Protist

[15][16] Protists display a wide range of distinct morphological types that have been used to classify them for practical purposes, although most of these categories do not represent evolutionary cohesive lineages or clades and have instead evolved independently several times.

Molecular techniques such as environmental DNA barcoding have revealed a vast diversity of undescribed protists that accounts for the majority of eukaryotic sequences or operational taxonomic units (OTUs), dwarfing those from plants, animals and fungi.

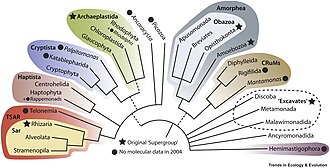

[37] Stramenopiles Alveolata Rhizaria Telonemia Haptista Microhelida Cryptista Archaeplastida1 Discoba Provora Hemimastigophora Meteora sporadica Metamonada Ancyromonadida Malawimonadida CRuMs Amoebozoa Breviatea Apusomonadida Opisthokonta2 The evolutionary relationships of protists have been explained through molecular phylogenetics, the sequencing of entire genomes and transcriptomes, and electron microscopy studies of the flagellar apparatus and cytoskeleton.

[17] Parabasalia (>460 species)[36] is a varied group of anaerobic, mostly endobiotic organisms, ranging from small parasites (like Trichomonas vaginalis, another human pathogen) to giant intestinal symbionts with numerous flagella and nuclei found in wood-eating termites and cockroaches.

[17] Preaxostyla (~140 species) includes the anaerobic and endobiotic oxymonads, with modified (or completely lost)[49][50] mitochondria, and two genera of free-living microaerophilic bacterivorous flagellates Trimastix and Paratrimastix, with typical excavate morphology.

The most basal branching member of the TSAR clade is Telonemia, a small (seven species) phylum of obscure phagotrophic predatory flagellates, found in marine and freshwater environments.

The three most diverse ochrophyte classes are: the diatoms, unicellular or colonial organisms encased in silica cell walls (frustules) that exhibit widely different shapes and ornamentations, responsible for a big portion of the oxygen produced worldwide, and comprising much of the marine phytoplankton;[17][58] the brown algae, filamentous or 'truly' multicellular (with differentiated tissues) macroalgae that constitute the basis of many temperate and cold marine ecosystems, such as kelp forests;[59] and the golden algae, unicellular or colonial flagellates that are mostly present in freshwater habitats.

It includes the labyrinthulomycetes, among which are single-celled amoeboid phagotrophs, mixotrophs, and fungus-like filamentous heterotrophs that create slime networks to move and absorb nutrients, as well as some parasites and a few testate amoebae (Amphitremida).

[63] Free-living ciliates are usually the top heterotrophs and predators in microbial food webs, feeding on bacteria and smaller eukaryotes, present in a variety of ecosystems, although a few species are kleptoplastic.

[67][41]: 600 The other branch of Myzozoa contains the dinoflagellates and their closest relatives, the perkinsids (Perkinsozoa), a small group (26 species) of aquatic intracellular parasites which have lost their photosynthetic ability similarly to apicomplexans.

[69] Rhizaria is a lineage of morphologically diverse organisms, composed almost entirely of unicellular heterotrophic amoebae, flagellates and amoeboflagellates,[17] commonly with reticulose (net-like) or filose (thread-like) pseudopodia for feeding and locomotion.

Cercozoan amoeboflagellates are important predators of other microbes in terrestrial habitats and the plant microbiota (e.g., cercomonads and paracercomonads and glissomonads, collectively known as class Sarcomonadea),[76] and a few can generate slime molds (e.g., Helkesea).

They are mostly marine, comprise an important portion of oceanic plankton, and include the coccolithophores, whose calcified scales ('coccoliths') contribute to the formation of sedimentary rocks and the biogeochemical cycles of carbon and calcium.

[86] The centrohelids (Centroplasthelida) are a small (~95 species)[87] but widespread group of heterotrophic heliozoan-type amoebae, usually covered in scale-bearng mucous, that form an important component of benthic food webs of aquatic habitats, both marine and freshwater.

[111] The Holomycota includes the closest relatives of fungi, the nucleariids, a small group (~50 species) of free-living naked or scale-bearing phagotrophic amoebae with filose pseudopodia, some of which can aggregate into slime moulds.

In ciliates and most phagotrophic flagellates, digestion occurs at the oral region or cytostome, which is covered by a single membrane from which vacuoles are formed; the phagosomes then may be shuttled to the interior of the cell along the cytopharynx.

[136] Osmoregulation is done through active ion transporters of the cell membrane and through contractile vacuoles, specialized organelles that periodically excrete fluid high in potassium and sodium through a cycle of diastole and systole.

[170] Soil-dwelling protist communities are ecologically the richest, possibly be due to the complex and highly dynamic distribution of water in the sediment, which creates extremely heterogenous environmental conditions.

[171] They are the main providers of much of the energy and organic matter used by bacteria, archaea, and higher trophic levels (zooplankton and fish), including essential nutrients such as fatty acids.

Constitutive mixotrophs are present in almost the entire range of oceanic conditions, from eutrophic shallow habitats to oligotrophic subtropical waters but mostly dominating the photic zone, and they account for most of the predation of bacteria.

[177] Traditionally, protists were considered primarily bacterivorous due to biases in cultivation techniques, but many (e.g., vampyrellids, cercomonads, gymnamoebae, testate amoebae, small flagellates) are omnivores that feed on a wide range of soil eukaryotes, including fungi and even some animals such as nematodes.

[138] Necrophagy (the degradation of dead biomass) among microbes is mainly attributed to bacteria and fungi, but protists have a still poorly recognized role as decomposers with specialized lytic enzymes.

In contrast, the algivorous cercozoan family Viridiraptoridae, present in shallow bog waters, are broad-range but sophisticated necrophages that feed on a variety of exclusively dead algae, potentially fulfilling an important role in cleaning up the environment and releasing nutrients for live microbes.

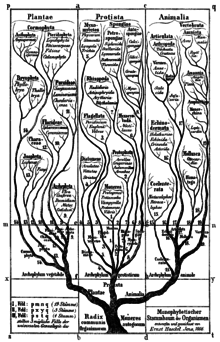

[186][187] In the early 19th century, German naturalist Georg August Goldfuss introduced Protozoa (meaning 'early animals') as a class within Kingdom Animalia,[188] to refer to four very different groups: Infusoria (ciliates), corals, phytozoa (such as Cryptomonas) and jellyfish.

Later, in 1845, Carl Theodor von Siebold was the first to establish Protozoa as a phylum of exclusively unicellular animals consisting of two classes: Infusoria (ciliates) and Rhizopoda (amoebae, foraminifera).

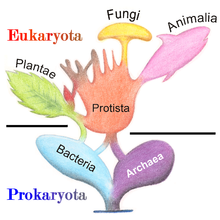

Under his four-kingdom classification (Monera, Protoctista, Plantae, Animalia), the protists and bacteria were finally split apart, recognizing the difference between anucleate (prokaryotic) and nucleate (eukaryotic) organisms.

[197][198][28] In the five-kingdom system of American evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, the term "protist" was reserved for microscopic organisms, while the more inclusive kingdom Protoctista (or protoctists) included certain large multicellular eukaryotes, such as kelp, red algae, and slime molds.

[200] The five-kingdom model remained the accepted classification until the development of molecular phylogenetics in the late 20th century, when it became apparent that protists are a paraphyletic group from which animals, fungi and plants evolved, and the three-domain system (Bacteria, Archaea, Eukarya) became prevalent.

[213] Crown-group eukaryotes achieved significant morphological and ecological diversity before 1000 Ma, with multicellular algae capable of sexual reproduction and unicellular protists exhibiting modern phagocytosis and locomotion.

Their advanced but metabolically expensive sterols likely provided numerous evolutionary advantages due to the increased membrane flexibility, including resilience to osmotic shock during dessication and rehydration cycles, extreme temperatures, UV light exposure, and protection against changing oxygen levels.