Punic religion

[2] An important sacred space in Punic religion appears to have been the large open air sanctuaries known as tophets in modern scholarship, in which urns containing the cremated bones of infants and animals were buried.

At Leptis Magna, a number of unique gods are attested, many of them in Punic-Latin bilingual inscriptions, such as El-qone-eres, Milkashtart (Hercules), and Shadrafa (Liber Pater).

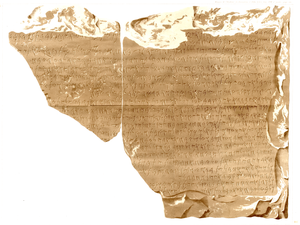

Shared formulas and phrasing show it belongs to a Near Eastern treaty tradition, with parallels attested in Hittite, Akkadian, and Aramaic.

[22][8] There is very little evidence for a Punic mythology, but some scholars have seen an original Carthaginian myth behind the story of the foundation of Carthage that is reported by Greek and Latin sources, especially Josephus and Vergil.

In this story, Elissa (or Dido) flees Tyre after her brother, king Pygmalion murders her husband, a priest of Melqart, and establishes the city of Carthage.

[34] A short papyrus found in a tomb at Tal-Virtù in Malta suggests a belief that the dead had to cross a body of water to enter the afterlife.

[35] Tombs could take the form of fossae (rectangular graves cut into the earth or bedrock), pozzi (shallow, round pits), and hypogea (rock-cut chambers with stone benches on which the deceased was laid).

At Hoya de los Rastros, near Ayamonte in Spain, for example, the bones were arranged in order in their urns so that the feet were at the bottom and the skull at the top.

[44][38] Examples are known from Tharros and Sulci in Sardinia,[45] Lilybaeum in Sicily, Casa del Obispo at Gades in Spain,[46] and Carthage and Kerkouane in Tunisia.

[40] Before burial, the deceased was anointed with perfumed resin,[47] coloured red with ochre or cinnabar,[48] traces of which have been recovered archaeologically.

[50] The feasts included the consumption of wine,[50] which may have had symbolic links to blood, the fertility of the Earth, and new life, as it did for other Mediterranean peoples.

[50] These funerary feasts were repeated at regular intervals as part of a cult of the ancestors (called rpʼm, cognate with the Hebrew rephaim).

[59] Grave offerings could include carved masks[21] and amulets, especially the eye of Horus (wadjet) and small glass apotropaic heads (protomae), which were intended to protect the deceased.

[20][33] They were often accompanied by a standardised set of feasting equipment for the deceased, consisting of two jugs, a drinking bowl, and an oil lamp.

[49][64] Bronze cymbals and bells found in some tombs may derive from songs and music played at the funeral of the deceased - perhaps intended to ward off evil spirits.

[65][66] Most Punic grave stelae, in addition to an engraved text and sometimes a standing figure bearing a libation cup, show a standard repertoire of (religious) symbols.

It is thought that such symbols, which may be compared to a cross on a Christian gravestone, generally represent "deities or beliefs related to the after-life, aimed probably at facilitating or at protecting the eternal rest of the deceased".

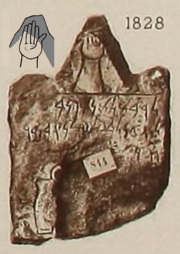

[68] The main Punic funerary symbols are:[68][69] Animals and other valuables were sacrificed to propitiate the gods; such sacrifices had to be done according to strict specifications,[20] which are described on nine surviving inscriptions known as "sacrificial tariffs.

[72] Many of these tophet inscriptions refer to the sacrificial ritual as mlk (vocalized mulk or molk), which some scholars connect with the biblical Moloch.

[75] A fifth-century BC inscription (KAI 72) from Ebusus records the dedication of a temple, first to Rašap-Melqart, and then to Tinnit and Gad by a priest who states that the process involved making a vow.

[78] A custom attested at Byblos by the Greek author Lucian of Samosata that those sacrificing to Melqart had to shave their heads may explain ritual razors found in many Carthaginian tombs.

[12] Classical writers describing some version of child sacrifice to "Cronos" (Baal Hammon) include the Greek historians Diodorus Siculus and Cleitarchus, as well as the Christian apologists Tertullian and Orosius.

[79][80] These descriptions were compared to those found in the Hebrew Bible describing the sacrifice of children by burning to Baal and Moloch at a place called Tophet.

[79] The ancient descriptions were seemingly confirmed by the discovering of the so-called "Tophet of Salammbô" in Carthage in 1921, which contained the urns of cremated children.

[84] The specific sort of open aired sanctuary described as a Tophet in modern scholarship is unique to the Punic communities of the Western Mediterranean.

[93] In addition to infants, some of these tophets contain offerings only of goats, sheep, birds, or plants; many of the worshipers have Libyan rather than Punic names.

[81] Child sacrifice may have been overemphasized for effect; after the Romans finally defeated Carthage and totally destroyed the city, they engaged in postwar propaganda to make their archenemies seem cruel and less civilized.

[99] In Xella's estimation, prenatal remains at the tophet are probably those of children who were promised to be sacrificed but died before birth, but who were nevertheless offered as a sacrifice in fulfillment of a vow.