Quantum dot

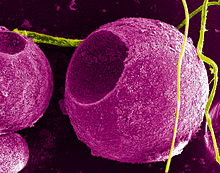

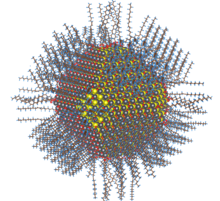

Quantum dots are usually coated with organic capping ligands (typically with long hydrocarbon chains, such as oleic acid) to control growth, prevent aggregation, and to promote dispersion in solution.

[23] For all of these core/shell systems, the deposition of the outer layer can lead to potential lattice mismatch, which can limit the ability to grow a thick shell without reducing photoluminescent performance.

To study the double-shell system, after synthesis of the core CdSe nanocrystals, a layer of ZnSe was coated prior to the ZnS outer shell, leading to an improvement in fluorescent efficiency by 70%.

Quantum dots defined by lithographically patterned gate electrodes, or by etching on two-dimensional electron gases in semiconductor heterostructures can have lateral dimensions between 20 and 100 nm.

Consequently, the specific recognition properties of the virus can be used to organize inorganic nanocrystals, forming ordered arrays over the length scale defined by liquid crystal formation.

Using this information, Lee et al. (2000)[citation needed] were able to create self-assembled, highly oriented, self-supporting films from a phage and ZnS precursor solution.

The process utilises identical molecules of a molecular cluster compound as the nucleation sites for nanoparticle growth, thus avoiding the need for a high temperature injection step.

Another approach for the mass production of colloidal quantum dots can be seen in the transfer of the well-known hot-injection methodology for the synthesis to a technical continuous flow system.

The batch-to-batch variations arising from the needs during the mentioned methodology can be overcome by utilizing technical components for mixing and growth as well as transport and temperature adjustments.

[48] In 2011 a consortium of U.S. and Dutch companies reported a milestone in high-volume quantum dot manufacturing by applying the traditional high temperature dual injection method to a flow system.

[49] On 23 January 2013 Dow entered into an exclusive licensing agreement with UK-based Nanoco for the use of their low-temperature molecular seeding method for bulk manufacture of cadmium-free quantum dots for electronic displays, and on 24 September 2014 Dow commenced work on the production facility in South Korea capable of producing sufficient quantum dots for "millions of cadmium-free televisions and other devices, such as tablets".

[52][53][54] Notably, the studies on quantum dot toxicity have focused on particles containing cadmium and have yet to be demonstrated in animal models after physiologically relevant dosing.

Assessing their potential toxicity is complex as these factors include properties such as QD size, charge, concentration, chemical composition, capping ligands, and also on their oxidative, mechanical, and photolytic stability.

It has been demonstrated that after exposure to ultraviolet radiation or oxidation by air, CdSe QDs release free cadmium ions causing cell death.

[55] Group II–VI QDs also have been reported to induce the formation of reactive oxygen species after exposure to light, which in turn can damage cellular components such as proteins, lipids, and DNA.

A recent novelty in the field is the discovery of carbon quantum dots, a new generation of optically active nanoparticles potentially capable of replacing semiconductor QDs, but with the advantage of much lower toxicity.

The new generations of quantum dots have far-reaching potential for the study of intracellular processes at the single-molecule level, high-resolution cellular imaging, long-term in vivo observation of cell trafficking, tumor targeting, and diagnostics.

[78] Another application that takes advantage of the extraordinary photostability of quantum dot probes is the real-time tracking of molecules and cells over extended periods of time.

[79] Antibodies, streptavidin,[80] peptides,[81] DNA,[82] nucleic acid aptamers,[83] or small-molecule ligands[84] can be used to target quantum dots to specific proteins on cells.

The ability to image single-cell migration in real time is expected to be important to several research areas such as embryogenesis, cancer metastasis, stem cell therapeutics, and lymphocyte immunology.

Moreover, it has shown that individual quantum dots delivered by this approach are detectable in the cell cytosol, thus illustrating the potential of this technique for single-molecule tracking studies.

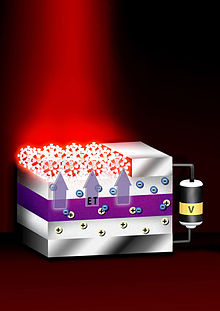

On the other hand, the quantum-confined ground-states of colloidal quantum dots (such as lead sulfide, PbS) incorporated in wider-bandgap host semiconductors (such as perovskite) can allow the generation of photocurrent from photons with energy below the host bandgap, via a two-photon absorption process, offering another approach (termed intermediate band, IB) to exploit a broader range of the solar spectrum and thereby achieve higher photovoltaic efficiency.

[98] Another potential use involves capped single-crystal ZnO nanowires with CdSe quantum dots, immersed in mercaptopropionic acid as hole transport medium in order to obtain a QD-sensitized solar cell.

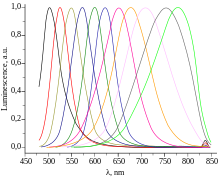

[106] In June 2006, QD Vision announced technical success in making a proof-of-concept quantum dot display and show a bright emission in the visible and near infrared region of the spectrum.

Such colloidal QDPs have potential applications in visible- and infrared-light cameras,[110] machine vision, industrial inspection, spectroscopy, and fluorescent biomedical imaging.

In photocatalysis, electron hole pairs formed in the dot under band gap excitation drive redox reactions in the surrounding liquid.

[112] Precise assembly of quantum dots can form superlattices that act as artificial solid-state materials that exhibit unique optical and electronic properties.

[128][129] Herbert Fröhlich in the 1930s first explored the idea that material properties can depend on the macroscopic dimensions of a small particle due to quantum size effects.

[130] The first quantum dots were synthesized in a glass matrix by Alexei A. Onushchenko and Alexey Ekimov in 1981 at the Vavilov State Optical Institute[131][132][133][134] and independently in colloidal suspension[135] by Louis E. Brus team at Bell Labs in 1983.

[140] In 1993, David J. Norris, Christopher B. Murray and Moungi Bawendi at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology reported on a hot-injection synthesis method for producing reproducible quantum dots with well-defined size and with high optical quality.