Radian

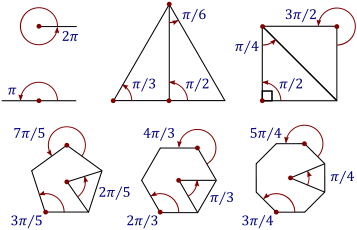

It is defined such that one radian is the angle subtended at the centre of a circle by an arc that is equal in length to the radius.

[4] Angles without explicitly specified units are generally assumed to be measured in radians, especially in mathematical writing.

[6] More generally, the magnitude in radians of a subtended angle is equal to the ratio of the arc length to the radius of the circle; that is,

[7] One complete revolution, expressed as an angle in radians, is the length of the circumference divided by the radius, which is

Since radian is the measure of an angle that is subtended by an arc of a length equal to the radius of the circle,

[4][12] Giacomo Prando writes "the current state of affairs leads inevitably to ghostly appearances and disappearances of the radian in the dimensional analysis of physical equations".

The first option changes the unit of a radius to meters per radian, but this is incompatible with dimensional analysis for the area of a circle, πr2.

According to Quincey this approach is "logically rigorous" compared to SI, but requires "the modification of many familiar mathematical and physical equations".

[20][24] Current SI can be considered relative to this framework as a natural unit system where the equation η = 1 is assumed to hold, or similarly, 1 rad = 1.

[25] Defining radian as a base unit may be useful for software, where the disadvantage of longer equations is minimal.

This is because radians have a mathematical naturalness that leads to a more elegant formulation of some important results.

For example, the use of radians leads to the simple limit formula which is the basis of many other identities in mathematics, including Because of these and other properties, the trigonometric functions appear in solutions to mathematical problems that are not obviously related to the functions' geometrical meanings (for example, the solutions to the differential equation

More generally, in complex-number theory, the arguments of these functions are (dimensionless, possibly complex) numbers—without any reference to physical angles at all.

Likewise, the phase angle difference of two waves can also be expressed using the radian as the unit.

This unit of angular measurement of a circle is in common use by telescopic sight manufacturers using (stadiametric) rangefinding in reticles.

The angular mil is an approximation of the milliradian used by NATO and other military organizations in gunnery and targeting.

Being based on the milliradian, the NATO mil subtends roughly 1 m at a range of 1000 m (at such small angles, the curvature is negligible).

[30] Newton in 1672 spoke of "the angular quantity of a body's circular motion", but used it only as a relative measure to develop an astronomical algorithm.

By 1722, his cousin Robert Smith had collected and published Cotes' mathematical writings in a book, Harmonia mensurarum.

[32] In a chapter of editorial comments, Smith gave what is probably the first published calculation of one radian in degrees, citing a note of Cotes that has not survived.

Smith described the radian in everything but name – "Now this number is equal to 180 degrees as the radius of a circle to the semicircumference, this is as 1 to 3.141592653589" –, and recognized its naturalness as a unit of angular measure.

[25] Prior to the term radian becoming widespread, the unit was commonly called circular measure of an angle.

[36] The term radian first appeared in print on 5 June 1873, in examination questions set by James Thomson (brother of Lord Kelvin) at Queen's College, Belfast.

Longmans' School Trigonometry still called the radian circular measure when published in 1890.

Macfarlane reached this idea or ratios of areas while considering the basis for hyperbolic angle which is analogously defined.

[42] As Paul Quincey et al. write, "the status of angles within the International System of Units (SI) has long been a source of controversy and confusion.

"[43] In 1960, the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) established the SI and the radian was classified as a "supplementary unit" along with the steradian.

[44] Richard Nelson writes "This ambiguity [in the classification of the supplemental units] prompted a spirited discussion over their proper interpretation.

A small number of members argued strongly that the radian should be a base unit, but the majority felt the status quo was acceptable or that the change would cause more problems than it would solve.

A task group was established to "review the historical use of SI supplementary units and consider whether reintroduction would be of benefit", among other activities.