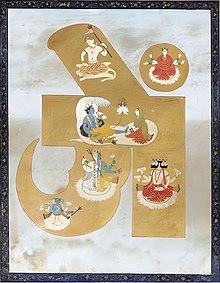

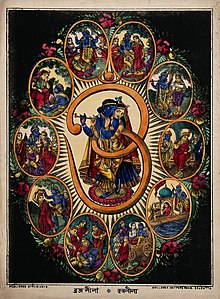

Om

Om (or Aum; listenⓘ; Sanskrit: ॐ, ओम्, romanized: Oṃ, Auṃ, ISO 15919: Ōṁ) is a polysemous symbol representing a sacred sound, syllable, mantra, and invocation in Hinduism.

[7][8][9] In Indian religions, Om serves as a sonic representation of the divine, a standard of Vedic authority and a central aspect of soteriological doctrines and practices.

[13][14] It is part of the iconography found in ancient and medieval era manuscripts, temples, monasteries, and spiritual retreats in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.

[32][33] The Aitareya Brahmana of Rig Veda, in section 5.32, suggests that the three phonetic components of Om (a + u + m) correspond to the three stages of cosmic creation, and when it is read or said, it celebrates the creative powers of the universe.

[9][34] However, in the eight anuvaka of the Taittiriya Upanishad, which consensus research indicates was formulated around the same time or preceding Aitareya Brahmana, the sound Aum is attributed to reflecting the inner part of the word Brahman.

[36] When e and o undergo pluti they typically revert to the original diphthongs with the initial a prolonged,[41] realised as an overlong open back unrounded vowel (ā̄um or a3um [ɑːːum]).

Nagari or Devanagari representations are found epigraphically on sculpture dating from Medieval India and on ancient coins in regional scripts throughout South Asia.

[45][46] Parker (1909) wrote that an "Aum monogram", distinct from the swastika, is found among Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions in Sri Lanka,[47] including Anuradhapura era coins, dated from the 1st to 4th centuries CE, which are embossed with Om along with other symbols.

It frequently appears in sak yant religious tattoos, and has been a part of various flags and official emblems such as in the Thong Chom Klao of King Rama IV (r. 1851–1868)[49] and the present-day royal arms of Cambodia.

[60] Max Muller states that this struggle between gods and demons is considered allegorical by ancient Indian scholars, as good and evil inclinations within man, respectively.

[61][62] Chandogya Upanishad's exposition of syllable Om in its opening chapter combines etymological speculations, symbolism, metric structure and philosophical themes.

[65] The Katha Upanishad is the legendary story of a little boy, Nachiketa, the son of sage Vājaśravasa, who meets Yama, the Vedic deity of death.

[69] The Mundaka Upanishad in the second Mundakam (part), suggests the means to knowing the Atman and the Brahman are meditation, self-reflection, and introspection and that they can be aided by the symbol Om.

Taking as a bow the great weapon of the Upanishad, one should put upon it an arrow sharpened by meditation, Stretching it with a thought directed to the essence of That, Penetrate[K] that Imperishable as the mark, my friend.

This immortality entails an extended celestial existence after a long earthly life, where the practitioner aspires to acquire a divine self (atman) in a non-physical form, allowing them to reside eternally in the heavenly realm.

According to Jeaneane Fowler, verse 9.17 of the Bhagavad Gita synthesizes the competing dualistic and monist streams of thought in Hinduism, by using "Om which is the symbol for the indescribable, impersonal Brahman".

[97] The Bhagavata Purana (9.14.46-48) identifies the Pranava as the root of all Vedic mantras, and describes the combined letters of a-u-m as an invocation of seminal birth, initiation, and the performance of sacrifice (yajña).

The 12th book of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana describes the Goddess as the mother of the Vedas, the Adya Shakti (primal energy, primordial power), and the essence of the Gayatri mantra.

Johnston states this verse highlights the importance of Om in the meditative practice of yoga, where it symbolises the three worlds in the Self; the three times – past, present, and future eternity; the three divine powers – creation, preservation, and transformation in one Being; and three essences in one Spirit – immortality, omniscience, and joy.

The Dravyasamgraha quotes a Prakrit line:[106] ओम एकाक्षर पञ्चपरमेष्ठिनामादिपम् तत्कथमिति चेत अरिहंता असरीरा आयरिया तह उवज्झाया मुणियां Oma ekākṣara pañca-parameṣṭhi-nāmā-dipam tatkathamiti cheta "arihatā asarīrā āyariyā taha uvajjhāyā muṇiyā".

[107] By extension, the Om symbol is also used in Jainism to represent the first five lines of the Namokar mantra,[108] the most important part of the daily prayer in the Jain religion, which honours the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi.

[111] Some scholars interpret the first word of the mantra oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ to be auṃ, with a meaning similar to Hinduism – the totality of sound, existence, and consciousness.

The term is also used in Buddhist architecture and Shinto to describe the paired statues common in Japanese religious settings, most notably the Niō (仁王) and the komainu (狛犬).

[119] Niō statues in Japan, and their equivalent in East Asia, appear in pairs in front of Buddhist temple gates and stupas, in the form of two fierce looking guardian kings (Vajrapani).

[117][118] Komainu, also called lion-dogs, found in Japan, Korea and China, also occur in pairs before Buddhist temples and public spaces, and again, one has an open mouth (Agyō), the other closed (Ungyō).

[121][122][123] Ik Onkar (Punjabi: ਇੱਕ ਓਅੰਕਾਰ; iconically represented as ੴ) are the first words of the Mul Mantar, which is the opening verse of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh scripture.

[128] Ik Onkar is a significant name of God in the Guru Granth Sahib and Gurbani, states Kohli, and occurs as "Aum" in the Upanishads and where it is understood as the abstract representation of three worlds (Trailokya) of creation.

[129][N] According to Wazir Singh, Onkar is a "variation of Om (Aum) of the ancient Indian scriptures (with a change in its orthography), implying the unifying seed-force that evolves as the universe".

[citation needed] For both symbolic and numerological reasons, Aleister Crowley adapted aum into a Thelemic magical formula, AUMGN, adding a silent 'g' (as in the word 'gnosis') and a nasal 'n' to the m to form the compound letter 'MGN'; the 'g' makes explicit the silence previously only implied by the terminal 'm' while the 'n' indicates nasal vocalisation connoting the breath of life and together they connote knowledge and generation.

[131][132][133][134] The Brahmic script Om-ligature has become widely recognized in Western counterculture since the 1960s, mostly in its standard Devanagari form (ॐ), but the Tibetan Om (ༀ) has also gained limited currency in popular culture.