Pyramid of Sahure

The site was first thoroughly excavated by Ludwig Borchardt between March 1907 and 1908, who wrote the standard work Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahu-Re (English: The Funerary Monument of King Sahure) between 1910 and 1913.

Compared to the preceding Fourth Dynasty, the immensity of the constructions was dramatically reduced but, in tandem, the decorative programme proliferated and temples were augmented by enlarged storeroom complexes.

This period heralded the first wave of destruction on the Abusir monuments, whilst Sahure's escaped the dismantlement, possibly as a result of the cult's presence.

At the beginning of the Christian era, Sahure's temple became the site of a Coptic shrine, as evidenced by the recovery of pottery and graffiti dating to between the 4th and 7th century AD.

[30] Five years later, Karl Richard Lepsius, sponsored by King Frederick William IV of Prussia,[33][34] explored the Abusir necropolis and catalogued Sahure's pyramid as XVIII.

[37] The archeologist Zahi Hawass had a segment of Sahure's causeway cleaned and reconstructed, during which large relief-decorated limestone blocks that had been buried in the sand were uncovered.

[51] The complex is well-decorated, containing thematically diverse relief-work identified by the Egyptologist Miroslav Verner as "the highest level of the genre" found in the Old Kingdom.

Although the subsoil of the area has never been investigated, evidence from the nearby mastaba of Ptahshepses suggests that the pyramid was not embedded into bedrock, but on a platform constructed from at least two layers of limestone.

[57] A ditch was left in the pyramid's north face during construction, which allowed workers to build the inner corridor and chambers while the core was being erected around it, before filling it in with rubble.

[43][75] The chambers had a ceiling constructed from three gabled layers of limestone blocks,[24][43] which dispersed the weight from the superstructure onto either side of the passageway preventing collapse.

[71] Inside the apartment's ruins, Perring found stone fragments – the only discovered remains of the burial[24] – which he believed belonged to the king's basalt sarcophagus.

[84] The room was originally adorned with polychromatic relief,[44] and contained a scene depicting the king, as a sphinx or griffin, trampling captive Near Eastern and Libyan enemies led to him by the gods.

[24] The causeway was roofed, with narrow slits left in the ceiling slabs allowing light to enter, illuminating its walls covered in polychromatic bas-relief.

[38] The scene was thought only to exist in Unas' causeway, and was thus believed to be unique eyewitness testimony to the declining living standards of Saharan nomads brought about by the end of the Sahara wet phase in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC.

[90] Instead, Miroslav Verner suggests that the nomads might have been brought into the pyramid town to demonstrate the hardships faced by builders bringing higher-quality stone from remote mountain areas.

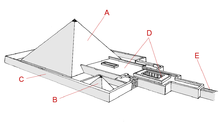

[112] The mortuary temple was an expansive, rectangular building positioned along the east–west axis,[45] and situated on a level surface built from two layers of limestone blocks in front of the main pyramid's east face.

[117] Contemporary sources identify this room as the pr-wrw meaning "House of the Great Ones",[43][117] and it may be a replica of the hall of the royal palace, where nobles were received and certain rituals performed.

[124] The Egyptologist Mark Lehner suggests that the corridor represented the untamed wilderness, surrounding a clearing – the open courtyard – of which the king was guarantor.

[43][129] Each was 6.4 m (21 ft) tall,[129] and carved into the form of date palms, symbolising fertility and immortality, upon which the king's name and titulary was inscribed[43] and painted in green.

[135] On the north half of the corridor's east wall is a relief, considered by the Egyptologist Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards to be amongst the most interesting in the temple, that depicts the king and his court observing the departure of twelve sea-going vessels, probably on expedition to Syria or Palestine.

[121] In the south-half, a similar scene depicts the king and his court awaiting the arrival of ships laden with cargo and several Near Eastern peoples, who do not appear to be prisoners, indicating either a commercial or, perhaps, diplomatic mission.

[135] The niche's walls were decorated with reliefs depicting processions of offering bearers, and they had recessed side doors leading to two-story storage galleries.

[76][136] The northern gallery consisted of ten rooms arranged in two rows, each outfitted with its own staircase – cut directly into the limestone walls[50] – leading to the second story.

[138] A low alabaster altar stood at the west wall,[136] at the foot of a granite false door, possibly covered in copper or gold, through which the spirit of the king would enter the room to receive his meal, before returning to his tomb.

[143] The room also originally contained a black granite statue and an offering basin, located in a recessed niche in its south-west corner, with an outflow of copper piping.

[50][76][144] These were connected via an intricate network of copper pipes laid beneath the temple, which led down the length of the causeway before terminating at an outlet on its southern side.

The reliefs portrayed rows of deities, nome and estate personifications, and fertility figures – all clutching was-sceptres and ankh signs – marching into the temple.

[7] From the north face,[151] a bent corridor – initially descending, then switching to an ascent – leads into the miniature pyramid's sole chamber: an east–west oriented burial room slightly below ground level.

[50] The funerary cults at Abusir remained active through the reign of Pepi II at the end of the Sixth Dynasty,[155] but their continuation beyond this time is a matter of dispute.

[182] A third wave of dismantlement of the Abusir monuments is attested in the Roman period by the abundant remains of mill-stones, lime production facilities, and worker shelters.