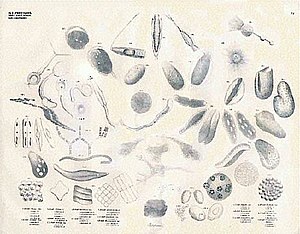

Protozoa

When first introduced by Georg Goldfuss, in 1818, the taxon Protozoa was erected as a class within the Animalia,[3] with the word 'protozoa' meaning "first animals", because they often possess animal-like behaviours, such as motility and predation, and lack a cell wall, as found in plants and many algae.

The taxon 'Protozoa' fails to meet these standards, so grouping protozoa with animals, and treating them as closely related, became no longer justifiable.

The term continues to be used in a loose way to describe single-celled protists (that is, eukaryotes that are not animals, plants, or fungi) that feed by heterotrophy.

[10] The word "protozoa" (singular protozoon) was coined in 1818 by zoologist Georg August Goldfuss (=Goldfuß), as the Greek equivalent of the German Urthiere, meaning "primitive, or original animals" (ur- 'proto-' + Thier 'animal').

[3] Originally, the group included not only single-celled microorganisms but also some "lower" multicellular animals, such as rotifers, corals, sponges, jellyfish, bryozoans and polychaete worms.

The definition of Protozoa as a phylum or sub-kingdom composed of "unicellular animals" was adopted by the zoologist Otto Bütschli—celebrated at his centenary as the "architect of protozoology".

[16] As a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in a simplistic "two-kingdom" concept of life, according to which all living beings were classified as either animals or plants.

In 1860, John Hogg argued against the use of "protozoa", on the grounds that "naturalists are divided in opinion—and probably some will ever continue so—whether many of these organisms or living beings, are animals or plants.

"[18] As an alternative, he proposed a new kingdom called Primigenum, consisting of both the protozoa and unicellular algae, which he combined under the name "Protoctista".

[21] Despite these proposals, Protozoa emerged as the preferred taxonomic placement for heterotrophic microorganisms such as amoebae and ciliates, and remained so for more than a century.

By mid-century, some biologists, such as Herbert Copeland, Robert H. Whittaker and Lynn Margulis, advocated the revival of Haeckel's Protista or Hogg's Protoctista as a kingdom-level eukaryotic group, alongside Plants, Animals and Fungi.

[22][23][24] By 1954, Protozoa were classified as "unicellular animals", as distinct from the "Protophyta", single-celled photosynthetic algae, which were considered primitive plants.

[26] Despite awareness that the traditional Protozoa was not a clade, a natural group with a common ancestor, some authors have continued to use the name, while applying it to differing scopes of organisms.

[27][28][29] A scheme presented by Ruggiero et al. in 2015, placed eight not closely related phyla within Kingdom Protozoa: Euglenozoa, Amoebozoa, Metamonada, Choanozoa sensu Cavalier-Smith, Loukozoa, Percolozoa, Microsporidia and Sulcozoa.

[33] In the system of eukaryote classification published by the International Society of Protistologists in 2012, members of the old phylum Protozoa have been distributed among a variety of supergroups.

[38] However, sexual reproduction is rare among free-living protozoa and it usually occurs when food is scarce or the environment changes drastically.

[43] Free-living protozoa are common and often abundant in fresh, brackish and salt water, as well as other moist environments, such as soils and mosses.

[55] All protozoa require a moist habitat; however, some can survive for long periods of time in dry environments, by forming resting cysts that enable them to remain dormant until conditions improve.

Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic algae (zoochlorellae), which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and provide nutrients to the host.

Some protozoans practice kleptoplasty, stealing chloroplasts from prey organisms and maintaining them within their own cell bodies as they continue to produce nutrients through photosynthesis.

[59] Organisms traditionally classified as protozoa are abundant in aqueous environments and soil, occupying a range of trophic levels.

The bodies of some protozoa are supported internally by rigid, often inorganic, elements (as in Acantharea, Pylocystinea, Phaeodarea – collectively the 'Radiolaria', and Ebriida).

Some of these protozoa have two-phase life cycles, alternating between proliferative stages (e.g., trophozoites) and resting cysts, enabling them to survive harsh conditions.