Pythagoreanism

Already during Pythagoras' life it is likely that the distinction between the akousmatikoi ("those who listen"), who is conventionally regarded as more concerned with religious, and ritual elements, and associated with the oral tradition, and the mathematikoi ("those who learn") existed.

Yet according to Plutarch it was the Athenian strategos (general) Kimon Milkiadou (c. 510 – c. 450 BC) who converted this, "waterless and arid spot into a well watered grove, which he provided with clear running-tracks and shady walks".

The worship of Pythagoras continued in Italy and as a religious community Pythagoreans appear to have survived as part of, or deeply influenced, the Bacchic cults and Orphism.

[4] Much of the surviving sources on Pythagoras originated with Aristotle and the philosophers of the Peripatetic school, which founded historiographical academic traditions such as biography, doxography and the history of science.

The akousmatikoi philosophers refused to recognise that the continuous development of mathematical and scientific research conducted by the mathēmatikoi was in line with Pythagoras's intention.

Until the demise of Pythagoreanism in the 4th century BC, the akousmatikoi continued to engage in a pious life by practicing silence, dressing simply and avoiding meat, for the purpose of attaining a privileged afterlife.

[30] The 4th century Greek historian and sceptic philosopher Hecataeus of Abdera asserted that Pythagoras had been inspired by ancient Egyptian philosophy in his use of ritual regulations and his belief in reincarnation.

[36] The Pythagoreans engaged with geometry as a liberal philosophy which served to establish principles and allowed theorems to be explored abstractly and rationally.

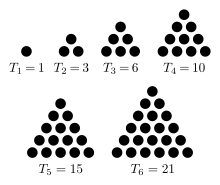

[37] Pythagoras is credited with discovering that the most harmonious musical intervals are created by the simple numerical ratio of the first four natural numbers which derive respectively from the relations of string length: the octave (1/2), the fifth (2/3) and the fourth (3/4).

Pythagoreans used different types of music to arouse or calm their souls,[41] and certain stirring songs could have notes that existed in the same ratio as the "distances of the heavenly bodies from the centre of" Earth.

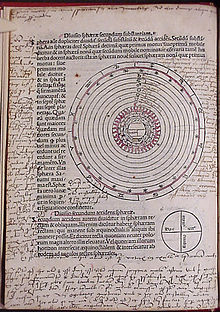

[45] According to Aristotle's student Eudemus of Cyprus, the first philosopher to determine quantitatively the size of the known planets and the distance between them was Anaximander, a teacher to Pythagoras, in the 6th century BC.

Instead, as Aristotle noted, the Pythagorean view of the astronomical system was grounded in a fundamental reflection on the value of individual things and the hierarchical order of the universe.

[46] The early-Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus argued that the structure of the cosmos was determined by the musical numerical proportions of the diatonic octave, which contained the fifth and fourth harmonic intervals.

[50] A surviving fragment from the 3rd century BC by the late-Pythagorean philosopher Aesara reasoned that: I think human nature provides a common standard of law and justice for both the family and the city.

Thus Porphyry would rely on the teachings of the Pythagoreans when arguing that abstinence from eating meat for the purpose of spiritual purification should be practiced only by philosophers, whose aim was to reach a divine state.

Her assertion that a wife should remain devoted to her husband, regardless of his behavior, has been interpreted by scholars as a pragmatic response to the legal rights of women in Athens.

[64] Pythagoras' teachings and Pythagoreanism influenced Plato's writings on physical cosmology, psychology, ethics and political philosophy in the 5th century BC.

However, Plato's views that the primary role of mathematics was to turn the soul towards the world of forms, as expressed in Timaeus, is regarded as Platonic philosophy, rather than Pythagorean.

[72] In the Middle Ages this numerological division of the universe was credited to the Pythagoreans, while early on it was regarded as an authoritative source of Christian doctrine by Photius and John of Sacrobosco.

The Sentences of Sextus consisted of 451 sayings or principles, such as injunctions to love the truth, to avoid the pollution of the body with pleasure, to shun flatterers and to let one's tongue be harnessed by one's mind.

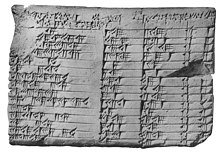

However, the primary interest of Islamic arithmeticians was in solving practical problems, such as taxation, measurement, the estimation of agricultural values and business applications for the buying and selling of goods.

[85] In the early 6th century the Roman philosopher Boethius popularised Pythagorean and Platonic conceptions of the universe and expounded the supreme importance of numerical ratios.

[86] The 7th century Bishop Isidore of Seville expressed his preference for the Pythagorean vision of a universe governed by the mystical properties of certain numbers, over the newly emerging Euclidean notion that knowledge could be built through deductive proofs.

[73] The 12th century theologian Hugh of Saint Victor found Pythagorean numerology so alluring that he set out to explain the human body entirely in numbers.

The Christian scholar Albertus Magnus rebuked the preoccupation with Pythagorean numerology, arguing that nature could not only be explained in terms of numbers.

[88] in Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir Al-Farabi rejected the notion of celestial harmony on the grounds that it was "plainly wrong" and that it was not possible for the heavens, orbs and stars to emit sounds through their motions.

In the 12th century the study of Plato gave rise to a vast body of literature explicating the glory of God as it reflected in the orderliness of the universe.

Writers such as Thierry of Chartres, William of Conches and Alexander Neckham referenced not only Plato but also other classical authors that had discussed Pythagoreanism, including Cicero, Ovid and Pliny.

[91] Many of the most eminent 17th century natural philosophers in Europe, including Francis Bacon, Descartes, Beeckman, Kepler, Mersenne, Stevin and Galileo, had a keen interest in music and acoustics.

Twenty-one centuries after Pythagoreas had taught his disciples in Italy, Galileo announced to the world that "the great book of nature" could only be read by those who understood the language of mathematics.