Protein design

[7] In 2010, one of the most powerful broadly neutralizing antibodies was isolated from patient serum using a computationally designed protein probe.

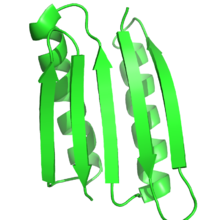

Both de novo designs and protein redesigns can establish rules on the sequence space: the specific amino acids that are allowed at each mutable residue position.

For example, the composition of the surface of the RSC3 probe to select HIV-broadly neutralizing antibodies was restricted based on evolutionary data and charge balancing.

To simplify this space, protein design methods use rotamer libraries that assume ideal values for bond lengths and bond angles, while restricting χ dihedral angles to a few frequently observed low-energy conformations termed rotamers.

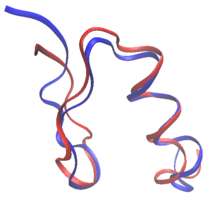

[13][14] Rational protein design techniques must be able to discriminate sequences that will be stable under the target fold from those that would prefer other low-energy competing states.

Thus, protein design requires accurate energy functions that can rank and score sequences by how well they fold to the target structure.

Instead, many protein design algorithms use either physics-based energy functions adapted from molecular mechanics simulation programs, knowledge based energy-functions, or a hybrid mix of both.

[15] Physics-based energy functions, such as AMBER and CHARMM, are typically derived from quantum mechanical simulations, and experimental data from thermodynamics, crystallography, and spectroscopy.

The most common energy functions can be decomposed into pairwise terms between rotamers and amino acid types, which casts the problem as a combinatorial one, and powerful optimization algorithms can be used to solve it.

In those cases, the total energy of each conformation belonging to each sequence can be formulated as a sum of individual and pairwise terms between residue positions.

[14][20][21] Even though the class of problems is NP-hard, in practice many instances of protein design can be solved exactly or optimized satisfactorily through heuristic methods.

Thus, if the predictions of exact algorithms fail when these are experimentally validated, then the source of error can be attributed to the energy function, the allowed flexibility, the sequence space or the target structure (e.g., if it cannot be designed for).

For example, Rosetta Design incorporates sophisticated energy terms, and backbone flexibility using Monte Carlo as the underlying optimizing algorithm.

[25][26] The dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm reduces the search space of the problem iteratively by removing rotamers that can be provably shown to be not part of the global lowest energy conformation (GMEC).

[14][28] A* computes a lower-bound score on each partial tree path that lower bounds (with guarantees) the energy of each of the expanded rotamers.

ILP solvers, such as CPLEX, can compute the exact optimal solution for large instances of protein design problems.

These solvers use a linear programming relaxation of the problem, where qi and qij are allowed to take continuous values, in combination with a branch and cut algorithm to search only a small portion of the conformation space for the optimal solution.

[39] Furthermore, Stephen Mayo and coworkers developed an iterative method to design the most efficient known enzyme for the Kemp-elimination reaction.

[40] Also, in the laboratory of Bruce Donald, computational protein design was used to switch the specificity of one of the protein domains of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase that produces Gramicidin S, from its natural substrate phenylalanine to other noncognate substrates including charged amino acids; the redesigned enzymes had activities close to those of the wild-type.

[41] Semi-rational design is a purposeful modification method based on a certain understanding of the sequence, structure, and catalytic mechanism of enzymes.

The characteristic of semi-rational design is that it does not rely solely on random mutation and screening, but combines the concept of directed evolution.

Semi-rational design has a wide range of applications, including but not limited to enzyme optimization, modification of drug targets, evolution of biocatalysts, etc.

Through this method, researchers can more effectively improve the functional properties of proteins to meet specific biotechnology or medical needs.

Many of the hardest-to-treat diseases, such as Alzheimer's, many forms of cancer (e.g., TP53), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection involve protein–protein interactions.

[43] To overcome this challenge, Bruce Tidor and coworkers developed a method to improve the affinity of antibodies by focusing on electrostatic contributions.

They found that, for the antibodies designed in the study, reducing the desolvation costs of the residues in the interface increased the affinity of the binding pair.

The K* algorithm considers only the lowest-energy conformations of the free and bound complexes (denoted by the sets P, L, and PL) to approximate the partition functions of each complex:[14] The design of protein–protein interactions must be highly specific because proteins can interact with a large number of proteins; successful design requires selective binders.

[48] Recent computational redesign by Costas Maranas and coworkers was also capable of experimentally switching the cofactor specificity of Candida boidinii xylose reductase from NADPH to NADH.

One of the most important applications of protein resurfacing was the design of the RSC3 probe to select broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies at the NIH Vaccine Research Center.

[53] Recently, Costas Maranas and his coworkers developed an automated tool[54] to redesign the pore size of Outer Membrane Porin Type-F (OmpF) from E.coli to any desired sub-nm size and assembled them in membranes to perform precise angstrom scale separation.