Proto-Indo-European language

[1] No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages.

[6] For example, compare the pairs of words in Italian and English: piede and foot, padre and father, pesce and fish.

[7] Detailed analysis suggests a system of sound laws to describe the phonetic and phonological changes from the hypothetical ancestral words to the modern ones.

William Jones, an Anglo-Welsh philologist and puisne judge in Bengal, caused an academic sensation when in 1786 he postulated the common ancestry of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Gothic, the Celtic languages, and Old Persian,[8] but he was not the first to state such a hypothesis.

[10] In a memoir sent to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1767, Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux, a French Jesuit who spent most of his life in India, had specifically demonstrated the analogy between Sanskrit and European languages.

[11] According to current academic consensus, Jones's famous work of 1786 was less accurate than his predecessors', as he erroneously included Egyptian, Japanese and Chinese in the Indo-European languages, while omitting Hindi.

In 1833, he began publishing the Comparative Grammar of Sanskrit, Zend, Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Old Slavic, Gothic, and German.

A subtle new principle won wide acceptance: the laryngeal theory, which explained irregularities in the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European phonology as the effects of hypothetical sounds which no longer exist in all languages documented prior to the excavation of cuneiform tablets in Anatolian.

[18] Julius Pokorny's Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch ('Indo-European Etymological Dictionary', 1959) gave a detailed, though conservative, overview of the lexical knowledge accumulated by 1959.

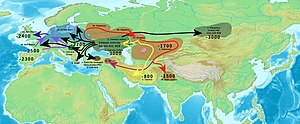

[a] It proposes that the original speakers of PIE were the Yamnaya culture associated with the kurgans (burial mounds) on the Pontic–Caspian steppe north of the Black Sea.

[23]: 305–7 [24] According to the theory, they were nomadic pastoralists who domesticated the horse, which allowed them to migrate across Europe and Asia in wagons and chariots.

[30] Following the publication of several studies on ancient DNA in 2015, Colin Renfrew, the original author and proponent of the Anatolian hypothesis, has accepted the reality of migrations of populations speaking one or several Indo-European languages from the Pontic steppe towards Northwestern Europe.

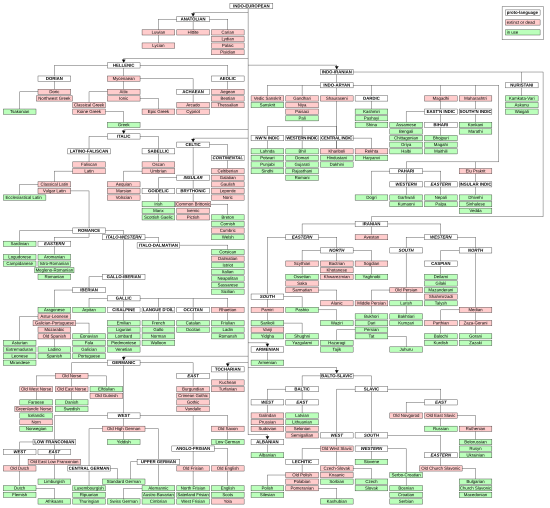

Slavic: Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Sorbian, Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian, Slovenian, Macedonian, Kashubian, Rusyn Iranian: Persian, Pashto, Balochi, Kurdish, Zaza, Ossetian, Luri, Talyshi, Tati, Gilaki, Mazandarani, Semnani, Yaghnobi; Nuristani: Katë, Prasun, Ashkun, Nuristani Kalasha, Tregami, Zemiaki Commonly proposed subgroups of Indo-European languages include Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Aryan, Graeco-Armenian, Graeco-Phrygian, Daco-Thracian, and Thraco-Illyrian.

Albanian and Greek are the only surviving Indo-European descendants of a Paleo-Balkan language area, named for their occurrence in or in the vicinity of the Balkan peninsula.

Forming an exception, Phrygian is sufficiently well-attested to allow proposals of a particularly close affiliation with Greek, and a Graeco-Phrygian branch of Indo-European is becoming increasingly accepted.

The accent is best preserved in Vedic Sanskrit and (in the case of nouns) Ancient Greek, and indirectly attested in a number of phenomena in other IE languages, such as Verner's Law in the Germanic branch.

The subject of a sentence was in the nominative case and agreed in number and person with the verb, which was additionally marked for voice, tense, aspect, and mood.

[45] Proto-Indo-European nominals and verbs were primarily composed of roots – affix-lacking morphemes that carried the core lexical meaning of a word.

[51] Neuter nouns collapsed the nominative, vocative and accusative into a single form, the plural of which used a special collective suffix *-h2 (manifested in most descendants as -a).

The following table shows a possible reconstruction of the PIE verb endings from Sihler, which largely represents the current consensus among Indo-Europeanists.

Reconstructed particles include for example, *upo "under, below"; the negators *ne, *mē; the conjunctions *kʷe "and", *wē "or" and others; and an interjection, *wai!, expressing woe or agony.

If the first element was a noun, this created an adjective that resembled a present participle in meaning, e.g. "having much rice" or "cutting trees".

The syntax of the older Indo-European languages has been studied in earnest since at least the late nineteenth century, by such scholars as Hermann Hirt and Berthold Delbrück.

[58] Since all the early attested IE languages were inflectional, PIE is thought to have relied primarily on morphological markers, rather than word order, to signal syntactic relationships within sentences.

In 1892, Jacob Wackernagel reconstructed PIE's word order as subject–verb–object (SVO), based on evidence in Vedic Sanskrit.

He posits that the presence of person marking in PIE verbs motivated a shift from OV to VO order in later dialects.