tea, or cigarettes), and extramarital sex.

[4][5][6] Decades after his death, Prabhupada's teachings and the Society he established continue to be influential,[7] with some scholars and Indian political leaders calling him one of the most successful propagators of Hinduism abroad.

[12][22] In 1922, while still in college, Abhay was persuaded by a friend, Narendranath Mullik,[17] to meet with Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati (1874–1937), a Vaishnava scholar and teacher and the founder of the Gaudiya Math, a spiritual institution for spreading the teachings of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

[50][51] In 1950, A. C. Bhaktivedanta accepted the vanaprastha ashram (the traditional retired order of life), and went to live in Vrindavan, regarded as the site of Krishna's Lila (divine pastimes),[32] although he occasionally commuted to Delhi.

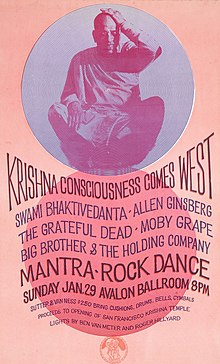

[102] Later that year, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s followers organized San Francisco’s first Ratha Yatra, the festival he had celebrated as a child in imitation of the massive parade held annually in the Indian city of Puri.

[107][91] Also in 1970, Harrison sponsored the publishing of the first volume of Prabhupada’s book Kṛṣṇa, the Supreme Personality of Godhead,[106][112] which related the activities of Krishna's life as told in the tenth canto of the Srimad-Bhagavatam.

On one notable occasion in Nairobi, when he was scheduled to do a program at an Indian Radha-Krishna temple in a mainly African area downtown, he ordered the doors opened to invite the local residents.

[119] During his five days in Moscow, Prabhupada managed to meet only two Soviet citizens: Grigory Kotovsky, a professor of Indian and South Asian studies, and Anatoly Pinyaev, a twenty-three-year-old Muscovite.

[123] He came back to India with a party of Western disciples[62] — ten American sannyasis and twenty other devotees[106] — and for the next seven years focused much of his effort on establishing temples in Bombay, Vrindavan, Hyderabad, and a planned international headquarters in Mayapur, West Bengal (the birthplace of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu).

[148] Prabhupada’s extensive commentaries on the sacred texts follow those of Bhaktisiddhanta, Bhaktivinoda, and other traditional teachers, such as Baladeva Vidyabhushana, Vishvanatha Chakravarti, Jiva Goswami, Madhvacharya, and Ramanujacharya.

That Absolute Truth, he taught, is realized in three phases: as Brahman (all-pervading impersonal oneness), as Paramatma (the aspect of God present within the heart of every living being), and as Bhagavan, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

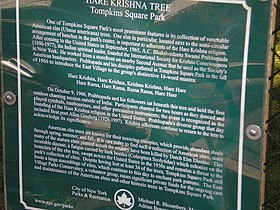

[185] Following Chaitanya, who challenged the caste system and undercut hierarchical power structures,[186] Prabhupada taught that anyone could take to the practice of bhakti-yoga and become self-realized through the chanting of God’s holy names, as found in the Hare Krishna maha-mantra.

[237] The celebrated traditional commentator Shankara wrote, “One who is eager to rid himself of the suffering and delusion of saṁsāra, created by ignorance, and attain Supreme Bliss is entitled to read this Upaniṣad”.

[252] Between 1973 and 1977, Prabhupada’s followers distributed several million books and other pieces of Krishna conscious literature every year in shopping malls, airports, and other public locations in the United States and worldwide.

[269] And “he also goes beyond specific texts and the Gītā itself when he makes it the occasion for the inculcation of a Vaishnava lifestyle,”[264] typified by chanting the maha-mantra, regulating one’s sexual activity, offering food to Krishna, and following a vegetarian diet.

[272] “The position that is attacked with the most regularity and vigor is that of Advaita Vedanta,”[272] “the system of thought that is commonly used to provide the structure for Western understandings of ‘Hinduism’”,[177] whose advocates Prabhupada calls Mayavadins, impersonalists, or monists.

He had to train disciples unaccustomed to Vaishnava culture and philosophy and engage them in furthering his Hare Krishna movement;[280] he had to set up and then guide his Governing Body Commission to see to ISKCON's global management.

As Bryant and Ekstrand comment, “Questionable fund-raising tactics, confrontational attitudes to mainstream authorities, and an isolationist mentality, coupled with the excesses of neophyte proselytizing zeal, brought public disapproval”[131] — something that Prabhupada had to deal with too.

[300][n][non-primary source needed] While working to establish his movement, Prabhupada had to deal with problems caused even by leading disciples, who, monks or not, could still hold on to intellectual baggage, disdain for authority, and ambitions for power.

[303][304][4][o] "In a traditional Hindu vein”,[6] Prabhupada spoke favorably of the myth of Aryan bloodlines and compared darker races to shudras [people of low caste], thus implying them being inferior to the lighter-complexioned humans.

[6] In a recorded room conversation with disciples in 1977, he calls African Americans "uncultured and drunkards", further stating that after being given freedom and equal rights, they caused a disturbance in the society.

[312] Describing her perspective about ISKCON as that of an “outsider” and a “western feminist”,[312] she highlights Prabhupada's firm belief that "bhakti-yoga", the path of Krishna Consciousness, allows transcendence beyond gender distinctions.

[318][319] Similarly, scholar of religion Akshay Gupta observes that Prabhupada did not regard his black disciples as lower or "untouchables",[320] displaying to some of them the same or even greater degree of affection than to his followers of other ethnicities.

[320][p] Another scholar of religion Mans Broo adds that when Prabhupada speaks about castes, he referred to an envisioned “ideal society” in which people would be divided into different occupational groups “based not on hereditary but on individual qualifications”.

[326][323] Another scholar of religion, Fred Smith, suggests that some of Prabhupada's statements (such as those concerning Hitler) “must be understood in the context of the intellectual and political culture in which he matured”[327] — specifically that of mid-twentieth-century Bengal,[304] brewing with anti-colonialist nationalism championed by such figures as Subhash Chandra Bose, and therefore more favorably disposed to Nazi Germany than to Great Britain.

Criticisms have emerged regarding the movement's organizational structure, controversies have arisen surrounding continuity of leadership after his passing,[342][343] and misdeeds and even criminal acts have been committed by some ISKCON members, including once-respected former leaders.

[8] Representing such thoughts, Harvey Cox, American theologian and Professor of Divinity Emeritus at Harvard University, said: There aren't many people you can think of who successfully implant a whole religious tradition in a completely alien culture.

[375] Various ISKCON-related schools and other institutions have been named after Srila Prabhupada, including the Bhaktivedanta Research Centre in Kolkata, which holds a full collection of the works of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati as well as publications from the first twenty years of the Gaudiya Math.

In one respect, it was the authenticity of Prabhupada’s Krishna faith and practice that enticed new converts to ISKCON and also caused the society to stand out in contrast, and even opposition, to western religious and cultural values.