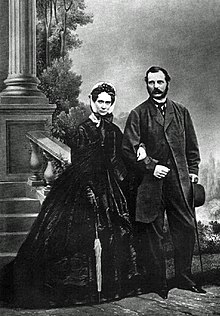

Maria Alexandrovna (Marie of Hesse)

The daughter of Ludwig II, Grand Duke of Hesse, and of Princess Wilhelmine of Baden, she was given a good education and raised in relative austerity, with an emphasis on simplicity, piety and domesticity.

Her mother died when Marie was only twelve, and when she was fourteen, she caught the eye of Tsesarevich Alexander Nikolaevich, who was visiting her father's court while making his Grand tour of Western Europe.

Despite identifying strongly with Russia and Russian interests, she visited her native Hesse regularly every year from the early 1860s onward, and kept in touch with her own family, as also with her husband's relatives across Europe.

Although her parents were double first cousins, they were a mismatched couple:[3] Ludwig was dull, shy and withdrawn, while Wilhelmine, eleven years his junior, was pretty and charming.

In 1828, Princess Wilhelmine moved with her two younger children and their household to Heiligenberg, a mountainside estate nestled on a hill overlooking the village of Jugenheim that she purchased that same year.

After her mother died of tuberculosis,[6] her lady-in-waiting and possible paternal aunt, Marianne von Senarclens de Grancy, successfully took over the responsibility of 11-years-old Marie's education.

In 1839, Tsesarevich Alexander Nikolaevich, son of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, traveled to western Europe to complete his education and search for a wife.

[8][7] Invited to a performance of Gaspare Spontini's La vestale by the Grand Duke, Alexander was introduced to 14-year-old Marie, who was slender and tall for her age, but still wore her hair loose.

[14] Two generations earlier, another princess of Hesse-Darmstadt had married a Tsesarevich: Marie's paternal great-aunt, Natalia Alexeievna, was the first wife of Tsar Paul I.

French plays, operas and new ballets were performed in the Chinese theater, and each Sunday her future mother-in-law gave a banquet in the Alexander Palace.

[4] Years later, her-lady-in waiting Anna Tiutcheva was to write about this period in the life of her mistress: "Having been raised in seclusion even, one might say, in austerity, in the little castle of Jugenheim, where she saw her father only rarely, she was more frightened than bedazzled when she was suddenly brought to the most opulent and brilliant court of all European nations.

He ordered that banquets of fresh strawberries should be placed on his wife's dining table and enjoyed her company spending his mornings sitting on her bed.

Alongside her husband, Maria read Mikhail Lermontov's A Hero of Our Time, Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls, Fyodor Dostoevsky's Poor Folk, and later, Ivan Turgenev's A Sportsman's Sketches, sharing Alexander's sympathies for the plight of the serfs and becoming an ardent abolitionist.

[citation needed] Sixteen months after her wedding, Maria Alexandrovna gave birth to her first child, Alexandra, born in August 1842, two years after her arrival in Russia.

To mark each birth, Alexander and Maria planted oak trees in their private garden at Tsarskoye Selo, where skittles, swings and slides were provided for the children.

Although her facial features were regular, her beauty lay in the delicate color of her skin and her large blue eyes, which looked at you with both perception and timidity... She seemed almost out of place and uneasy in her role as mother, wife, and empress.

Her mind was like her soul: refined, subtle, penetrating and extremely ironic, but lacking in breadth and initiative.On 18 February 1855, Nicholas I died of pneumonia and was succeeded by Alexander to the Russian throne as Tsar.

When four court ladies tried to fix the crown to the 30-years-old Empress's head it nearly clattered to the ground, saved only by the fold of her cloak, a bad omen by the time.

21 September] 1860, she gave birth to Paul, her eighth and final child,[32] but was so weakened that she was forced to spend several months resting on a couch in her boudoir in the Winter Palace.

[32] Since Russian tradition gave precedence to the Empress Mother over the reigning tsar's consort, it was only then that Maria Alexandrovna took a more decisive role in charitable activities.

[35] Maria Alexandrovna was the supreme patroness of the Red Cross: In total, she patronized 5 hospitals, 12 alms-houses, 30 shelters, 2 institutes, 38 gymnasiums, 156 lower schools, and 5 private charitable societies.

[35] Tsar Alexander II relied on Maria Alexandrovna's judgment and serious nature to support his government, opening official documents and discussing states of affairs with her.

[14] Instead of letting the gossips affect her, Empress Maria paid great attention to the upbringing and education of her children, carefully choosing experienced teachers and ensuring their environment was strict.

[48] Feeling better, Maria Alexandrovna financed the Mariinsky Theatre in St Peterburg in 1859–1860, built according to the plans of architect Albert Cavos as an opera and ballet house.

The humid summers in Saint Petersburg began to take a toll on Maria's frail constitution, to the point she was absent from Russia's capital for long periods of time.

Princess Dagmar, who was with the Romanovs during her fiancé's final days, was quickly engaged to his brother, the future Emperor Alexander III, whom she would marry the following year.

The Tsarina spent the following year grieving and found some solace with her family in Hesse, since her brother Karl had recently lost his only daughter Anna.

"[54] Tsar Alexander had three children with Princess Dolgorukova,[51] whom he moved into the Imperial Palace during Maria's final illness out of fear that she might become the target of assassins.

[56] Courtiers spread stories that the dying Empress was forced to hear the noise of Catherine's children moving about overhead, but their rooms were actually far away from each other.

In later years, Nicholas II's eldest daughter, Grand Duchess Olga, claimed that as a small child she saw the ghost of her great-grandmother, according to her nanny Margaretta Eagar.