Prosthaphaeresis

Prosthaphaeresis (from the Greek προσθαφαίρεσις) was an algorithm used in the late 16th century and early 17th century for approximate multiplication and division using formulas from trigonometry.

For the 25 years preceding the invention of the logarithm in 1614, it was the only known generally applicable way of approximating products quickly.

[1][2][3] In ancient times the term was used to mean a reduction to bring the apparent place of a moving point or planet to the mean place (see Equation of the center).

Nicholas Copernicus mentions "prosthaphaeresis" several times in his 1543 work De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, to mean the "great parallax" caused by the displacement of the observer due to the Earth's annual motion.

In 16th-century Europe, celestial navigation of ships on long voyages relied heavily on ephemerides to determine their position and course.

These voluminous charts prepared by astronomers detailed the position of stars and planets at various points in time.

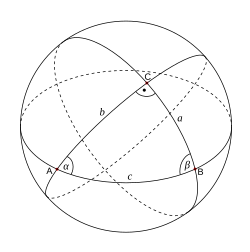

The models used to compute these were based on spherical trigonometry, which relates the angles and arc lengths of spherical triangles (see diagram, right) using formulas such as and where a, b and c are the angles subtended at the centre of the sphere by the corresponding arcs.

Astronomers had to make thousands of such calculations, and because the best method of multiplication available was long multiplication, most of this time was spent taxingly multiplying out products.

Mathematicians, particularly those who were also astronomers, were looking for an easier way, and trigonometry was one of the most advanced and familiar fields to these people.

Prosthaphaeresis appeared in the 1580s, but its originator is not known for certain;[4] its contributors included the mathematicians Ibn Yunis, Johannes Werner, Paul Wittich, Joost Bürgi, Christopher Clavius, and François Viète.

Wittich, Ibn Yunis, and Clavius were all astronomers and have all been credited by various sources with discovering the method.

Its most well-known proponent was Tycho Brahe, who used it extensively for astronomical calculations such as those described above.

It was also used by John Napier, who is credited with inventing the logarithms that would supplant it.

They include the following: The first two of these are believed to have been derived by Jost Bürgi,[citation needed] who related them to [Tycho?]

Using the second formula above, the technique for multiplication of two numbers works as follows: For example, to multiply

: If we want the product of the cosines of the two initial values, which is useful in some of the astronomical calculations mentioned above, this is surprisingly even easier: only steps 3 and 4 above are necessary.

To divide, we exploit the definition of the secant as the reciprocal of the cosine.

, Scaling up to locate the decimal point gives the approximate answer,

Algorithms using the other formulas are similar, but each using different tables (sine, inverse sine, cosine, and inverse cosine) in different places.

In modern terms, prosthaphaeresis can be viewed as relying on the logarithm of complex numbers, in particular on Euler's formula If all the operations are performed with high precision, the product can be as accurate as desired.

Although sums, differences, and averages are easy to compute with high precision, even by hand, trigonometric functions and especially inverse trigonometric functions are not.

Tables were painstakingly constructed for prosthaphaeresis with values for every second, or 3600th of a degree.

Inverse sine and cosine functions are particularly troublesome, because they become steep near −1 and 1.