Pseudogene

This is not surprising, since various biological processes are expected to accidentally create pseudogenes, and there are no specialized mechanisms to remove them from genomes.

Pseudogene sequences may be transcribed into RNA at low levels, due to promoter elements inherited from the ancestral gene or arising by new mutations.

[1] Pseudogenes are sometimes difficult to identify and characterize in genomes, because the two requirements of similarity and loss of functionality are usually implied through sequence alignments rather than biologically proven.

For example, amplification of a gene by PCR may simultaneously amplify a pseudogene that shares similar sequences.

It has been proposed that the identification of processed pseudogenes can help improve the accuracy of gene prediction methods.

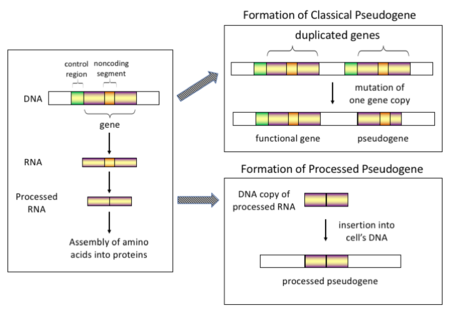

The classifications of pseudogenes are as follows: In higher eukaryotes, particularly mammals, retrotransposition is a fairly common event that has had a huge impact on the composition of the genome.

[9] Once these pseudogenes are inserted back into the genome, they usually contain a poly-A tail, and usually have had their introns spliced out; these are both hallmark features of cDNAs.

Duplicated pseudogenes usually have all the same characteristics as genes, including an intact exon-intron structure and regulatory sequences.

The classic example of a unitary pseudogene is the gene that presumably coded the enzyme L-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase (GULO) in primates.

[26] Lopes-Marques et al. define polymorphic pseudogenes as genes that carry a LoF allele with a frequency higher than 1% (in global or certain sub-populations) and without overt pathogenic consequences when homozygous.

In the human genome, a number of examples have been identified that were originally classified as pseudogenes but later discovered to have a functional, although not necessarily protein-coding, role.

[28][29] Examples include the following: The rapid proliferation of DNA sequencing technologies has led to the identification of many apparent pseudogenes using gene prediction techniques.

Pseudogenes are often identified by the appearance of a premature stop codon in a predicted mRNA sequence, which would, in theory, prevent synthesis (translation) of the normal protein product of the original gene.

As alluded to in the figure above, a small amount of the protein product of such readthrough may still be recognizable and function at some level.

In 2016 it was reported that four predicted pseudogenes in multiple Drosophila species actually encode proteins with biologically important functions,[30] "suggesting that such 'pseudo-pseudogenes' could represent a widespread phenomenon".

[35] An earlier analysis found that human PGAM4 (phosphoglycerate mutase),[36] previously thought to be a pseudogene, is not only functional, but also causes infertility if mutated.

[37][38] A number of pseudo-pseudogenes were also found in prokaryotes, where some stop codon substitutions in essential genes appear to be retained, even positively selected for.

Processing of RNAs transcribed from psiPPM1K yield siRNAs that can act to suppress the most common type of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma.

[42] This and much other research has led to considerable excitement about the possibility of targeting pseudogenes with/as therapeutic agents[43] piRNAs.

However, PTENP1 has a missense mutation which eliminates the codon for the initiating methionine and thus prevents translation of the normal PTEN protein.

[51] Since most bacteria that carry pseudogenes are either symbionts or obligate intracellular parasites, genome size eventually reduces.

[52] Although genome reduction focuses on what genes are not needed by getting rid of pseudogenes, selective pressures from the host can sway what is kept.

In the case of a symbiont from the Verrucomicrobiota phylum, there are seven additional copies of the gene coding the mandelalide pathway.