Rationalism

On the one hand, rationalists like René Descartes emphasized that knowledge is primarily innate and the intellect, the inner faculty of the human mind, can therefore directly grasp or derive logical truths; on the other hand, empiricists like John Locke emphasized that knowledge is not primarily innate and is best gained by careful observation of the physical world outside the mind, namely through sensory experiences.

Rationalists asserted that certain principles exist in logic, mathematics, ethics, and metaphysics that are so fundamentally true that denying them causes one to fall into contradiction.

The rationalists had such a high confidence in reason that empirical proof and physical evidence were regarded as unnecessary to ascertain certain truths – in other words, "there are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense experience".

[2] Given a pre-modern understanding of reason, rationalism is identical to philosophy, the Socratic life of inquiry, or the zetetic (skeptical) clear interpretation of authority (open to the underlying or essential cause of things as they appear to our sense of certainty).

Also, the distinction between the two philosophies is not as clear-cut as is sometimes suggested; for example, Descartes and Locke have similar views about the nature of human ideas.

[5] Proponents of some varieties of rationalism argue that, starting with foundational basic principles, like the axioms of geometry, one could deductively derive the rest of all possible knowledge.

Notable philosophers who held this view most clearly were Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, whose attempts to grapple with the epistemological and metaphysical problems raised by Descartes led to a development of the fundamental approach of rationalism.

[8][9] In this regard, the philosopher John Cottingham[10] noted how rationalism, a methodology, became socially conflated with atheism, a worldview: In the past, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, the term 'rationalist' was often used to refer to free thinkers of an anti-clerical and anti-religious outlook, and for a time the word acquired a distinctly pejorative force (thus in 1670 Sanderson spoke disparagingly of 'a mere rationalist, that is to say in plain English an atheist of the late edition...').

[11][2] Taken to extremes, the empiricist view holds that all ideas come to us a posteriori, that is to say, through experience; either through the external senses or through such inner sensations as pain and gratification.

"[12] Between both philosophies, the issue at hand is the fundamental source of human knowledge and the proper techniques for verifying what we think we know.

Epistemologists are concerned with various epistemic features of belief, which include the ideas of justification, warrant, rationality, and probability.

Much of the debate in these fields are focused on analyzing the nature of knowledge and how it relates to connected notions such as truth, belief, and justification.

"[13]Generally speaking, intuition is a priori knowledge or experiential belief characterized by its immediacy; a form of rational insight.

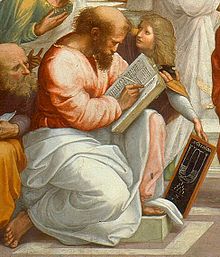

[22] He is often revered as a great mathematician, mystic and scientist, but he is best known for the Pythagorean theorem, which bears his name, and for discovering the mathematical relationship between the length of strings on lute and the pitches of the notes.

[32] Although the three great Greek philosophers disagreed with one another on specific points, they all agreed that rational thought could bring to light knowledge that was self-evident – information that humans otherwise could not know without the use of reason.

[33] One notable event in the Western timeline was the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas who attempted to merge Greek rationalism and Christian revelation in the thirteenth-century.

[23][34] Generally, the Roman Catholic Church viewed Rationalists as a threat, labeling them as those who "while admitting revelation, reject from the word of God whatever, in their private judgment, is inconsistent with human reason.

For instance, his famous dictum, cogito ergo sum or "I think, therefore I am", is a conclusion reached a priori i.e., prior to any kind of experience on the matter.

This crucial distinction would be left unresolved and lead to what is known as the mind–body problem, since the two substances in the Cartesian system are independent of each other and irreducible.

[39][40][41] Spinoza's philosophy is a system of ideas constructed upon basic building blocks with an internal consistency with which he tried to answer life's major questions and in which he proposed that "God exists only philosophically.

Many of Spinoza's ideas continue to vex thinkers today and many of his principles, particularly regarding the emotions, have implications for modern approaches to psychology.

[citation needed] His magnum opus, Ethics, contains unresolved obscurities and has a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry.

Leibniz developed his theory of monads in response to both Descartes and Spinoza, because the rejection of their visions forced him to arrive at his own solution.

These units of reality represent the universe, though they are not subject to the laws of causality or space (which he called "well-founded phenomena").

[51] Kant named his brand of epistemology "Transcendental Idealism", and he first laid out these views in his famous work The Critique of Pure Reason.

To the rationalists he argued, broadly, that pure reason is flawed when it goes beyond its limits and claims to know those things that are necessarily beyond the realm of every possible experience: the existence of God, free will, and the immortality of the human soul.

"In Kant's views, a priori concepts do exist, but if they are to lead to the amplification of knowledge, they must be brought into relation with empirical data".

For example, Robert Brandom has appropriated the terms "rationalist expressivism" and "rationalist pragmatism" as labels for aspects of his programme in Articulating Reasons, and identified "linguistic rationalism", the claim that the contents of propositions "are essentially what can serve as both premises and conclusions of inferences", as a key thesis of Wilfred Sellars.

However, cumulative research in neuroscience suggests that only a small part of the brain's activities operate at the level of conscious reflection.

Emotions are inextricably intertwined with people's social norms and identities, which are typically outside the scope of standard rationalist accounts.