Proteomics

[1][2] Proteins are vital macromolecules of all living organisms, with many functions such as the formation of structural fibers of muscle tissue, enzymatic digestion of food, or synthesis and replication of DNA.

In addition, other kinds of proteins include antibodies that protect an organism from infection, and hormones that send important signals throughout the body.

[4] It covers the exploration of proteomes from the overall level of protein composition, structure, and activity, and is an important component of functional genomics.

One major factor affecting reproducibility in proteomics experiments is the simultaneous elution of many more peptides than mass spectrometers can measure.

[22] Notably, targeted proteomics shows increased reproducibility and repeatability compared with shotgun methods, although at the expense of data density and effectiveness.

Proteomic analysis is highly amenable to automation and large data sets are created, which are processed by software algorithms.

Scientists have expressed the need for awareness that proteomics experiments should adhere to the criteria of analytical chemistry (sufficient data quality, sanity check, validation).

[citation needed] Immunoassays can also be carried out using recombinantly generated immunoglobulin derivatives or synthetically designed protein scaffolds that are selected for high antigen specificity.

Such binders include single domain antibody fragments (Nanobodies),[28] designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins)[29] and aptamers.

This capability has the potential to open new advances in diagnostics and therapeutics, but such technologies have been relegated to manual procedures that are not well suited for efficient routine use.

The isolation of phosphorylated peptides has been achieved using isotopic labeling and selective chemistries to capture the fraction of protein among the complex mixture.

When used with LCM, reverse phase arrays can monitor the fluctuating state of proteome among different cell population within a small area of human tissue.

This method can track all kinds of molecular events and can compare diseased and healthy tissues within the same patient enabling the development of treatment strategies and diagnosis.

The ability to acquire proteomics snapshots of neighboring cell populations, using reverse-phase microarrays in conjunction with LCM has a number of applications beyond the study of tumors.

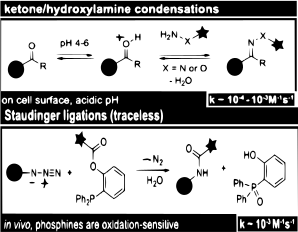

Contrarily slow kinetic reactions like aldehyde and ketone condensation while effective require a high concentration making it cost inefficient.

[49] Proteomics is also used to reveal complex plant-insect interactions that help identify candidate genes involved in the defensive response of plants to herbivory.

[50][51][52] A branch of proteomics called chemoproteomics provides numerous tools and techniques to detect protein targets of drugs.

"[59][60] Understanding the proteome, the structure and function of each protein and the complexities of protein–protein interactions are critical for developing the most effective diagnostic techniques and disease treatments in the future.

Techniques include western blot, immunohistochemical staining, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry and microarray produce peptide fragmentation information but do not give identification of specific proteins present in the original sample.

These programs take the peptide sequences output from mass spectrometry and microarray and return information about matching or similar proteins.

As of 2017, Cryo-electron microscopy is a leading technique, solving difficulties with crystallization (in X-ray crystallography) and conformational ambiguity (in NMR); resolution was 2.2Å as of 2015.

In addition, biomedical engineers are developing methods to factor in the flexibility of protein structures to make comparisons and predictions.

[70] Chemists, biologists and computer scientists are working together to create and introduce new pipelines that allow for analysis of post-translational modifications that have been experimentally identified for their effect on the protein's structure and function.

Computational predictive models[71] have shown that extensive and diverse feto-maternal protein trafficking occurs during pregnancy and can be readily detected non-invasively in maternal whole blood.

Computational models can use fetal gene transcripts previously identified in maternal whole blood to create a comprehensive proteomic network of the term neonate.

Such work shows that the fetal proteins detected in pregnant woman's blood originate from a diverse group of tissues and organs from the developing fetus.

The increasing use of chemical cross-linkers, introduced into living cells to fix protein-protein, protein-DNA and other interactions, may ameliorate this problem partially.

Therefore, describing and quantifying proteome-wide changes in protein abundance is crucial towards understanding biological phenomenon more holistically, on the level of the entire system.

In this way, proteomics can be seen as complementary to genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, metabolomics, and other -omics approaches in integrative analyses attempting to define biological phenotypes more comprehensively.