Pteranodon

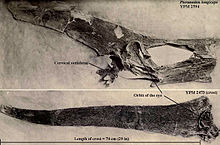

Pteranodon (/təˈrænədɒn/; from Ancient Greek: πτερόν, romanized: pteron 'wing' and ἀνόδων, anodon 'toothless')[2][better source needed] is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with P. longiceps having a wingspan of over 6 m (20 ft).

They lived during the late Cretaceous geological period of North America in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota and Alabama.

In 1876, Othniel Charles Marsh recognised it as a genus of its own, making particular note of its complete lack of teeth, which at the time was unique among pterosaurs.

Its fossils first were found by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1871,[4] in the Late Cretaceous Smoky Hill Chalk deposits of western Kansas.

These chalk beds were deposited at the bottom of what was once the Western Interior Seaway, a large shallow sea over what now is the midsection of the North American continent.

[6] Re-evaluation by later scientists has supported Marsh's case, refuting Cope's assertion that P. umbrosus represented a larger, distinct species.

Marsh recognized this major difference, describing the specimens as "distinguished from all previously known genera of the order Pterosauria by the entire absence of teeth."

He noticed that, in 1871, Seeley had mentioned the existence of a partial set of toothless pterosaur jaws from the Cambridge Greensand of England, which he named Ornithostoma.

[5] However, both Williston and Pleininger were incorrect, because unnoticed by both of them was the fact that, in 1891, Seeley himself had finally described and properly named Ornithostoma, assigning it to the species O. sedgwicki.

In the 2010s, more research on the identity of Ornithostoma showed that it was probably not Pteranodon or even a close relative, but may in fact have been an azhdarchoid, a different type of toothless pterosaur.

He considered both P. comptus and P. nanus to be specimens of Nyctosaurus, and divided the others into small (P. velox), medium (P. occidentalis), and large species (P. ingens), based primarily on the shape of their upper arm bones.

[11] However, Miller made several mistakes in his study concerning which specimens Marsh had assigned to which species, and most scientists disregarded his work on the subject in their later research.

[5] In 1984, Robert Milton Schoch published another revision that essentially returned to Marsh's original classification scheme, most notably sinking P. longiceps as a synonym of P.

[14] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, S. Christopher Bennett published several major papers reviewing the anatomy, taxonomy and life history of Pteranodon.

The upstroke of the wings would have occurred when the animal cleared the ground followed by a rapid down-stroke to generate additional lift and complete the launch into the air.

[33] The earliest model of Pteranodon locomotion, put forward by Cherrie D. Bramwell and G. R. Whitfield, suggested that they were utterly incapable of walking or standing.

[36][37] In 2004, Sankar Chatterjee and R. J. Templin proposed a dual system, wherein pterosaurs walked quadrupedally most of the time, but opted for a bipedal takeoff.

Scientific interpretations of the crest's function began in 1910, when George Francis Eaton proposed two possibilities: an aerodynamic counterbalance and a muscle attachment point.

[17] Eaton had suggested that a secondary function of the crest might have been as a counterbalance against the long beak, reducing the need for heavy neck muscles to control the orientation of the head.

The suggestion that the crest was an air brake, and that the animals would turn their heads to the side in order to slow down, suffers from a similar problem.

This strongly suggests that the natural geographic range of Pteranodon covered only the southern part of the Niobrara, and that its habitat did not extend farther north than South Dakota.

[5] Some remains from Japan have also been tentatively attributed to Pteranodon, but their distance from its known Western Interior Seaway habitat makes this identification unlikely.

Vertebrate life, apart from basal fish, included sea turtles, such as Toxochelys, the plesiosaurs Elasmosaurus and Styxosaurus, and the flightless diving bird Parahesperornis.

[45] Fossils from terrestrial dinosaurs also have been found in the Niobrara Chalk, suggesting that animals who died on shore must have been washed out to sea (one specimen of a hadrosaur appears to have been scavenged by a shark).

A possible third species, which Kellner named Geosternbergia maiseyi in 2010, is known from the Sharon Springs member of the Pierre Shale Formation in Kansas, Wyoming, and South Dakota, dating to between 81.5 and 80.5 million years ago.

However, aside from the differences between males and females described above, the post-cranial skeletons of Pteranodon show little to no variation between species or specimens, and the bodies and wings of all pteranodonts were essentially identical.

[48] Muzquizopteryx coahuilensis "Nyctosaurus" lamegoi Nyctosaurus gracilis Alamodactylus byrdi Pteranodon longiceps Pteranodon sternbergi Longchengpterus zhaoi Nurhachius ignaciobritoi Liaoxipterus brachyognathus Istiodactylus latidens Istiodactylus sinensis Lonchodectes compressirostris Aetodactylus halli Cearadactylus atrox Brasileodactylus araripensis Ludodactylus sibbicki Ornithocheirae Due to the subtle variations between specimens of pteranodontid from the Niobrara Formation, most researchers have assigned all of them to the single genus Pteranodon, in at least two species (P. longiceps and P. sternbergi) distinguished mainly by the shape of the crest.

Most prominent pterosaur researchers of the late 20th century however, including S. Christopher Bennett and Peter Wellnhofer, did not adopt these subgeneric names, and continued to place all pteranodont species into the single genus Pteranodon.

He placed P. sternbergi into the genus named by Miller, Geosternbergia, along with the Pierre Shale skull specimen which Bennett had previously considered to be a large male P. longiceps.

Numerous other pteranodont specimens are known from the same formation and time period, and Kellner suggested they may belong to the same species as G. maiseyi, but because they lack skulls, he could not confidently identify them.