Ptolemy

The Catholic Church promoted his work, which included the only mathematically sound geocentric model of the Solar System, and unlike most Greek mathematicians, Ptolemy's writings (foremost the Almagest) never ceased to be copied or commented upon, both in late antiquity and in the Middle Ages.

[3] However, it is likely that only a few truly mastered the mathematics necessary to understand his works, as evidenced particularly by the many abridged and watered-down introductions to Ptolemy's astronomy that were popular among the Arabs and Byzantines.

The 14th-century astronomer Theodore Meliteniotes wrote that Ptolemy's birthplace was Ptolemais Hermiou, a Greek city in the Thebaid region of Egypt (now El Mansha, Sohag Governorate).

Abu Ma'shar recorded a belief that a different member of this royal line "composed the book on astrology and attributed it to Ptolemy".

"[18] Not much positive evidence is known on the subject of Ptolemy's ancestry, apart from what can be drawn from the details of his name, although modern scholars have concluded that Abu Ma'shar's account is erroneous.

[31] The earliest person who attempted to merge these two approaches was Hipparchus, who produced geometric models that not only reflected the arrangement of the planets and stars but could be used to calculate celestial motions.

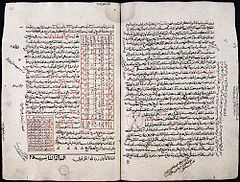

[32] Ptolemy presented his astronomical models alongside convenient tables, which could be used to compute the future or past position of the planets.

Under the scrutiny of modern scholarship, and the cross-checking of observations contained in the Almagest against figures produced through backwards extrapolation, various patterns of errors have emerged within the work.

[38][39] A prominent miscalculation is Ptolemy's use of measurements that he claimed were taken at noon, but which systematically produce readings now shown to be off by half an hour, as if the observations were taken at 12:30pm.

[39] The charges laid by Newton and others have been the subject of wide discussions and received significant push back from other scholars against the findings.

[38] Owen Gingerich, while agreeing that the Almagest contains "some remarkably fishy numbers",[38] including in the matter of the 30-hour displaced equinox, which he noted aligned perfectly with predictions made by Hipparchus 278 years earlier,[41] rejected the qualification of fraud.

[38] Objections were also raised by Bernard Goldstein, who questioned Newton's findings and suggested that he had misunderstood the secondary literature, while noting that issues with the accuracy of Ptolemy's observations had long been known.

[42][43] In 2022 the first Greek fragments of Hipparchus' lost star catalog were discovered in a palimpsest and they debunked accusations made by the French astronomer Delambre in the early 1800s which were repeated by R.R.

'Hypotheses of the Planets') is a cosmological work, probably one of the last written by Ptolemy, in two books dealing with the structure of the universe and the laws that govern celestial motion.

[49] The work is also notable for having descriptions on how to build instruments to depict the planets and their movements from a geocentric perspective, much as an orrery would have done for a heliocentric one, presumably for didactic purposes.

It begins: "To the saviour god, Claudius Ptolemy (dedicates) the first principles and models of astronomy", following by a catalogue of numbers that define a system of celestial mechanics governing the motions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars.

[58][59] He relied on previous work by an earlier geographer, Marinus of Tyre, as well as on gazetteers of the Roman and ancient Persian Empire.

Ptolemy's real innovation, however, occurs in the second part of the book, where he provides a catalogue of 8,000 localities he collected from Marinus and others, the biggest such database from antiquity.

[62] One of the places Ptolemy noted specific coordinates for was the now-lost stone tower which marked the midpoint on the ancient Silk Road, and which scholars have been trying to locate ever since.

His oikoumenē spanned 180 degrees of longitude from the Blessed Islands in the Atlantic Ocean to the middle of China, and about 80 degrees of latitude from Shetland to anti-Meroe (east coast of Africa); Ptolemy was well aware that he knew about only a quarter of the globe, and an erroneous extension of China southward suggests his sources did not reach all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

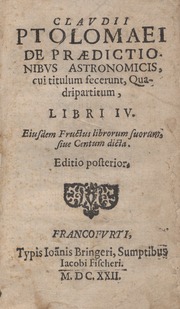

[65] Its original title is unknown, but may have been a term found in some Greek manuscripts, Apotelesmatiká (biblía), roughly meaning "(books) on the Effects" or "Outcomes", or "Prognostics".

[66] Much of the content of the Tetrabiblos was collected from earlier sources; Ptolemy's achievement was to order his material in a systematic way, showing how the subject could, in his view, be rationalized.

[68] A collection of one hundred aphorisms about astrology called the Centiloquium, ascribed to Ptolemy, was widely reproduced and commented on by Arabic, Latin, and Hebrew scholars, and often bound together in medieval manuscripts after the Tetrabiblos as a kind of summation.

[73][74] Ptolemy reviewed standard (and ancient, disused) musical tuning practice of his day, which he then compared to his own subdivisions of the tetrachord and the octave, which he derived experimentally using a monochord / harmonic canon.

In particular, it is a nascent form of what in the following millennium developed into the scientific method, with specific descriptions of the experimental apparatus that he built and used to test musical conjectures, and the empirical musical relations he identified by testing pitches against each other: He was able to accurately measure relative pitches based on the ratios of vibrating lengths two separate sides of the same single string, hence which were assured to be under equal tension, eliminating one source of error.

He analyzed the empirically determined ratios of "pleasant" pairs of pitches, and then synthesised all of them into a coherent mathematical description, which persists to the present as just intonation – the standard for comparison of consonance in the many other, less-than exact but more facile compromise tuning systems.

[76][77] During the Renaissance, Ptolemy's ideas inspired Kepler in his own musings on the harmony of the world (Harmonice Mundi, Appendix to Book V).

He offered an obscure explanation of the Sun or Moon illusion (the enlarged apparent size on the horizon) based on the difficulty of looking upwards.

[79][85] This was one of the early statements of size-distance invariance as a cause of perceptual size and shape constancy, a view supported by the Stoics.

[87] He wrote a short essay entitled On the Criterion and Hegemonikon (Greek: Περὶ Κριτηρίου καὶ Ἡγεμονικοῡ), which may have been one of his earliest works.