Presidential system

The Pilgrims, permitted to govern themselves in Plymouth Colony, established a system that utilized an independent executive branch.

[4] Drawing inspiration from the previous colonial governments, from English Common Law, and from philosophers such as John Locke and Montesquieu, the delegates developed what is now known as the presidential system.

[4] Following several decades of monarchy, Brazil also adopted the presidential system in 1889 with Deodoro da Fonseca as its first president.

[6][7][8] Following the pattern of other Spanish colonies, the Philippines established the first presidential system in Asia in 1898, but it fell under American control due to the Spanish–American War.

[citation needed] Cyprus,[13] the Maldives,[14] and South Vietnam[15] also adopted the presidential system following decolonization.

A modified version of the presidential system was implemented in Iran following constitutional reform in 1989 in which the Supreme Leader serves as the head of state and is the absolute power in this country.

Opponents of presidential systems cite the potential for gridlock, the difficulty of changing leadership, and concerns that a unitary executive can give way to a dictatorship.

This is in contrast with a parliamentary system, where the majority party in the legislature that also serves as the executive is unlikely to scrutinize its actions.

[citation needed] When an action is within the scope of a president's power, a presidential system can respond more rapidly to emerging situations than parliamentary ones.

A prime minister, when taking action, needs to retain the support of the legislature, but a president is often less constrained.

In Why England Slept, future U.S. president John F. Kennedy argued that British prime ministers Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain were constrained by the need to maintain the confidence of the Commons.

[30] James Wilson, who advocated for a presidential system at the constitutional convention, maintained that a single chief executive would provide for greater public accountability than a group and thereby protect against tyranny by making it plain who was responsible for executive actions.

He also submitted that a singular chief executive was necessary to ensure promptness and consistency and guard against deadlock, which could be essential in times of national emergency.

This gridlock is a common occurrence, as the electorate often expects more rapid results than are possible from new policies and switches to a different party at the next election.

[32] Critics such as Juan Linz, argue that in such cases of gridlock, presidential systems do not offer voters the kind of accountability seen in parliamentary systems and that this inherent political instability can cause democracies to fail, as seen in such cases as Brazil and Allende's Chile.

[34] Years before becoming president, Woodrow Wilson famously wrote "how is the schoolmaster, the nation, to know which boy needs the whipping?

[38] Presidential systems are typically understood as having a head of government elected by citizens to serve one or more fixed terms.

This allows presidents the ability to select cabinet members based as much or more on their ability and competency to lead a particular department as on their loyalty to the president, as opposed to parliamentary cabinets, which might be filled by legislators chosen for no better reason than their perceived loyalty to the prime minister.

Some political scientists dispute this concept of stability, arguing that presidential systems have difficulty sustaining democratic practices and that they have slipped into authoritarianism in many of the countries in which they have been implemented.

According to political scientist Fred Riggs, presidential systems have fallen into authoritarianism in nearly every country they've been attempted.

[39][40] The list of the world's 22 older democracies includes only two countries (Costa Rica and the United States) with presidential systems.

[41] Yale political scientist Juan Linz argues that:[33] The danger that zero-sum presidential elections pose is compounded by the rigidity of the president's fixed term in office.

Even if a president is "proved to be inefficient, even if he becomes unpopular, even if his policy is unacceptable to the majority of his countrymen, he and his methods must be endured until the moment comes for a new election".

[citation needed] Some critics, however, argue that the presidential system is weaker because it does not allow a transfer of power in the event of an emergency.

The following countries have presidential systems where the post of prime minister (official title may vary) exists alongside that of the president.

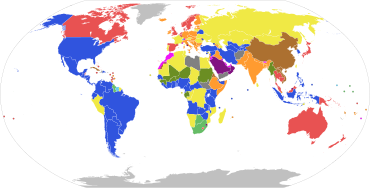

Parliamentary systems : Head of government is elected or nominated by and accountable to the legislature

Presidential system : Head of government (president) is popularly elected and independent of the legislature

Hybrid systems:

Other systems:

Note: this chart represents the de jure systems of government, not the de facto degree of democracy.